by Mary Hrovat

There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

For example, I was lucky enough to have clear skies in March 1996 on the night comet Hyakutake made its closest approach to Earth; from a relatively dark site, it was visible near the North Star, its long faint tail sweeping the sky like a hand on a clock. I also got to see the conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in December 2020, the closest such conjunction since 1623. There were also a number of clear evenings before the conjunction, so I could watch the two planets drawing closer to each other on the sky. A viewing party for comet Hale-Bopp, on a night in 1997 when the moon was full and Venus was visible in the western sky after sunset, was notable for clouds coming and going, but we got to see the comet and the planet, and the moon was remarkably pink through hazy clouds.

However, we do get a lot of overcast nights. Indianapolis, the closest city for which I can find data, receives 55% of available sunshine; annually, it sees 88 clear days, 99 partly cloudy days, and 179 cloudy days. As a result, I’ve missed a fair number of lunar eclipses, meteor showers, and other astronomical events over the decades. When I was an astronomy student in the 1980s, I remember standing on the balcony of the observatory with a classmate, wondering whether the clouds that had moved in were there to stay. The climate here fosters doubt about the possibility of clear skies.

∞

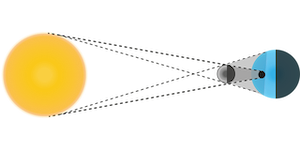

That said, I’ve been fortunate enough to see three solar eclipses in Indiana. On May 30, 1984, I saw a partial eclipse in which the moon covered maybe 50% of the sun. Several hundred miles to the south, the eclipse was annular (where the moon appears slightly smaller than the sun and thus doesn’t cover it completely, leaving a circle of sunlight visible around the moon). I briefly considered trying to go see this more exciting spectacle, but that idea was impractical for various reasons. So I stayed in Bloomington and watched the eclipse by viewing a large image of the sun projected onto a wall at Indiana University’s Kirkwood Observatory. I was thrilled. It was my first visit to the observatory; two years later, I’d have my own key for a class in observational techniques. Those were heady days. At the time of the 1984 eclipse, I was sure that someday I’d travel to see a total eclipse. I was so taken with the idea of seeing Earth from space that I even thought for a while, in my student days, that I’d like to be an astronaut.

In 1994, finished with school and working a clerical job in Bloomington, I went with several friends to a site in northern Indiana that was on the centerline of an annular eclipse. It was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen in the sky. The light was peculiar, and the darkening of the sky clearly attracted the attention of birds. The thin bright circle of sunlight around the moon was delicate, perfect, ephemeral. The park we visited wasn’t crowded, even thought it was right on the centerline of the eclipse; I don’t remember seeing many other people there. Afterward we hiked and looked at spring wildflowers and skipped stones. It was a wonderful experience. At the time, I still thought I’d someday travel to see a total eclipse.

On August 21, 2017, a deep partial eclipse was visible in Bloomington. The eclipse was total in far southern Illinois, and I thought about driving over to see it there. But the logistics of a large number of people converging on a small area for a brief event were discouraging, and anyway it wasn’t a sure thing that the sky would be clear. Instead, I stayed in town and watched the eclipse with my older son and one of my grandsons. There were some clouds early on, but it cleared enough to see the sun when the eclipse was at its maximum (approximately 94% of the sun was covered). The light became eerie; tiny crescent suns appeared on sidewalks as sunlight passed through the pinhole openings between leaves. It was the first day of classes at IU, and on my walk home, campus appeared lively but not overly crowded.

∞

Bloomington itself is on the path of totality for a solar eclipse on April 8. I’m very excited about that, because I’ve never seen a total eclipse. In addition, the sun is near the peak of its sunspot cycle, which suggests that the corona, the glowing halo visible when the sun is hidden by the moon, will be particularly interesting. The duration of totality will be a respectable four minutes here. However, as a long-time Indiana stargazer, I’m trying to temper my enthusiasm and brace for clouds.

In April, Indianapolis sees, on average, 6 clear days, 7 partly cloudy days, and 17 cloudy days. ClearDark Sky reports that historically, skies have been clear 38% of the time in past Aprils around the time the eclipse will occur. The odds aren’t great. A partial solar eclipse in November was clouded out, and I jokingly said that this meant we were owed cloudless skies for the total eclipse. Yeah, right.

After the 2017 eclipse, I wondered if I should plan to view this year’s eclipse from a location with better weather. Skies are more likely to be clear to the south and west of Bloomington, in particular where the path of totality runs through part of west Texas. Again, though, the idea of traveling didn’t appeal, even if I could have afforded it. As much as I enjoy seeing new places, it takes a lot out of me, and going to a place to which large numbers of people are flocking seems like the worst sort of travel. When I was in Paris in June 2011, one of the few things I regretted was visiting the inside of the palace at Versailles: it was too crowded, with too many people standing in front of things I wanted to see so they could take selfies. That taught me something about going where everyone wants to go.

It turns out that locally, Bloomington will be one of the places where everyone wants to go. County officials say we can expect 300,000+ visitors; we’re being warned to buy groceries well in advance and to expect heavy traffic, slow food delivery, and possible effects on cellular service. I’d been thinking of walking over to see the eclipse with my son and his family or with a friend. However, it’s becoming clear that any travel, even on foot, might be unpleasant. I can’t really imagine an additional 300,000 people here, but if they’re arriving by car, I can easily envision congested streets and impatient drivers trying to get someplace in time to watch the eclipse unfold.

My best option seems to be staying in my own yard, which is actually an appealing prospect. I spend quite a bit of time looking at and photographing the sky from my neighborhood and my yard anyway. Weather permitting, it would be fantastic to see a total solar eclipse taking its place in the unending cycle of sunrise, sunset, clouds coming and going, light shifting slowly over the course of the day and the year. This eclipse, as unusual as it is, is on some level just another thing the world shows me (or doesn’t show me, as the case may be).

∞

For financial and other reasons, I doubt now that I’ll ever travel to see a total eclipse, and I gave up my dreams of space travel long ago. It might seem that I’ve been telling a story of a life becoming narrower. However, it feels like I’m coming into my own, as if my life is becoming slower and deeper and richer. I wouldn’t have thrived under the pressure of astronaut training, or even under the competition for post-doc positions in astronomy, much less the many moves and the amount of travel that would have been required. I love to get to know new places, but travel is disruptive for me. My favorite type of trip would be to spend a long time exploring a small region; at heart, I want to dwell.

As I try to balance contentment and effort, stability and novelty, appreciating what’s in front of me and seeking something better, I’m realizing how much I’ve always leaned toward contentment, stability, and appreciation. Most humans throughout history haven’t seen a total solar eclipse. Most humans never see even a small fraction of the wondrous events and places of their lifetimes. Conversely, nature rewards close attention even in its most ordinary and everyday manifestations. I’ve learned that I’m happiest and most comfortable giving my attention to the low-key and the quotidian. I hope to see the eclipse, but the slow intricate beautiful world of nature will be there waiting for me even if I don’t.

∞

The American Astronomical Society provides information about how to view a solar eclipse safely.

∞

Image by fractional from Pixabay

∞

You can read more of my work at MaryHrovat.com or in my free newsletter,

Slow Quiet.