by Marie Snyder

“As the world falls around us, how must we brave its cruelties?” —Furiosa

Imprisoned climate activist, Roger Hallam, recently wrote about the necessity of expanding emotional well-being as we face bleak events happening around the world. While climate scientists try to “help people through the horrific information that they are being given,” they also need a way to manage their emotional reactions. We can no longer afford to merely distract ourselves from the inner turmoil. Beyond climate, we could very well be entering into a period of much greater conflict at a time of even more viruses, some destructive to our food system. When the watering hole gets smaller, the animals look at one another differently.

To move forward with compassion, at a time when divide and conquer strategies have created polarization and infighting, seems to require an effort from each one of us.

Hallam writes,

“We might want to think about why saint-like people are enormously influential, even powerful. . . . They see the world as dependent upon the mind. . . . They are not enslaved by the world; their minds are intent, driven even, to change it. They do not see this as an end in itself.”

He explains the journey toward collective action as beginning with exploring the self as it relates to reality. The part of interest to me is this:

“Some people are so into themselves that they find it almost impossible to get out of themselves. They are stuck, enmeshed. Children are often like this. They are literally overwhelmed by their emotions. . . . You see it a lot in prison–people so full of their distress, their anger, and rage, they cannot see themselves at all. . . . The ability to reflect on yourself, on your emotions and your behavior, leads on to a more general idea, and that is transcendence. This might be described as a deep ability to move outside of oneself, to look at oneself from the outside, simply to watch. . . . The more you practice doing it, the stronger you get at doing it. . . . The essence of being human is nothing to do with our being in this world–it is to do with having a choice.”

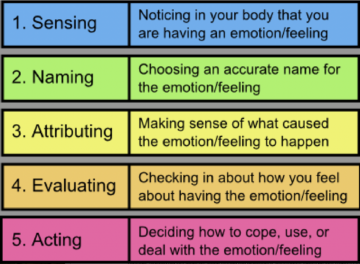

The ability to choose to be responsive instead of reactive can be developed and refined through intentional introspection. This isn’t anything new; it’s an old truth ignored until it becomes crucial to our survival.

When we feel unmoored, it helps to be able to find some center inside. Inner awareness is not a matter of seeking out a hidden traumatic moment, or making healing an element of identity and boring all our friends to death about it, but taking a bit of time here and there to notice what’s going on with us. It’s not a new age thing; we need to look inward and know thyself in order to avoid making a bigger mess of things. Philosophers have been telling us to do this for millennia, but most of us thought it was optional.

Plato, Aristotle, and Stoics were all about self-control, advising us to contemplate to improve the ability to act from reason instead of being tossed around by the passions. However, there’s a common theory being espoused today of processing emotions, which, as far as I understand it, is less about control over and more about being released from the power of emotional baggage. In that case, it’s more reminiscent to me of the story Descartes told of falling in love with a girl with a squint. In 1647, in Letter to Chanut, (6. vi.) he wrote about his feelings for a girl from his childhood colouring his further judgments for decades:

“When I saw persons with a squint I felt a special inclination to love them simply because they had that defect; and I didn’t know that that was why. But as soon as I reflected on it and saw that it was a defect, I was no longer affected by it. . . . so a wise man won’t altogether yield to such a passion.”

This experience resonated to me when I first read it. I was enamoured with a man who really didn’t make sense for me, yet I couldn’t shake that desire for him. Then one day it dawned on me that he reminded me of a childhood friend, not in his looks or attitude, but from just a few specific, familiar gestures he used when talking. As soon as the connection was made, the longing disappeared like magic! So it seems to follow that a less pleasant emotional response could also be subdued once we connect it to where it started.

What I really like about this illustration of processing theory, even if it’s not as the theory was originally intended, is that it applies beyond any parenting mishaps or abuses. We’ve mainly bought into the idea that we get stuck in life by emotional barriers because of some childhood trauma. Something seriously bad had to happen for us to have any problems as an adult. But there’s so much buried stuff in there affecting all we do, from a tiff with friends or disappointing a teacher or not making the team, on top of all the things we wished were different in our home lives. The very necessary socialization process alone is going to lead to buried emotional experiences that colour the rest of our lives. Mom’s sudden stern rebuke of, “Don’t hit the baby!” that one time, amid all the forgotten times she gently told us “ta ta,” could have been what provoked us to swallow our anger. We don’t need to have been traumatized to have had some needs go unmet; we just need to have had some barriers placed on our behaviours, which is necessary.

We can connect this knowledge that mom putting down her foot can lead to some repressed stuff to some newer questionable parenting choices. The fear of ever causing problems in our own kids sometimes leads well-meaning parents to avoid giving kids any kind of boundaries or ever saying “no” to them. We don’t want them to repress any feelings!! But this path just makes kids rudderless or worse! Kids need to be given limitations, and then it’s our task, as adults, to work through the pieces keeping us stuck. There’s just no getting around that. Growing up is messy and fraught.

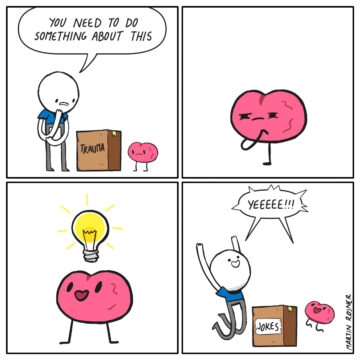

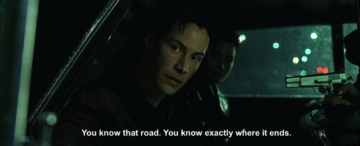

This is not about old traumas, a word that has experienced some serious definition creep. This is about old narratives that are subconsciously driving the bus down roads we’ve seen before and haven’t found fulfilling. Once we notice the connections, once we realize what makes us react so strongly to a stimulus, then those connections begin to dissolve, and we’re free to make a choice: to respond instead of just react.

“Emotion, which is suffering, ceases to be suffering as soon as we form a clear and precise picture of it.” ~ Viktor Frankl in Man’s Search for Meaning

Freud followed the footsteps of Plato with elevating self-control, but Jung had a more all-encompassing approach. Like Hallam, Jung viewed psychoanalytical exploration not just as a way to help individuals, but as pivotal to reducing evil in the world (from Psychology and Religion):

“Unfortunately there can be no doubt that man is, on the whole, less good than he imagines himself or wants to be. Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is. If an inferiority is conscious, one always has a chance to correct it. Furthermore, it is constantly in contact with other interests, so that it is continually subjected to modifications. But if it is repressed and isolated from consciousness, it never gets corrected, and is liable to burst forth suddenly in a moment of unawareness, thwarting our most well-meant intentions. . . . Mere suppression of the shadow is as little of a remedy as beheading would be for headache. . . . The shadow is merely somewhat inferior, primitive, unadapted, and awkward; not wholly bad.”

The less we open it up to have a look, the more it affects our decisions and behaviours. That inner stuff isn’t pure evil; it’s just anything we don’t want to look at. Because much of it was stored away as children, it’s primitive and a bit wild and chaotic. It’s not just the bad stuff, but also normal reactions that weren’t seen as appropriate by someone along the way, or creative impulses that weren’t appreciated. It can be unnerving to think we have parts of us so socially embarrassing, but we’re missing out on an ability to live with the entirety of ourselves if we keep them locked up. It can feel shameful to acknowledge the worst of ourselves, so it might help to remember that all the shiny perfect-looking people around us have to deal with this too.

It takes courage to get down to this crawl space in the mind.

The dark shadowy bits can sometimes be seen in dreams, but more clearly in our strongest affiliations and projections. When we’re part of a group that feels unquestionably best (sports, politics, religion…), it points to something in us. When we really react to someone in a way that others don’t, when we can’t believe they’re so stuck up or quiet or whatever, whenever it’s unreasonably annoying to us, then it’s likely part of us. We can ask people close to us what we’re really like, and notice any defensiveness. “What do you mean I’m needy?!” Finding elements from the shadow can feel like being stung or being hit with a ton of bricks, and we instinctively fight them off; luckily, noticing that can be the start to resolving it.

Years ago I saw a Jungian analyst who told me to imagine a little bird on my shoulder. Whenever I would be irritated or enraged by someone, the bird should speak up and ask me, “What part of YOU is this?” Just paying attention to it at first seems to be a good start.

Accepting that we’re wounded, we live life differently than if our only concern is to overcome the wound. — Thomas Moore in Care of the Soul

Whatever you’ve been led to believe is bad is likely stuck in the crawl space. Ignoring it just makes it stronger and sneakier. The work we do, or fail to do, shows up in our relationships with partners, neighbours, colleagues, communities, and our children. Whatever we don’t address spills over into other people’s lives. Opening this Pandora’s box isn’t about making us happy, though, but about making us whole and able to be more conscious of and accountable for our choices. If we can get curious about it, interview it, or step into it, imagine doing the very thing we hate, it can help resolve some of this content.

Some of us have been told to stop hitting or biting, and might have understood it as a rule to never be angry. Others have had opinions shut down so they learned to stop showing off. Others were told to get a grip when they pitched a fit at school, which stymied their sensitivity. From what I understand of this very complex theory, the problem isn’t in the practice of setting up some boundaries for behaviours in children, although that can be done thoughtfully or carelessly for sure, but in later exploring the types of limits we blindly accepted long ago so that we can consider how reasonable they are at this point in our lives. The shadow is a functional and necessary part of ourselves. If we didn’t inhibit behaviours, we’d all be in jail and society wouldn’t be able to function. But some of what’s been inhibited might give us some useful creativity or a much needed element of wildness or openness to our lives. There’s certainly more to life than just being pleasant.

Most importantly, though, the more we hate on others, the more that bounces right back at ourselves. The more we clean out the crawl space, the less we feel the need to judge and condemn harmless actions and attitudes. It would be really nice if everyone else could take the time to do some of this work, particularly some CEOs and governmental leaders who are driven by hatred or selfishness and affecting the actions of others. But all we can control at this juncture is ourselves. If we make an attempt, then, just maybe, we can trudge through the next few difficulties with some well deserved empathy for ourselves and others.

Jung conceptualized the idea of an inner child in us that can be helped by being acknowledged; the child archetype informs our actions. John Bradshaw took us further down that road in the 1980s, adding another way to process it all, and Richard Schwartz seemed to turn the shadow into the exiled self part in the 1990s with Internal Family Systems therapy, which is recently gaining more popularity.

“Whatever cannot obey itself, is commanded. … I am that which must ever surpass itself. … All suppressed truths become poisonous.” Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra: 34

There’s a science to it as well: In the 1970s, Peter Lang started exploring reducing the intensity of emotional responses, specifically fear, through “mindful experiencing” of prior events. In the 1990s, Jaak Panksepp looked at finding emotional responses in the brain. Then many people flew with it in slightly different directions. Teasdale (2000) worked with depression and reactivate patterns of thinking to develop new relationships with the thoughts and feelings; Solms (2001) wrote on neuro-psychoanalysis and getting stuck in old neural pathways, and Engelhard et al (2010) hit on exploring emotional events while doing simple mental subtraction (but not complex subtraction) to reduce the vividness and intensity of negative images. More recently Perl et al. (2023) found that in an MRI, most memory retrieval lights up the hippocampus except emotionally intense memories light up the posterior cingulate cortex instead, where we assess current threats. We can physically see that some memories stick with us and behave as if they’re happening now and that working with them can decrease their effect on us.

From all the examples of what it might look like, the art of processing appears to be anything that gives some room to emotional experiences, possibly by merely bringing them into the light or finding connections to older experiences, challenging our older beliefs to develop new neural pathways with new belief systems, exhausting the memory when feeling the experience, developing empathy and compassion for what our younger self endured, or getting our parts to talk it out.

It’s a bit of work, but instead of compulsively attending to our inner crap by ruminating and then escaping the discomfort by scrolling online, the theory suggests that an active investigation can reduce that badgering from our brain. We’re only unburdened longterm by opening it up. I like this factory metaphor: Our old emotions sit in boxes on a conveyor belt. If we get sidetracked and ignore them, they just come around again later. We have to take the box off the conveyor and open it up to see what’s inside. We’re unlikely to completely clear off the conveyor belt, but we can definitely reduce the number of boxes coming round and round at us.

Looking inward is not a self-absorbed hobby, nor is it an analgesic to calm us in the midst of so many tragedies. This turn toward the self may be able to help us quiet the noise enough to better think and to muster a useful reaction when we are failed by governments and other leaders, whether around Covid, climate change, or conflicts. It appears necessary to find our better nature in order to reduce polarization in our societies and to tap into our common humanity to forge a better path