by Richard Farr

You might think London’s National Portrait Gallery is a temple of celebrity, and it’s true that many of the faces on these walls belong to mere royalty, or influential past Nabobs, or those more recently glossy with fame. But the people who draw me back again and again are the ones who get to be here only because they were freakishly good at something.

Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.

Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.

Thomas Gainsborough is all over the place to good effect next door, in the National Gallery, but his self-portrait here makes him look embalmed. It seems almost cruel to have placed him next to his contemporary Joshua Reynolds, whose own self-portrait demonstrates how far wit and brio can take you. A less successful Reynolds captures Samuel Johnson looking morose, or constipated; no greater contrast than with that prince among wits Laurence Sterne (Reynolds yet again), seen in full gloat after the publication of Tristram Shandy.

John Collier’s famous Darwin looms benignly down at us. There are acres of other Eminent Victorians too, half of them by George Frederick Watts: John Stuart Mill, William Morris, Matthew Arnold, Tennyson – people with so much talent and so much energy that they look as if their skins will burst. It makes me feel good about Watts that his portrait of Cecil Rhodes, one of those national heroes whose career details are not for the squeamish, is inferior, as if the artist could not bear to look at the man closely. But I’m seduced entirely by Frederick Leighton’s account of a feral Sir Richard Burton: half insane; a genocidal racist after Rhodes’ own heart; yet so incandescent with ability and ambition that something about his ugliness is beautiful.

John Collier’s famous Darwin looms benignly down at us. There are acres of other Eminent Victorians too, half of them by George Frederick Watts: John Stuart Mill, William Morris, Matthew Arnold, Tennyson – people with so much talent and so much energy that they look as if their skins will burst. It makes me feel good about Watts that his portrait of Cecil Rhodes, one of those national heroes whose career details are not for the squeamish, is inferior, as if the artist could not bear to look at the man closely. But I’m seduced entirely by Frederick Leighton’s account of a feral Sir Richard Burton: half insane; a genocidal racist after Rhodes’ own heart; yet so incandescent with ability and ambition that something about his ugliness is beautiful.

One of Watts’ subjects, Julia Margaret Cameron, became an important artist in her own right when late in life she was gifted a camera. Her haunting, gauzy chiaroscuros could have been made yesterday. We get to know, or feel we know, the astronomer John Herschel in volcanic old age. And Thomas Carlyle, another character as unsavory and as massively gifted as Burton, comes to us in a blurred image that suggests even Cameron’s lens could not contain him.

Down in the modern galleries Iris Murdoch waits for us, an astringent pleasure always though in this painting her intelligence has gone missing; she looks flattened, blunt, bovine, like a bad copy of the copy of Holbein’s Cromwell. Near her is an even more Olmec-monumental but in this case exquisitely sensitive head of Mo Mowlam, a famous person who ought to be more famous: Tony Blair said she was the sharpest political mind he’d ever encountered.

Down in the modern galleries Iris Murdoch waits for us, an astringent pleasure always though in this painting her intelligence has gone missing; she looks flattened, blunt, bovine, like a bad copy of the copy of Holbein’s Cromwell. Near her is an even more Olmec-monumental but in this case exquisitely sensitive head of Mo Mowlam, a famous person who ought to be more famous: Tony Blair said she was the sharpest political mind he’d ever encountered.

Chance or curatorial wit has placed two of my most beloved images only inches apart but in different rooms: they are hung back to back. You might think John Taylor’s ‘Chandos’ portrait of Shakespeare is too famous to bother looking at closely, but look you must. Flirt, you must! You can move in close enough to hear him breathe, and he’s every bit as maddeningly inscrutable and androgynously gorgeous as the Mona Lisa. Such multi-dimensional ambiguity. Such understated challenge. Such sexy eyes.

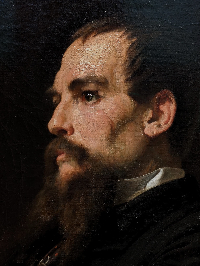

Still, I spend longer in conversation with his chief cheer-leader, on the other side of the same wall. Ben Jonson worked as a bricklayer. At least he tried to — he was constantly drunk. He gave it up for military service, and enjoyed killing a man in Flanders. Back in England he had his first play produced and started to make a hobby out of sleeping with other men’s wives, apparently because he found their husbands’ humiliation amusing. He was imprisoned for sedition on the strength of his second play, got out, was still constantly drunk, and killed his fellow actor Gabriel Spencer in a brawl that he attempted to dignify after the fact as a duel.

But this drunken adulterous brawling foot-soldier yobbo also made himself one of the most learned men of his age, and as a writer he might have been thought even greater but for the Shakespearean shade he stood in. The portrait, by the Flemish artist Abraham van Blyenberch, shows the scholar-poet and the lowlife combined in the one soul, the one face. No surprise that Jonson was interested in alchemists. The surface of the paint ripples with sly life, the face beneath it as angelic and monstrous as a pike looming up from the underside of a lake. You sense that he was observing you a split second ago. But his glance has slid away, his concentration interrupted; he is haunted by some recurring thought. Of death, perhaps? Perhaps being haunted by the thought of death was a condition of being that much alive?

But this drunken adulterous brawling foot-soldier yobbo also made himself one of the most learned men of his age, and as a writer he might have been thought even greater but for the Shakespearean shade he stood in. The portrait, by the Flemish artist Abraham van Blyenberch, shows the scholar-poet and the lowlife combined in the one soul, the one face. No surprise that Jonson was interested in alchemists. The surface of the paint ripples with sly life, the face beneath it as angelic and monstrous as a pike looming up from the underside of a lake. You sense that he was observing you a split second ago. But his glance has slid away, his concentration interrupted; he is haunted by some recurring thought. Of death, perhaps? Perhaps being haunted by the thought of death was a condition of being that much alive?

*

The NPG closed for an expensive overhaul in 2020 and only reopened last year; this visit was my first in a long time. The new entrance is better, but after so many millions far from thrilling. (Everyone’s eyes seemed to avoid, or merely miss, the lugubrious bronze doors by Tracey Emin. Perhaps only the February downpour was to blame.) Elsewhere there are changes both modestly good and modestly disappointing. Better light, only on the whole; better flow, ditto; a lingering impression of crowdedness not helped by my first stop being a cramped loo with both a design and a cleaning rota suitable to a provincial bus station.

Perhaps on the question of space I was biased not by the rain but by having also visited the impeccably fine V&A. The “new” NPG is still tacked onto the back of the National Gallery as something of an afterthought, and is still too cramped to show its collection well. Perhaps for that reason it has not solved the problem that illumination mixes poorly with glass and varnish that have been displayed too high. A portrait of William Harvey is typical: conversation with him requires hunting and craning for the right angle. New Visions and Voices: Contemporary Portraits by Women is consigned to one wall of a “room” that’s really a short narrow corridor, with many of the images eight feet up. Nothing on that row can be seen clearly.

Also poorly displayed — a mere afterthought in an intersection between four other spaces — are a handful of the portraits that Sir Godfrey Kneller and his assistants churned out in order to record all forty-plus members of the Kit-cat Club. Admittedly they aren’t stellar material anyway, with their mannered, production-line quality. Still, their subjects are interesting and historically important enough to deserve space. Addison, Steele, Vanbrugh, Walpole, Congreve: we want to stand back and see them as a group. We want to try at least to imagine that we can hear them talking. Of all the walls in history, one to be a fly on.

Also poorly displayed — a mere afterthought in an intersection between four other spaces — are a handful of the portraits that Sir Godfrey Kneller and his assistants churned out in order to record all forty-plus members of the Kit-cat Club. Admittedly they aren’t stellar material anyway, with their mannered, production-line quality. Still, their subjects are interesting and historically important enough to deserve space. Addison, Steele, Vanbrugh, Walpole, Congreve: we want to stand back and see them as a group. We want to try at least to imagine that we can hear them talking. Of all the walls in history, one to be a fly on.

While I’m on the subject of great talkers: possibly my favorite object in the whole collection is a painted plaster bust, by Benjamin Rackstrow, of the actor and impresario Colley Cibber. I have a lot of time for Cibber. When Alexander Pope decided to treat him with persistent and gleeful cruelty, the writing was good and the mud stuck. But Cibber’s autobiography, which Pope and others claimed to detest for its vanity, reveals a charming rogue, more likable and more self-aware than Pope could ever dream of being. Cibber is someone you want to meet, and the bust is so full of life and so eerily believable that here he almost is.

While I’m on the subject of great talkers: possibly my favorite object in the whole collection is a painted plaster bust, by Benjamin Rackstrow, of the actor and impresario Colley Cibber. I have a lot of time for Cibber. When Alexander Pope decided to treat him with persistent and gleeful cruelty, the writing was good and the mud stuck. But Cibber’s autobiography, which Pope and others claimed to detest for its vanity, reveals a charming rogue, more likable and more self-aware than Pope could ever dream of being. Cibber is someone you want to meet, and the bust is so full of life and so eerily believable that here he almost is.

What is all this talent? At the NPG you do run into examples of the natural knack, the unlearnable grace. I mean, it’s hard to believe that Anthony van Dyck or Nöel Coward ever had to try to do anything. But the dominant theme is something else, I think: an attitude. Men and women of mediocre accomplishments like to say that what’s worth doing is worth doing well. The best people on these walls despise well. Their sodality’s entrance fee is obsession. Monomania. Self-submersion. An infinitely charming variety of dogged, blind, bugger-you-all determination.

For charm, there are also many high-quality oddities here. A Yoruba wood-carving of Queen Victoria suggests what would happen if you crossed a minatory god with a squirrel. A twin miniature by Gerlach Flicke, painted around 1550 in prison, features the artist himself and his friend, the pirate Henry Strangeways. With his lute and his fuddled look, Strangeways might be the backup strings in a folk-rock band from the English 1970s.

For charm, there are also many high-quality oddities here. A Yoruba wood-carving of Queen Victoria suggests what would happen if you crossed a minatory god with a squirrel. A twin miniature by Gerlach Flicke, painted around 1550 in prison, features the artist himself and his friend, the pirate Henry Strangeways. With his lute and his fuddled look, Strangeways might be the backup strings in a folk-rock band from the English 1970s.

In every case you are left with the feeling that you half-know — but still ache to really know — what you can never know: who was the human being who lived behind that expression?