by David J. Lobina

It was no accident that it was an immigrant who revived the debate. While Marxist thought provided (…) a lens through which to observe the nation from the outside, the experience of living as an “alien” (…) proved an almost indispensable condition for (…) more advanced tools of observation.

—Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People.

Who he? Exactly.

An “anarchist rabbi” nowadays mostly known for a book on Anarcho-Syndicalism as well as for his involvement with the Jewish anarchist movement in East London at the turn of the 20th century, the life and work of the German thinker Rudolf Rocker has much to teach us in these most modern of times, if only we were to read him more often. Of particular interest to me is his magnum opus, Nationalism and Culture, a work now basically forgotten but which was regarded as a genuine contribution to the study of nationalism (and other topics) when it was published in 1937 by people as diverse as Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, and Herbert Read. The book, and Rocker himself, are now due a revisit.[i]

The first thing one notes when approaching Nationalism and Culture is its impressive combination of breadth and depth. The book covers multiple time periods, thinkers, and artistic developments, and in doing so Rocker chronicles how the state and the nationalist worldview have combined to shape the contemporary world, influencing life and manners, thought and culture, and much else – and for this alone it should be more widely known.[ii]

But I’m getting ahead of myself. As is often the case, Rocker’s outlook was partly a product of the times he lived, so let’s start with that first and I will come back to the book next month.

Rocker left a large bibliography behind, including about his own experiences, and while many biographical details have been accounted for (for instance, here and here), the record is necessarily an incomplete one. Rocker wrote three volumes of memoirs, only a small part of which has been published in English, and conducted a large correspondence, much of which remains unpublished to this day (for a time he also kept a diary; most of Rocker’s personal papers are at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, where they were donated by his second son in 1960). I will base my brief biographical sketch on some of these sources.

Born to working class parents in 1873 in Mainz, Rocker’s aversion to any form of authoritarianism and institutionalism, a hallmark of anarchist thought, appears to have formed very early on. Mainz itself provided an amenable climate for radical politics; the city had been mostly autonomous during the 18th century as part of the French Republic and its citizens had in fact objected to becoming part of the German Empire upon the unification of Germany in 1871. The anti-Prussian sentiment was certainly present in Rocker’s family, and a politically active uncle was to be a particularly important influence in his life.

Already finding the strictures of school too rigid as a young boy, these feelings were compounded during his time at the catholic orphanage he was sent to soon after his mother’s passing in 1887 (his father had died in 1877). After leaving school, he learned bookbinding and became politically engaged, joining his uncle’s Social Democratic Party in 1890, though he would soon get involved with an internal faction which espoused more radical politics (the so-called Jungen youth group). By the time Rocker attended the Congress of the Second International in Brussels in August 1891, he had become an anarchist and by October had been expelled from the SDP. Rocker’s distrust of state-directed socialism and his preference for a libertarian kind associated to the syndicalist movement would be a constant in his life.

Rocker’s activities eventually came to the attention of the authorities – some of Germany’s anti-socialist laws had ended in 1890, but police repression continued – and after becoming involved in illegal propaganda he fled to Paris in 1892 (he was also keen to avoid conscription at age 20, which was compulsory). His first political exile had begun and would last over 25 years. It was in Paris where Rocker first encountered Jewish anarchists, and by the time he moved to London in 1895, he would soon gravitate towards London’s East End, where most Jewish immigrants had settled. Rocker’s time in London is possibly the most interesting part of his life, as it constitutes a fascinating story of how a German Catholic became a leading figure in London’s Yiddish-speaking Jewish anarchist movement – it is certainly the better known of Rocker’s lifelong activism.[iii]

By the 19th century, England had become the home of many left-wing political exiles fleeing more autocratic regimes in continental Europe. Widely regarded as a safe haven because of the Victorian “right of asylum”, which would be curtailed in the early 20th century, England had welcomed the repressed as well, such as the many Jews who fled Russia during the pogroms of 1881-1884.[iv] Socialist groups had of course been common in England since the mid 19th century, but by the end of the century there were also specifically Jewish socialist groups. Rocker credits Aaron Liebermann as a pioneer of the Jewish labour movement, and it was indeed Liebermann who had founded a union of Jewish socialists in London in 1876, the first of its kind – Agudas HaSozialistim HoIvrim, or the Hebrew Socialist Union.

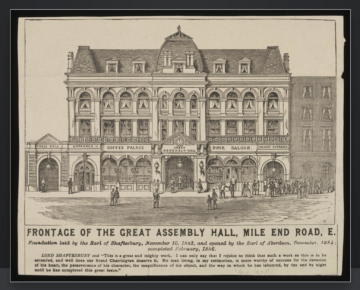

As mentioned, most Jewish immigrants concentrated on London’s East End, a poor and heavily populated district; historians estimate that there were around 120,000 Jews residents at the time (contemporary photographic record of the area is still available). A world Rocker would join fully, he started attending the meetings of various Jewish radical groups and was soon busy organising numerous meetings and talks, including at well-known venues such as the Great Assembly Hall and the Wonderland, where he would speak himself. More importantly, and certainly more enduring, were Rocker’s endeavours at the Jubilee Street Club. Founded by Rocker and fellow Jewish anarchists, Rocker’s activities there is what he was most fondly remembered for by the community, as recorded in various oral accounts of the times.

The Club started in 1906 and was open to everyone, offering its users a library and reading rooms as well as various educational programmes. Courses in English were the most popular, as many Jews in the East End didn’t speak the language and had little contact with the local population (Rocker himself lectured in history and sociology).

Rocker’s immersion in the Jewish community was to be very comprehensive. He moved to the East End and at a political event met the person who would become his lifelong companion – Milly Witkop, an activist from a very religious Jewish family from Ukraine who had also made use of the Victorian right of asylum, eventually bringing her family over to London (Milly’s anarchism as well as her partnership with Rocker would, however, estrange her from her family for a time). They had a son in 1907, Rocker’s second, and lived in the area until they left London for good in 1918 (their son Fermin has left an interview and a memoir of their time in London).

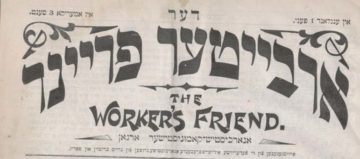

Rocker did an enormous amount of writing and editing during this time, and at one point he was even offered the position of editor at a small Yiddish-language periodical, a language he didn’t speak but had encountered in Paris, which he had then regarded a dialect of German (Yiddish was closer to German at the time than is the case today). He gradually learned Yiddish and in 1889 was asked to run Der Arbeter Fraynd (The Worker’s Friend), a better-known Yiddish periodical. Rocker would devote himself to both the Arbeter Fraynd and the activities of the Jubilee Street Club in the following years. He even started his own magazine during this time – Germinal – which Rocker edited and typeset in his own home (with Milly’s help).

These periodicals were instrumental for the activism Rocker and colleagues conducted at the time, not least to organise industrial action for better pay and conditions, a perennial issue in the sweatshops of East London. Charles Booth’s 1902 classic in social research, Life and Labour of the People of London, had indeed described the tailoring industry as being infected by ‘a sweating disease’ where low wages, long hours, and unsanitary conditions prevailed, and this is precisely where many Jews from the East End worked.

One result of this was the 1912 Tailors’ Strike, which started in west London and soon spread to the east with Rocker’s active participation. There was also a strike by the London dockers at around the same time, and this series of events eventually saw thousands of people strike and some genuine victories won. It was an occasion for Jewish and English workers to collaborate as well, though this did not happen as often as Rocker would have liked. There was an element of xenophobia towards immigrants in London at the time and the Jew was then viewed as the archetypical foreigner, an undercurrent Rocker would experience himself as a German when the First World War broke out.

It all came to an end with the advent of the Great War and Rocker’s interment as an enemy alien in late 1914, where he would remain until he was released in 1918. He was taken to various camps, most notably the Alexandra Palace in North London, where his firstborn, Rudolf Jr, would eventually join him too. The Alexandra Palace camp was organised as a military camp, and this proved a heavy burden for the interred, the majority of whom were civilians. Some pictures from the time provide an idea of the conditions the interred faced and there are also reports of what daily life was like (this BBC clip discusses internment at the Palace and briefly mentions Rocker).

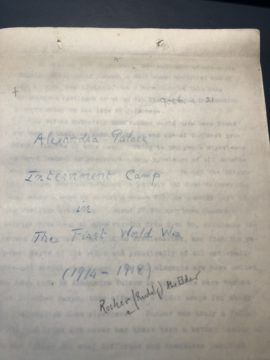

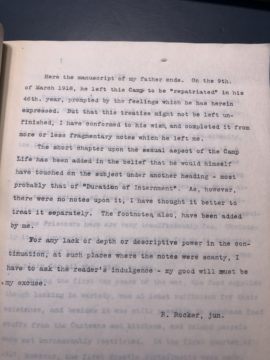

Rocker’s skills and experience would come in handy in this new environment. He became leader of a “battalion” and in that capacity was able to negotiate better conditions for the interred. Rocker even managed to organise educational programmes and found himself teaching and lecturing again. He wrote much in the camp too, especially diaries and correspondence, but also an interesting essay on “camp psychology” detailing, among other things, the mental toll of being interred for the sole reason of being German – one particular point Rocker makes in this essay is the fact that many of his co-nationals became more militaristic and patriotic than they would have been had they not been interred in the first place (the British Library in London holds a typescript, as shown in the photo below, which Rocker never actually finished).

In 1916, Milly was herself arrested. Russians had been ordered to enlist or face deportation during the war and as a nominally Russian citizen she helped organise a series of protests against the policy. She was held at a women’s prison and was released towards the end of the war (Fermin was placed under the care of relatives and friends).

Once hostilities had ceased, it was decided that most German citizens would be deported to Germany. Rocker was sent to the Netherlands in March 1918 in order to be repatriated to Germany, but in the event he was denied entry at the border because his German citizenship had lapsed, forcing him to stay in the Netherlands as a stateless refugee. He was reunited with Milly there, and after the German revolution of 1918-19, the whole family was able to make their way to what was now the Weimar Republic of Germany.

It was back in Germany, in the 1920s, when Rocker started working on Nationalism and Culture, which he initially envisioned as a short book but would only finish in the 1930s – by then Rocker and his family had fled Nazi Germany, arriving in New York in 1933, Rocker’s second and last exile (he died in the US in 1955). The book was first published in Spanish in 1937 and in English soon after, and together with Anarcho-Syndicalism, remains the prime example of Rocker’s mature thought, though these are but the tip of the literary iceberg he left behind. Untranslated and so far unavailable are the hundreds of pages he wrote in the Yiddish periodicals he edited in London, a significant and so far lost record of the pre-war years the poorer Jewish working classes experienced – and of Rocker’s life and thought.

Going back to Nationalism and Culture, and as alluded to at the beginning, this is a very ambitious and interesting book. Not only an impressive piece of scholarship, it is also a tour de force defence of Rocker’s political and ideological ideas. Thus, we find Rocker’s insistence on the importance of personal freedom and his concern regarding society’s ability to protect this freedom by non-coercive means; his rejection of all forms of authority and most kinds of organisation, except worker’s unions and some others; his rejection of the private property of the means of production; and, last but not least, his belief that a socialist order of things constitutes the best way to safeguard free societies.

Sounds interesting? I shall come back to this in four weeks!

[i] Rocker’s epithet as an “anarchist rabbi” is the title of both a book and a documentary about Rocker: Mina Graur, An “Anarchist Rabbi” (PhD thesis, 1988; published as a book by St Martin’s Press, NY, in 1998), and Adam Kossoff, The Anarchist Rabbi (Documentary film, 2014). Some of the popularity of Rocker’s Anarcho-Syndicalism book, published in 1938, may have something to do with Noam Chomsky’s championing of it over the years – the modern edition includes a short preface by Chomsky, for instance (curiously, my own copy of Anarcho-Syndicalism, which I found in a second-hand bookshop in London a long time ago, is signed by Chomsky himself). The quote heading this post, which comes from Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People (London, England: Verso, 2009, p. 34), refers to Karl Deutsch, a political scientist who emigrated from his native Czechoslovakia during the Nazi occupation of 1939-45, but it applies to Rocker rather well too. A focal point of Sand’s book is the contribution of converts to Judaism to a Jewish/Israeli national identity, and though Rocker was neither such a convert nor did he seek to promote any national feelings, he was a kind of Gentile-Jew interloper, foreign to both peoples. As we shall see, this will be a theme of this two-parter.

[ii] Chomsky, again, is an exception; he has discussed Rocker’s 1937 book in various places, for instance in his Chomsky on Anarchism (Edinburgh, Scotland: AK Press, 2005, chapter 2). My own series on Language and Nationalism here at 3QD was greatly influenced by Rocker’s Nationalism and Culture, and those posts are, in a way, an update of the book, though not explicitly so.

[iii] This is possibly because the English version of the memoirs is the only easily available volume of the memoirs these days, and these only cover Rocker’s time in London. I should add a couple of comments on the memoirs, in fact, as there is some confusion about them, especially in online anarchist forums and among the editors of Rocker’s entry on Wikipedia (ah, the battles I fight sometimes!). Rocker’s memoirs were originally written in German and have only been published in full in Spanish in the 1940-50s and in Yiddish in the 1950-60s, some of these books released in Argentina but now long out of print, with the noted Spanish anarchist Diego Abad de Santillán as the translator of the Spanish versions (a German edition from 1974 only offers a selection from the original typescripts). As mentioned, the English version covers Rocker’s time in London, to which Rocker devoted the second volume of the memoirs, and was first published in 1956, possibly as a translation of the corresponding Yiddish volume from 1952. This edition, however, which was titled The London Years, in contrast to the curious Sturm und Drang of the original (which was rendered as In the storm: Years of Exile in the Spanish and Yiddish versions, losing the reference to the artistic movement), is not a translation of the entire second volume of Rocker’s memoirs, but of only a part of it. Though this aspect of the translation goes unmentioned in the introduction provided by the translator, one Joseph Leftwich (born Lefkowitz), a note on the dedication page explicitly states that the book is an abridgement of Rocker’s memoirs (see the photos below); a comparison of this edition with the Spanish translation of the second volume, which I have carried out myself, clearly shows that the English version is much shorter than the second volume (curiously, the first chapter of The London Years is an abridged version of one of the last chapters of the first volume of the memoirs, which in the original functions as a conduit to the second volume and here seems to have been added as a way to provide some sort of unity to the book, which was meant as a single, standalone volume). Complicating matters somewhat is the fact that the English edition of 1956 was re-edited in 2005 with a new typeset, thus reducing the number of pages significantly, from over 350 pages to a little over 200, but this is simply a reflection of employing a more modern (and smaller) typeface and spacing, as the actual text itself remains basically the same, as I have been able to ascertain myself here too (the 2005 edition also contains ‘the abridgement note’, in this case tucked away in the copyright page, though the translator’s introduction is not included). It has to be said, in any case, that Rocker’s full memoirs, which I have read in Spanish, don’t contain as much information about his life as one may expect (the mother of his first child is not even dignified with a name, and is simply referred to as ‘a girl’). The memoirs are more of a commentary of the times, in fact, and though this makes them fascinating in their own right, there is endless details about the politics of the day.

[iv] For a thorough account of how the Rocker-Wiktop family was affected by Britain’s “right of asylum”, including its eventual curtailment, see Thomas C. Jones, “The Rocker-Wiktop family and the closing of political asylum in Britain”, Revue d’histoire du XIX siècle, 61, 123-149.