by Malcolm Murray

If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February was all about investments rather than safety, OpenAI now releases model with allegedly only days for testing and we almost had a 10-year moratorium on any US state AI legislation.

If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February was all about investments rather than safety, OpenAI now releases model with allegedly only days for testing and we almost had a 10-year moratorium on any US state AI legislation.

This is why it was a relief and a happy surprise to see that the final CoP, and I am here focused on the Safety and Security chapter, which is my domain, ended up being a really, really good document. There are three main reasons why I am excited about the final CoP: the baseline it sets, its risk management nature and the democratic process by which it was created.

An Unavoidable (Positive) Elephant in the Room

It is too early to tell whether we will see the same kind of “Brussels effect” for the AI Act that we saw for other EU legislation, such as GDPR. However, by producing a very strong CoP, the EU has set a very strong foundation. The existence of the CoP now provides an unavoidable baseline to which all future AI regulation and policy will be compared. It introduces an elephant in the room (in a good way), one that companies and countries can’t avoid referencing whenever AI policy is discussed.

The CoP is technically voluntary, but it seems likely that companies will want to sign it, since it is the most straightforward way to comply with the Act and removes much legal uncertainty. The EU has also signaled that they will provide a grace period for signatories before enforcement starts in August 2026, providing another key benefit.

The news that both Mistral and OpenAI plan to sign is a strong signal in this direction. Read more »

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

In reading about attachment theory,

In reading about attachment theory,

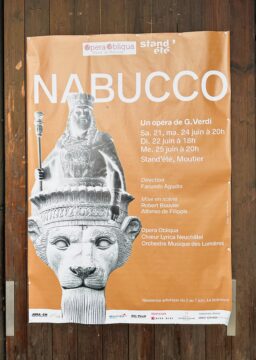

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

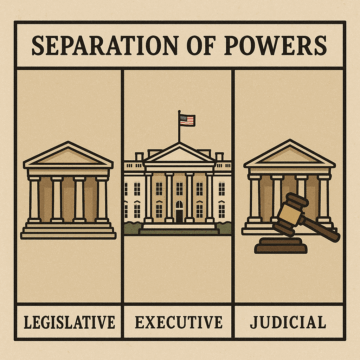

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.

Gozo Yoshimasu. Fire Embroidery, 2017.

Gozo Yoshimasu. Fire Embroidery, 2017.