by Eric Feigenbaum

“Peaches are $8.99 a pound!” my friend texted me yesterday.

“This is the valuable package,” a very nice man named TJ who works at Trader Joe’s but disavows any personal connection said to me as he packed my grocery bag, “It has the eggs!” $5.49 a dozen for jumbo organic free-range eggs was the best deal around.

Despite the recent eight percent drop in oil prices, a gallon of gas in my area still costs almost $5.00 per gallon.

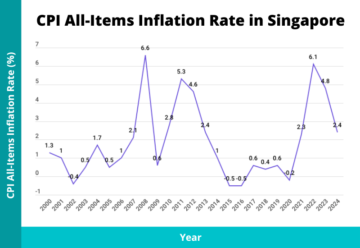

Inflation is not only real, but has been one of the defining issues of our decade. The Consumer Price Index for my region of the country (Western United States) was increasing by as much as 8.3 percent in May of 2022 and still hovers at monthly increases on roughly 2.8 percent. Food costs are still increasing at 5.1 percent per month and most forms of housing in excess of 3.1 percent. Americans have not just faced inflation, but have been hit hardest where it hurts – on necessities and everyday staples.

To their credit, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve have given inflation their full attention and have been working hard to curb it with their main and most accessible tool being interest rates. Raising the cost of capital and borrowing slows the flow of dollars in the economy causing people to spend less. In turn, the cost of goods can slow if not drop because of decreased demand. Raising interest rates is a way to hit the brakes on an overheated economy.

Singapore deals with inflation differently. In fact, it does so in a way completely unique in the world – by focusing first and foremost on consumer prices. Quite simply, the Monetary Authority of Singapore – their version of a central bank – uses consumer affordability as its Northstar.

But how? That’s kind of a crazy thing for a central bank to do. The Fed certainly doesn’t have the kind of power. How does the MAS (which cleverly means Gold in Malay)?

Singapore tries to break what in international economics is often called The Impossible Trinity or The Trillemma.

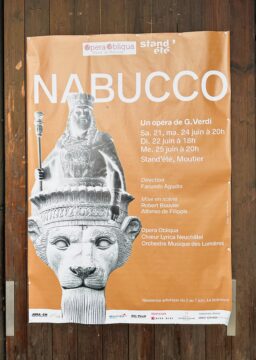

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.

Gozo Yoshimasu. Fire Embroidery, 2017.

Gozo Yoshimasu. Fire Embroidery, 2017.

In a culture oscillating between dietary asceticism and culinary spectacle—fasts followed by feasts, detox regimens bracketed by indulgent food porn—it is easy to miss the sensuous meaningfulness of ordinary, everyday eating. We are entranced by extremes in part because they distract us from the steady, ordinary pleasures that thread through our daily lives. This cultural fixation on either controlling or glamorizing food obscures its deeper role: food is not just fuel or fantasy, but a medium through which we experience the world, anchor our identities, and rehearse our values. The act of eating, so often reduced to a health metric or a social performance, is in fact saturated with philosophical significance. It binds pleasure to perception, flavor to feeling, and the mundane to the meaningful.

In a culture oscillating between dietary asceticism and culinary spectacle—fasts followed by feasts, detox regimens bracketed by indulgent food porn—it is easy to miss the sensuous meaningfulness of ordinary, everyday eating. We are entranced by extremes in part because they distract us from the steady, ordinary pleasures that thread through our daily lives. This cultural fixation on either controlling or glamorizing food obscures its deeper role: food is not just fuel or fantasy, but a medium through which we experience the world, anchor our identities, and rehearse our values. The act of eating, so often reduced to a health metric or a social performance, is in fact saturated with philosophical significance. It binds pleasure to perception, flavor to feeling, and the mundane to the meaningful. Since 1914, the Federal Trade Commission ‘s mission has been to enforce civil antitrust and unfair competition/consumer protection laws. The question is whether this mission has been supplanted—whether the FTC under Trump 2 .0 is becoming the Federal Political Truth Commission.

Since 1914, the Federal Trade Commission ‘s mission has been to enforce civil antitrust and unfair competition/consumer protection laws. The question is whether this mission has been supplanted—whether the FTC under Trump 2 .0 is becoming the Federal Political Truth Commission.