by Mark Harvey

Mark Twain’s two rules for investing: 1) Don’t invest when you can’t afford to. 2) Don’t invest when you can.

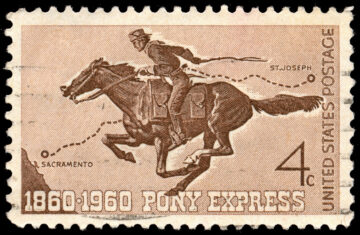

Hemorrhaging money and high burn rates on startups is not something new in American culture. We’ve been doing it for a couple hundred years. Take the pony express, for example. That celebrated mail delivery company–a huge part of western lore–only lasted about eighteen months. The idea was to deliver mail across the western side of the US from Missouri to California, where there was still no contiguous telegraph connection or railway connection. In some ways the pony express was a huge success, even if in only showing the vast amount of country wee brave men could cover on a horse in a short amount of time. I say wee because pony express riders were required to weigh less than 125 pounds, kind of like modern jockeys.

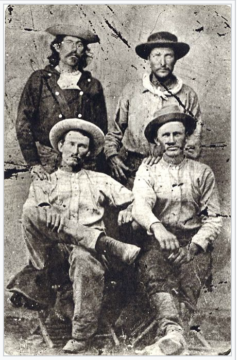

In just a few months, three business partners, William Russell, Alexander Majors, and Wiliam Waddell, established 184 stations, purchased about 400 horses, hired 80 riders, and set the thing into motion. On April 3, 1860, the first express rider left St. Joseph Missouri with a mail pouch containing 50 letters and five telegrams. Ten days later, the letters arrived in Sacramento, some 1,900 miles away. The express riders must have been ridiculously tough men, covering up to 100 miles in single rides using multiple horses staged along the route. Anyone who’s ever ridden just 30 miles in a day knows how tired it makes a person.

But the company didn’t last. For one thing, the continental-length telegraph system was completed in October of 1861 when the two major telegraph companies, the Overland and the Pacific, joined lines in Salt Lake City. You’d think that the messieurs who started the pony express and who were otherwise very successful businessmen would have seen this disruptive technology on the horizon. Maybe they did and they just wanted to open what was maybe the coolest startup on the face of the earth, even if it only lasted a year and a half.

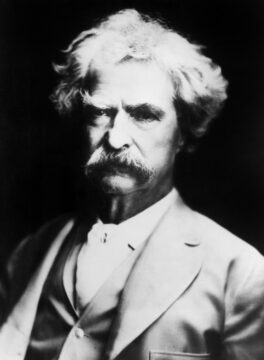

Describing the Pony Express riders in his book Roughing It, Mark Twain wrote,

He rode a splendid horse that was born for a racer and fed and lodged like a gentleman; kept him at his utmost speed for ten miles, and then, as he came crashing up to the station where stood two men holding fast a fresh, impatient steed, the transfer of rider and mail-bag was made in the twinkling of an eye, and away flew the eager pair and were out of sight before the spectator could get hardly the ghost of a look.

Pony Express riders were required to take quite a serious oath “before the Great and Living God” not to drink, use profane language, quarrel or fight with other employees. Supposedly the ads soliciting riders read, “Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred.” True or not, that would have been the ideal employee.

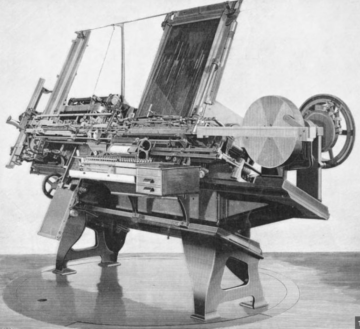

Years after the Pony Express went bankrupt, Mark Twain lost his entire fortune and his wife’s inheritance, too, when he invested in a contraption called the Paige Compositor, invented by James W Paige. The Compositor was meant to revolutionize printing by allowing typesetters to set type five or six times faster than what was possible in traditional machines. It was a good idea because the slow typesetting process was the bottleneck for newspapers across the world. Even as printing presses became steam powered and very fast, the typesetting was dreadfully slow—about a 100 words per hour.

Paige began developing the machine in about 1870 and made real progress. The machine eventually encompassed around 18,000 parts and could really lay out type about five times faster than the old contraptions. But it was a quirky, unreliable machine. Twain, a publisher himself, met Paige in 1880 and was spellbound by the invention and by Paige the man. Describing the inventor, Twain wrote, “[He] could persuade a fish to come out and take a walk with him. When he is present I always believe him; I can’t help it.”

Twain began to pour huge amounts of money into the development of the Compositor—about $7,000 per month (today’s equivalent of close to $200,000). Unfortunately, an equally gifted inventor came up with the linotype (short for line-of-type) machine and brought it to the market in 1886. The linotype turned out to be practical, reliable, and fast. It helped put Paige and the Compositor out of business and bankrupted poor Twain.

If you’re going to burn a lot of capital into thin air, you may as well burn it on a raging relay race of galloping horses crossing deserts, mountains, and Indian country, or on an effort to revolutionize printing rather than shipping discounted kitty litter like the legendary failure Pets.Com. Pets.Com, launched in 1998, closed after only two years in business. It only lasted about six months longer than the pony express.

There were a few things wrong with the Pets.Com business model. First, it was selling some of its products for about a third of the price it was paying its suppliers. Second, the profit margins in the dog-eat-dog pet products industry are traditionally only about two to four percent. Third, shipping bulky, heavy, low-margin items like dog food and kitty litter is expensive.

Despite a dubious business model, the company went public in 2000 and at eleven dollars per share was valued at close to $300 million. Nine months later, the business was closed down and its liquidation value was around $125,000. After the liquidation, investors were paid nine cents per share. Those who bought shares at eleven dollars on the initial public offering lost 99% of their investment.

To be fair, the online sales of pet-related products nowadays is in the billions and some say Pets.Com was a good idea launched before its time. Nevertheless, the money lost on the Pets.Com business—and the speed at which that money was lost—is breathtaking.

I’ve made some money-losing investments in startups myself. They’re only boneheaded in retrospect because at the time they seemed like good business plans and the people selling me the ideas had the same persuasive qualities that James Paige had on Mark Twain—they could convince a fish to walk ashore.

I invested in a company that was meant to shred old tires and then break the composite tire materials into component parts that could be sold on the broader market. The biggest and most valuable component from used tires is something called carbon black, which is worth billions of dollars worldwide and is used in all sorts of industrial applications. It’s used in toner ink, to dye plastics, making electric cables, making batteries, and…in making new tires.

Getting old used tires is very cheap. There are billions of them scattered around the world and some countries just want to get rid of them. The attractive element of the company I invested in was a proprietary method of finely milling the tires and then breaking them down with pyrolysis. Things started off well with the processing, finding customers, and then selling the carbon black. But as with many startups there were some unanticipated events—closed plants, permitting problems, etc.—that eventually killed the company.

Getting old used tires is very cheap. There are billions of them scattered around the world and some countries just want to get rid of them. The attractive element of the company I invested in was a proprietary method of finely milling the tires and then breaking them down with pyrolysis. Things started off well with the processing, finding customers, and then selling the carbon black. But as with many startups there were some unanticipated events—closed plants, permitting problems, etc.—that eventually killed the company.

But like Pets.Com, the company I invested in may have just been a little ahead of its time. In 2020, several huge multinational companies such as Michelin, Orion, and Quantis formed a consortium called BlackCycle. Its charter reads,

Officially launched in May 2020, the BlackCycle project aims to enable a massive circular economy of tyres. This European project funded by Horizon 2020 will design world-first processes to make new tyres from end-of-life tyres.

One of the main technologies BlackCycle is working on is pyrolysis. Darn!

Most investors would do best by buying the most boring composite funds made up of an even mix of all the companies on the Standard & Poors 500 index. Such composites are called Exchange-Traded Funds and unless you are a very gifted and very dedicated investor, these ETFs will almost always make you more money than if you’re a market-timing stock picker or taking chances on new startups. Actually, the ETFs beat most of the self-proclaimed “pros” and there are minimal fees associated with them.

But we might not have much to buy outside of soap and toothpaste if there were none of the swing-for-the-fences entrepreneurs and venture capitalists. There would be no Google, Apple, or Fedex without the crazy risk takers. And even if you’re not wild about those companies, there would be no Sierra Nevada Craft Beer, Chobani Yogurt, or the world-class wind turbines without people willing to go out on the bleeding edge with their finances. Without the risk takers we’d be printing 3Quarks Magazine on a Gutenberg.

Raw capitalism has plenty of shortcomings—including newly minted billionaires preening around the world on their ridiculously lavish yachts. But the countries that tried heavily regulated communism managed to crush innovation. As someone who grew up before the Berlin Wall came down, I don’t remember getting all tingly about the newest Soviet sports car. And not a lot of great computers came out of Novosibirsk.

So on we go with the singular American sport of taking huge risks on dubious ideas, some that will pan out, and some that will crash spectacularly. By the way, the term “pan out” comes from that oh-so-predictable livelihood of panning for gold. The guys and gals that take these ideas to crowning success develop cult followings and the ones who fail sometimes end up in jail or the poor house. Mark Twain was said to have lost his sense of humor when he lost his fortune.

It’s never pretty when the cash dries up and the ponies are sold, but ahh the glory of those wild rides to Sacramento!