by David Kordahl

Thomas Kuhn’s epiphany

In the years after The Structure of Scientific Revolutions became a bestseller, the philosopher Thomas S. Kuhn (1922-1996) was often asked how he had arrived at his views. After all, his book’s model of science had become influential enough to spawn persistent memes. With over a million copies of Structure eventually in print, marketers and business persons could talk about “paradigm shifts” without any trace of irony. And given the contradictory descriptions that attached to Kuhn—was he a scientific philosopher? a postmodern relativist? another secret third thing?—the question of how he had come to his views was a matter of public interest.

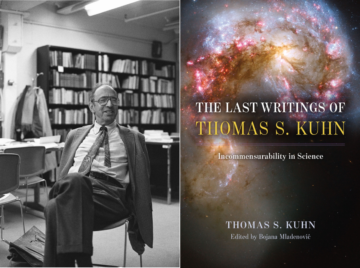

Kuhn told the story of his epiphany many times, but the most recent version in print is collected in The Last Writings of Thomas S. Kuhn: Incommensurability in Science, which was released in November 2022 by the University of Chicago Press. The book gathers an uncollected essay, a lecture series from the 1980s, and the existing text of his long awaited but never completed followup to Structure, all presented with a scholarly introduction by Bojana Mladenović.

But back to that epiphany. As Kuhn was finishing up his Ph.D. in physics at Harvard in the late 1940s, he worked with James Conant, then the president of Harvard, on a general education course that taught science to undergraduates via case histories, a course that examined episodes that had altered the course of science. While preparing a case study on mechanics, Kuhn read Aristotle’s writing on physical science for the first time.

At first, he was surprised at how Aristotle “appeared not only ignorant of mechanics, but a dreadfully bad physical scientist as well.” But as he continued to read, Kuhn did something unusual for a scientist. He wondered whether Aristotle might not be simply ignorant of physics, but whether he, Thomas Kuhn, had not properly understood—that is, whether Aristotle could have meant something other than his own first first guess:

I was sitting at my desk with the text of Aristotle’s Physics open in front of me and with a four-colored pencil in my hand. Looking up, I gazed abstractedly out of the window of my room—the visual image is one I can still recall. Suddenly the fragments in my head sorted themselves out in a new way, and fell into place together. My jaw dropped, for all at once Aristotle seemed a very good physicist indeed, but of a sort I’d never dreamed possible. Now I could see why he had said what he’d said, and why he had been believed. Statements that I had previously taken for egregious mistakes now seemed to me, at worst, near misses within a powerful and generally successful tradition.

This passage is from “Regaining the Past,” the first of three lectures in The Presence of Past Science, a lecture series Kuhn delivered in 1987. Kuhn discussed there how Aristotle, Volta, and Planck presented difficulties for contemporary historians, due to the incommensurability of their language with ours. Aristotle’s conception of motion, Kuhn argued, cannot be directly translated into Newtonian terms. The historian must become bilingual, speaking with both Aristotle and Newton on their own language.

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

Critics might cite the Damascus-road quality of Kuhn’s Aristotelian conversion testimony as evidence of his irrationality. Yet for supporters, this was a powerful example of his historical insight. Kuhn had hit upon a real issue in scientific history. As he would write in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a mature scientific community is, “like the typical character of Orwell’s 1984, the victim of a history rewritten by the powers that be.”

In Structure, Kuhn distinguished between periods of normal science and periods of crisis, during which revolutionary reforms occur. Every scientific era hosts its share of empirical anomalies, those observations that have not yet been folded into the accepted theoretical framework, the framework that Kuhn famously (if inexactly) dubbed a “paradigm.”

Normal science treats anomalies as puzzles to be solved using standard tools. But during periods of crisis, the buildup of anomalies may lead to a revolution. As a physicist, Kuhn frequently reached for the Copernican revolution—the subject of his first book-length history—and the quantum revolution—the subject of his last—as his two most familiar examples. After such revolutions, scientists working in their new paradigms reweave the web of history, forgetting old practices and erasing old objections so completely that, in retrospect, all changes appear to have been inevitable.

Latter-day critics of Kuhn have charged that his description of scientific progress is self-undermining. If science is just pinging from one paradigm to another, never converging on the reality of things, why does science seem, nevertheless, to progress? If pre- and post-revolutionary paradigms are really so “incommensurable” as Kuhn suggested, how is scientific history even possible? How is it that scientists are stuck in a particular paradigm, while historians can glide between them? Furthermore, in a world of incommensurability, how is communication possible at all?

The Last Writings of Thomas S. Kuhn

The Last Writings is the second posthumous Kuhn collection. The first, The Road Since Structure: Philosophical Essays, 1970-1993, overlaps considerably with The Last Writings, but was considerably more fun to read.

The centerpiece of The Road Since Structure was an address of the same title. In that lecture, Kuhn teased his audience with the promise of new book that would be as groundbreaking as Structure. “As a number of you know, I’m at work on a book, and what I mean to attempt here is an exceedingly brief and dogmatic sketch of its main themes.” Kuhn characterized his late views as “a sort of post-Darwinian Kantianism,” views that were “post-Darwinian” in their acceptance of language as an evolved tool, but “Kantian” in the sense that they took on board the lesson that humans can only experience the world through that evolved language.

Kuhn’s unfinished book, The Plurality of Worlds: An Evolutionary Theory of Scientific Development, comprises roughly the last 60% of The Last Writings by page count. Those who have already read The Road to Structure may want to read Plurality, but I can’t recommend it to first-time Kuhn readers, given the question mark always hangs over unfinished works.

But while questions of finality fog any reading of The Plurality of Worlds, they do not apply to the opening 40% of The Last Writings. Both the opening talk, “Scientific Knowledge as Historical Product,” and the aforementioned lecture series, The Presence of Past Science, were delivered during Kuhn’s lifetime. Since we can accept these opening talks without too much suspicion, I will review them now as uncontroversial additions to the Kuhnian corpus.

“Scientific Knowledge as Historical Product”

“Scientific Knowledge as Historical Product” is a typically Kuhnian defense of the historian of science as a pivotal figure in philosophy. In it, Kuhn uses Francis Bacon and René Descartes as exemplars of two opposing—and now overturned—orientations toward scientific knowledge. And what overturned them? Why, historians like himself.

In Kuhn’s telling of this story, Bacon supposed that scientific knowledge could be made solid by resting every claim on sense-data, while Descartes supposed the key was to discover correct propositions from which all other conclusions could be derived. But in the twentieth century, the philosophical development of the Duhem-Quine thesis allowed historians to notice that observations are inevitably muddied by theoretical assumptions, such that it proved fruitless to claim that words and the world, or scientific theory and practice, could be cleanly separated.

“For the historian, in short, unlike the traditional philosopher of science, the advance of science is marked less by the conquest of ignorance than by the transition from one body of knowledge claims to a different, though overlapping, set.” This leads to a revised vision of science, where the scientific community is more important than the individual genius, and where the scientific historian’s goal is no longer to show how scientific inquiry brought us away from ignorance and toward truth, but is instead to recapture the “integrity of an out-of-date scientific tradition.”

And where would this lead? Kuhn suggested it would transform “our understanding of knowledge as well. That transformation is, I believe, also underway.”

There the lecture ends. It’s an effective piece, but is more of a promise than a payoff. I was left, from this, with a sense that Khun’s critics a have a point, that his vision of science was purely descriptive and reactive, with little guidance for future scientists.

The Presence of Past Science

Yet in The Presence of Past Science, sympathetic readers can see Kuhn grappling with the differences between his own needs, as a philosopher and historian, and the needs of current scientists. But even there, the reversal only comes in the third lecture.

“Regaining the Past,” the first lecture in Presence, describes concerns about paradigms and incommensurability. Kuhn had tired of the word “incommensurability” by the time he gave these talks, and in the second lecture, “Portraying the Past,” he remarked, “untranslatable is a better word than incommensurable for what…I had in mind, and I shall be using it here.” Kuhn remarks that “translating science” and “translating literature” are similarly difficult tasks, since, just as there may be no equivalent word to convey an abstract concept across two languages, describing the ideas of past science in terms of present science may lead to mistranslations.

Kuhn expresses himself eloquently on this issue:

My point, let me say again, is not that one and the same sentence was true for the Greeks and is false for us. Rather I am saying that, though the two word strings are the same, the statements made with them are different, and there is no truth-preserving way which the Greek statements can be rendered in our later lexicon. In particular, it will not do to substitute for the Greek equivalent of planet some string of terms providing a putative definition in terms of features used by the Greeks. There is no such string….

The third of these lectures, “Embodying the Past,” addresses the notion originally broached in the tenth chapter of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions—the notion that separate communities live in different worlds.

This is perhaps the most puzzling aspect of Kuhn’s philosophy. Kuhn mentions that critics have asked him, “Do you mean that there were witches in the seventeenth century?” And he admits, “I have sometimes answered, yes, but always in a most equivocal and embarrassed tone.”

Kuhn recognizes the strange tension that exists within this stance. He knows it is important to allow for the possibility of scientific progress (as a modern man, Kuhn would not himself say that there are witches), while at the same time he is unwilling to give up the philosophical principle that worlds are made up of both mental and physical characteristics (this is Kuhn’s “vaguely Kantian” position that perceptual categories shape experience—including, yes, that of whether or not another person is a witch). So how, then, can any change be made?

Kuhn’s initial answer was in his earliest work. Revolutionary change occurs when enough empirical anomalies pile up to motivate a change of lexicon—and a corresponding change of worlds. Yet Kuhn also acknowledges, in these last writings, that the “Whig history” he had spent a career denouncing also plays a fruitful role in conceptual change. Philosophers and historians may find it useful to look at the science of the past by acquiring the discarded viewpoints of those who practiced it, but Kuhn concedes that this will not do for scientists, for whom it will be more useful to describe the past directly in terms of our present lexicon.

After all, in the view of modern scientists, “the Sun was always a star, motion was always a state governed by Newton’s first law, the power of the battery was always chemical, simultaneity was always relative, and so on.” This is not to say that Whig history is to be preferred as a mode of philosophical or historical inquiry, but that progress toward the future may require a different set of tools than excavations of the past.

Kuhn’s ultimate acceptance of “the cleavage between those who need history to look back and those who need it to look ahead” is one of the major revelations of The Last Writings. It points toward an appreciation of how seemingly contradictory stories can be useful in contrasting contexts, and how, before denouncing such stories, one must be alert to their varied uses. (As a side note, I should mention that I explored a similar ideas in my last 3QD column, “A Paradox Concerning Scientists and History,” and was not entirely pleased at being scooped by some three decades.)

The Plurality of Worlds

In the introduction to The Last Writings, Bojana Mladenović poses a pointed question. “Can an unfinished work be a successful one?” She answers her own question immediately: “The straightforward answer seems obvious, and negative: Kuhn did not live to complete Plurality, and what is published here is not what he wanted to see in print.” Mladenović softens this “straightforward answer” by the end of her essay (“Kuhn’s dynamic method of perennially searching, restructuring, focusing, and expanding would have never ended in a definite conclusion or the final resting of his case; but that, I think, is what success in philosophy might look like”), yet a question remains. How seriously should we take Plurality as a source of Kuhn’s final opinions?

There at once is too much here to be dismissed, and too little to be convinced. The manuscript of Plurality presented in The Last Writings begins with a dense, thirteen-page abstract, in which the contents of nine planned chapters are sketched out. Six of these chapters are drafted in the pages that follow, but these drafts are not all equal. Editorial endnotes (“Kuhn’s note in the margin: ‘This seems to me now clearly wrong…’”) further undermine the reader’s confidence.

This uncertainty is enhanced by the strangeness of the text itself. The first three chapters seem to be entirely characteristic of Thomas Kuhn, revisiting his “hermenutic” methods of historical analysis—essentially, the same immersive methods he stumbled upon as a young man reading Aristotle. But by the third chapter, we are already in quite uncharted territory.

In the drafted chapters, Kuhn puzzles over questions of how humans and other animals are able to distinguish between various objects. This leads to a sharpened up version of Kuhn’s “vaguely Kantian” project, with an attempt to grapple with the fundamental categories of human thought.

In this context, “incommensurabilty” takes on a specific and technical meaning. It would be foolish for me to attempt a summary Kuhn’s scheme, but Kuhn seems to have tried to construct a semi-empirical account of what sorts of scientific descriptions are possible, given the constraints of human biology and psychology. The drafts wind from executive summaries of infant perception experiments to categorizations of “natural kinds” that adults have historically identified, always attempting to fit various perceptions into a more general model.

What stopped Kuhn from finishing his book? As before, there is a straightforward answer (Wikipedia informs me that Kuhn was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1994, and died in 1996), and a broader question.

Thomas Kuhn’s incommensurable legacy

People who have spent time thinking about Thomas Kuhn tend to have strong feelings about him. Kuhn has his haters. To take just one prominent example, in the early 1990s the sociologist Steve Fuller compared Kuhn to the character Chauncey Gardener in Being There, a simpleton whose idiocy is misinterpreted as profundity. Fuller would later write a book, Kuhn vs. Popper: The Struggle for the Soul of Science, whose last chapter was titled, “Is Thomas Kuhn the American Heidegger?”—where the comparison was to Heidegger’s Nazism, not his genius.

I am not a neutral party in the Kuhn Wars. My own most widely read review remains a pan I wrote a few years ago of Errol Morris’s book, The Ashtray (Or the Man Who Denied Reality), in which Morris not only claimed that Kuhn threw an ashtray at him during office hours, but also attempted to tie Thomas Kuhn to Donald Trump.

Which side of the dividing line between haters and lovers of Thomas Kuhn one finds oneself depends on whether one thinks of Thomas Kuhn as basically a friend or basically an enemy of the truth. Haters often characterize Kuhn as an enemy, while admirers like me suppose that he was a friend, broadly construed.

Kuhn thought correspondence theories of truth were dead in the water, but he was reluctant to lump himself in with his “relativist” admirers. But this did not stop those admirers from claiming him. In “Thomas Kuhn, Rocks and the Laws of Physics,” one of those “relativists,” the philosopher Richard Rorty, wrote, “I always hoped that when [Kuhn] published the book on which he was working in the last decade of his life—a return to the controversies raised by Structure—I would be able to cite chapter and verse to show him we had been preaching pretty much the same doctrine.”

In her introduction to The Last Writings, Bojana Mladenović speculates that Kuhn’s inability to come up with his own satisfactory theory of truth was one of the major hurdles that kept him from completing The Plurality of Worlds. This may be. But now that we have at least a part of the Plurality, the internal tensions in the work of Thomas Kuhn can be considered anew.

On the one hand, one of the main lessons of Kuhn’s work is that communication can easily break down between rival communities. But this comes with the contrasting lesson that such breakdowns can be breached—but only if we become “bilingual,” taking on the language of the group whose vision of the world we wish to understand.

The abstract for The Plurality of Worlds contains the striking suggestion that Kuhn had considered just how broadly this idea might be applied, and that he intended for the last chapter of his book to address this. Though I believe this summary is by Mladenović, and not Kuhn, the framing is suggestive:

There is a sense in which we always move from one world to another incommensurable world. We do pass between worlds as we pass from home to office or to classroom. There are no smooth transitions between them, and we do damage by failing to notice the thresholds that we cross. (For example: treating one’s children as one’s students, or vice versa; or treating a family argument as as a judicial proceeding.) On such occasions, we, as it were, commit category mistakes. When we transition between the worlds smoothly, when we are correctly handling incommensurable lexicons and situations, we are, in our actual lives, bilingual….

When we “transition between worlds” today, many of us habitually presume that, in disagreements, our opponents are simply lying. Of course, this happens sometimes. But more common, I think, are interactions involving the Kuhnian difficulties of translation. One of the enduring lessons from Thomas Kuhn is that of just how difficult it is to imagine the mental lives of others, and of just how easily truths can be lost in their transit from one mind to another.