by Gus Mitchell

Everything is content and content is everything. An uncountable noun, like information, content has a monolithic singularity to it. A meme, tweet, image, targeted ad; a song, podcast, TV show or movie on a streaming platform; an explainer, a reaction; clickbait articles, legitimate journalism; bodycam footage of police taking down a gunman or a teenager; screenshots of appalling dating app interactions; an influencer retooling her school shooting trauma to sell Bioré skincare products on TikTok—it’s all content.

Of course, there are shades and varieties. Shareable content. Meme-able content. Viral content. Relatable content. Quality content. Exclusive and original content. Parasocial content: a conversational podcast, familiar voices filling up the dull silence of shopping, cooking, walking. Or ambient or second screen content, the actual content of which is negligible given that you’re probably consuming more content on another device at the same time.

What keeps us in this voracious state of content consumption? Decades ahead of his time, the late British spiritual writer and lecturer Alan Watts may have hit on an explanation. In a talk delivered in the late 1960s, he described the experience of flicking through Life Magazine as one of “pacified agitation.” Being in this state, he noted, leaves you with “a set of impressions” rather than giving you anything to “chew on.” It is this same agitation that keeps us coming back, consuming ever more content in search of some ever-elusive contentment. But it’s impossible to feel full when the internet’s capacity for containing, sharing, and proliferating its content is limitless. We cannot speak of the contents of the internet as we would once have named the contents of a book or a jar. The plural implies finitude, the singular a flatness, without depth or dimension.

A core capitalist imperative is manufacturing wants, then re-engineering those wants and the world around them so that they become needs. Existing needs must be maintained, and new ones found. One could look at the development of anything from the automobile to the cell phone through this lens, and the capitalist model of cultural consumption is no different––except, of course, that cultural production and consumption is less predictable, less quantifiable, than iPhones or BMWs. Culture and art entertain us, of course, but they can also promise (sometimes, at least) to feed the hunger for deeper meaning and feeling left by everyday life (especially under capitalism). But where culture and art once promised to feed this hunger, content feeds a void that only gapes wider the more we consume.

It’s not the hunger fulfilled or meaning found through experiencing art that content promises: indeed, it is not really the experience at all anymore. It is, rather, the promise of content’s constant and convenient availability that we have come to value, to depend on––and that also means, of course, the capitalist delivery system behind it. The flattening of culture into the streaming wash of content, then, safeguards another core capitalist ethos: everything is for sale.

Since the early days of the internet, content has been capitalism’s pinnacle commodity online. Publisher and editor John F. Oppedahl coined the term “content marketing” in 1996 while leading a roundtable at the American Society for Newspaper Editors. He was interested in how publications might better identify and anticipate—and, ultimately, decide—readers’ needs and wishes, cultivating a more sustainable customer base. Content marketing soon became a catchall for creating writing, images, and other media distinct from mere advertising but still calculated to generate revenue. As access to the web became widespread through the 1990s, and more people found it easier to become entrepreneurs, buyers, and sellers, content became common currency.

By 1998, Netscape had hired Jerrell Jimerson as its Director of Online and Content Marketing. The next year, author Jeff Cannon published a book entitled Make Your Website Work for You: How to Turn Online Content into Profits. Blogs, email, websites, and eventually social media facilitated content creation and dissemination at an unprecedented scale. As Cannon wrote: “Content is King.” With the surveillance infrastructure that was part of the internet even then, companies could also measure “engagement” in site traffic, page clicks, and emails opened, with great precision. In the years that followed, content would come to refer to just about everything we consume online. But as its origins indicate, consumption was always the point. The content of content is always, at its core, secondary.

With the advent of Web 2.0 came the monetization of that human urge to share, show off, and self-fashion by creating user-generated content. In the early 2000s, Google’s novel ad revenue model and the adoption of similar approaches by new social networks transformed social users into content creators, willing collaborators in contenting their own lives for the feed. Now, clicks meant cash for tech giants, and social content became a vehicle for selling ads. Combine the bottomless content capacity of the internet and the concomitant boundlessness of its main players’ profit motives, and we get today’s online experience, where platforms, apps, and their endless stream of undifferentiated content—amusing, innocuous, irrelevant, informative, disturbing—serve only one discontenting and absurdist end: keeping us latched to our devices.

It is fitting that “platform” was the name given to the depthless, ever-stretching spaces that hold content. Content exists to fill the platform, but the platform was not made to be filled. Crucial to the design of everything from TikTok to Netflix is that nothing impedes the smooth circulations of clicking, swiping, scrolling, engaging, consuming. In turn, the constant availability of content anywhere and everywhere fosters a passivity which negates digestion. Content is soothingly, but addictively integrated into quotidian existence, a reliable and serviceable need like any other. It is also the prime addiction of everyday life: addiction to inputs, the unceasing flow of information and entertainment, the line between the two ever hazier.

At the same time, the pacifying immateriality of our digitised culture agitates us. It’s uncomfortable to not be able to see, touch, or hold what we’re taking in, as if it was something which really had value, which really took time and work and love to make. The more we consume, the more anxiously we make lists, and hoard information, attempting to keep track of it all. Goodreads, Letterboxd, Spotify playlists, the swelling Notes app, throngs of open tabs—each of us is laboring over our own ever-incomplete Library of Babel. Our glut of content is so overabundant, so overwhelming, that sifting, sorting, and cataloging replace the joy of spontaneous affinity, of chancing upon something that wasn’t part of any list. When any song, article, or idea is just a tap away, it feels like it must be possible to locate exactly what one wants any time. In a café once I overheard some girls at the next table say (of Spotify): “I can’t just hear a song anymore –– it has to go somewhere!”

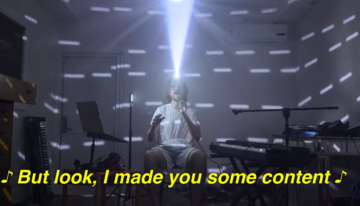

Artists—“creators”—were quick to recognize how the feedback loop of content consumption leaves everyone hungry. Bo Burnham began his 2021 Netflix special, Inside, with a song called “Content.” “But look, I made you some content!” the chorus goes. “Daddy made you your favorite, open wide: here comes the content!” Burnham understands himself, like us, to be a prisoner of the new streaming marketplace, where metrics are everything, the cultural web-scape and discourse is obliterated and replenished within days, and the audience—evermore distracted, bored, awash in content—is unable to play with a full attentional deck. It’s hardly coincidental that movies and art exhibits have started marketing themselves as “immersive experiences.”

At its best, the object of culture and art is inherently and functionally immersive. Great writers, say, or great orchestras, create a world: one that absorbs, immerses, completes us, satisfies us on its own terms, and returns us to the “real” world, more awake, perhaps, than we were before. If culture were about consuming, producing, and circulating as much and as quickly as possible then the best writer would be the one who writes the most books and the best orchestra the one that plays the fastest.

Art works at a different pace––or rather, for art to truly work on us at all requires a different conception of time and of its value. If we really do still wish to enter and feel immersed in the world of an artwork, changed by culture as a meaningful alternative to and a window on the everyday, then we must relinquish those twin impulses toward convenience and control that define everyday capitalist mentality. Both, after all, are consequences of that mantra, “time is money.” The reliable availability of “infinite content” has now become so seamlessly, soothingly integrated into our quotidian existence that culture––as delivered digitally, at least––is no longer serving this function as an escape, a window, a horizon of possible alternatives. It is becoming, instead, a kind of electronic wallpaper.

In the age of content then, harnessing that feeling might entail slowing down and embracing limits. “Content” – like a book or a jar’s contents – used to be something held together, contained, by a form. Consider the other meaning of the word; to feel “content” suggests a link between fullness and a sense of completion. We can never feel this contentment while we’re caught in a cycle of constant consumption, in which ephemeral, insubstantial and essentially valueless culture circulates in a frictionless digital space. Echoing the absurdity of a wider financialized economy, value is placed in (and accrues to) not art and the artists themselves, but to those mechanisms and people that circulate and commodify them. It is a cycle that, ultimately, benefits no-one but the owners of the platforms.

Resisting this suffocating cycle will mean once again learning, in more ways than one, how to value the labor of those by which meaningful art and culture are created and shared. Our culture should be our last, best haven from the discontented production-consumption cycles that otherwise define our time.

In 2014, the New York indie-punk band Parquet Courts released a song called “Content Nausea,” which issued a warning about an opaque, and newly ubiquitous word:

And am I under some spell?

And do my thoughts belong to me?

Or just some slogan I ingested to save time?

Overpopulated by nothing, crowded by a sparseness

Guided by darkness, too much, not enough –

Content, that’s what you’d call it.

Maybe the first step out of the age of content is to recognize this overfilling emptiness, the void under the illusion of limitlessness. The cultural marketplace of the Information Age is antithetical to art, and to culture, and to what we really need from them. We must content ourselves.