by David Greer

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

To the best of my knowledge, R has never owned a boat. No canoe or coracle, not a dinghy or dory, nor even a yacht. His abiding passion has always been small planes, especially the four-seat Beech Bonanza he likes to fly to tiny airstrips scattered about the continent, which serve in turn as starting points for terrestrial excursions (folding bicycle) to the back of beyond with his lady love, B.

So why boathouses?

“Well,” said R, “I love the light of the water reflecting on the walls and ceiling of the boathouse. And it’s hard to imagine a more relaxing sound than the gentle lapping of waves against a boathouse slip. It’s a sound that accentuates the pleasure of writing or reading or simple conversation. If you’re inclined to nap, as one does on holiday, there’s nothing more conducive to drifting off to sleep, and then you have the pleasure of a gentle awakening to a charming view of lake or ocean. All nicely framed by the boathouse doors.”

All of which explains why R and B, on their forthcoming trip to Austria to ride motorcycles on winding mountain roads, plan to rent a lake boathouse (mod cons included) as their base. It will be a peaceful counterpoint to the frenetic ecstasy of navigating the “twisties”, as they call the alpine hairpin turns.

Once upon a time, boathouses were simple affairs, erected for the sole purpose of providing safe haven to boats, the kind operated by sweep of arm and sweat of brow. As with all things simple, times changed. Complexities ensued. The two-stroke engine was invented, so boathouses expanded to accommodate motorboats. Motorboats got bigger, and boathouses got larger still. That gave someone the notion to take advantage of the swelling footprint and add a second storey with a bedroom or two, maybe throw in a bathroom, above the boat slips, to the point that many lakeshore boathouses today are more guesthouse than boathouse.

One result of that evolution is that boathouses have become an unlikely flashpoint for conflict in once peaceable lakeshore communities between two increasingly vocal groups. One consists of people who may have bought cottages years or decades ago as a retreat from the city, a place where they could enjoy natural views, listen to the loons calling in the morning mist, and enjoy peace and quiet. The smaller but more visible group has money to burn and little appreciation of nature other than as an impressive backdrop for an architect-designed cottage-mansion.

The vessel of choice of the former group might be an Old Town canoe, silently paddled so as not to disturb the kingfisher swooping to skewer trout minnows hovering in the shade of cedar branches overhanging the lake water. The cottage-mansion crowd tends to favour 300 hp Mercs and personal watercraft such as jet skis that generate a buzz. Their response to members of the first group who question the size of new boathouses and speed and noise of boats and ask for a little neighbourly consideration might best be characterized as a collective shrug. Respect for community character? Protection of fragile marine ecosystems? Not our problem. Besides, it’s a free country, isn’t it?

The fact that environmental impacts of the new breed of boats are out of sight and out of mind doesn’t make them any less real. One summer day this year on a small island on a southern Ontario lake, I was following the path of loon parents and their fledgling swimming close to shore when their calls were suddenly and completely obliterated by the roar of a flotilla of jet skis close enough for their wakes to swamp a shoreline loon nest in an instant and destroy its eggs. Also, because loons are diving birds and not easily seen, they’re vulnerable to strikes by quickly moving boats. While loon populations are generally stable in Canada, a marked decline in their ability to raise chicks to adulthood has been noted in recent years.

Loons are an obvious example to cite because they’re such an iconic species across northern North America. More generally, boat wakes can erode shorelines and disrupt habitat, while riprap and piers installed in conjunction with boathouses can disrupt natural flows, increase sedimentation and turbidity, and degrade the riparian areas that form the critical foundation for the food web on which all of a lake’s species depend.

The conflict over boathouses and speeding boats feels like a microcosm of the growing polarization sweeping the land these days. Fifty years ago, responding to demands for environmental protection triggered in large part by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Richard Nixon signed into law the first Endangered Species Act and Clean Air Act in the U.S. before his humiliating resignation. Fast forward a half century and we appear to be entering a new age of entitlement in which narrow self-interest trumps community well-being and environmental protection regulations are perceived more as nuisance than as necessity. Political priorities are an ever-swinging pendulum, of course, and fifty years hence we might find ourselves in an era when nations have acted decisively to mitigate climate change, conserve biodiversity, and address global poverty, even if a little too late. In the meantime, it’s small comfort to know that nature bats last.

The polarization of views about boathouses and boats has led to widely varying approaches to regulation. Some lakes take a laissez-faire approach to boating traffic while others prohibit all motorized vessels. On one southern Ontario lake, one local government placed no restriction on style or size of new boathouses while its neighbor banned them altogether. Meanwhile, libertarian scofflaws have been experimenting with creative approaches to skirt local regulations, like the claim by an Ontario man that his gigantic boathouse on Lake Rosseau was in fact an aerodrome intended to house a plane and therefore beyond the jurisdiction of local authorities. The court to which he appealed didn’t buy it, noting that he neither owned a plane nor possessed a pilot’s licence, and ordered him to remove his boathouse cum aerodrome forthwith.

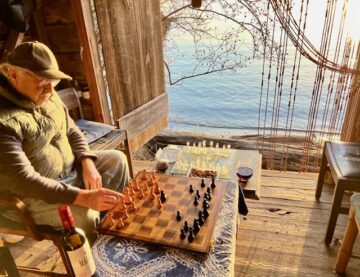

I’m as fond of boathouses as my friend R, though my taste leans more towards the simple old-fashioned kind, such as one that sits on the bank above a beach a few minutes’ walk from my cabin on an island on the Salish Sea on the Pacific coast. This tiny boathouse dates from a time long before motorboats became common in these waters, when settlers on the Gulf Islands would routinely row several miles to a much larger island (Vancouver Island) for supplies. On their return, the wooden, clinker-built rowboat would be dragged up the beach from tideline along a pair of planks, then winched into the tidy boathouse for storage until the next trip. Many boat owners of that era laid down a pair of steel rails from railroads to guide their rowboats up the beach, and their rusted remains can still be seen along many west coast beaches. Today the rowboat is long gone but the boathouse abides, a beloved neighborhood gathering place. Passersby on the beach below note the permanent presence of the chess board at the open entrance, ever ready for a friendly match. When the knights aren’t jousting with the bishops, the locals convene here for pre-dinner appies and wine and solve the problems of the world while keeping a watchful eye for the orcas and humpback whales that periodically pass close to shore.

Today the rowboat is long gone but the boathouse abides, a beloved neighborhood gathering place. Passersby on the beach below note the permanent presence of the chess board at the open entrance, ever ready for a friendly match. When the knights aren’t jousting with the bishops, the locals convene here for pre-dinner appies and wine and solve the problems of the world while keeping a watchful eye for the orcas and humpback whales that periodically pass close to shore.

Humpbacks are the gentle giants of the cetacean community, breeding in Mexican and Hawaiian waters in the winter and then moving north up the Pacific coast with their calves to feed on tiny krill through the summer months. Hundreds gather in the relatively calm waters of the Salish Sea every year. Humpbacks are pipsqueaks compared to the blue whale, merely 40 or 50 feet long, but nevertheless mighty impressive when they breach and spout near the shore or surface beside one’s kayak, revealing a curious eye the size of a grapefruit before subsiding back into the depths like some black volcanic island.

This being an oceanic rather than a lake boathouse, the ethereal calls of loons are replaced by the shrieks of seagulls and barking of seals and occasional bursts of whale breath. Farther out to sea, along the horizon across the international border, lie the nearest of the American San Juan Islands. If you were to sit in the boathouse on the evening of July 4th, you might watch the southern sky bloom with fireworks bursts over Orcas and San Juan and Lopez, silent but eerily beautiful from your vantage point miles away.

I have no boathouse on my own nearby property. My little plot of land lies a couple of hundred yards inland. I can still feel the vibration in the ground of the giant freighters fighting the tides through Haro Strait, but I can’t see them. What I have instead is an outhouse, far less glamorous than a boathouse but with its own humble merits deserving of fond recognition when nature calls or even when it’s mute.

Like the boathouse, my outhouse rises to the occasion when needed and requires little maintenance. It needs no tools for its employment other than a few bits of paper and a metal scoop to scatter woodstove ashes down the hole after each use. Every now and then its floor rots out (this being a rainforest) and has to be replaced to avoid the unexpected and rapid descent of an unwary occupant into the slough of despond, but it bravely carries on once repairs are made. Its door looks out not onto the ocean but instead onto a sea of ferns and firs and cedars.

The presence of my outhouse might seem superfluous since I had an actual bathroom installed years ago, complete with reglazed clawfoot bathtub, faux marble vanity and Toto flush toilet. Why would anyone want to stumble out to an outhouse in the woods with such mod cons so close to hand? Well, for starters, one might want to do so during one of the island’s predictable winter power outages that knock out the well, which relies on an electric pump to deliver water to the cabin. When I saved the outhouse during cabin renos, I did so for that specific eventuality, but was later surprised at how many of my visitors would make a beeline, insofar as beelines are feasible across a forest floor overgrown with salal and salmonberry, for the distant outhouse, there to perch like Rodin’s Thinker, gazing wistfully and at length upon the forest primeval beyond the open door.

If the outhouse was the only option, guests might not find it so attractive, but when there’s a choice between outhouse and flush toilet, the outhouse appears to wield a certain magical pull on anyone not prone to arachnophobia. There’s a psychological explanation for that, I assume. Maybe something to do with walking in the shoes of our great-grandparents, so to speak. Maybe there’s also a psychological explanation for the perverse virtue I feel, when the power is well and truly out, of lowering myself onto an ice-flecked toilet seat in the dark of night.

In truth, that pleasure can’t hold a candle to the elation I once experienced in a northern Alberta outhouse at thirty below when, expecting to descend onto something akin to a block of ice, I instead came to rest on, of all things, a Styrofoam toilet seat that so defied expectations in the comforting warmth afforded (or so it seemed) that I lingered far longer than strictly required. Yet another example of necessity being the mother of invention.

If there’s an outhouse equivalent of the five-star boathouses that are becoming increasingly prevalent, I can’t think what it might be. A five-hole outhouse with a bunk above? It’s pretty hard to improve on perfection, outhousewise, from a traditional one-seater with no attached apartment or built-in stone fireplace.

But then, it’s all relative, isn’t it? What seems primitive to westerners may be luxury in the eyes of others. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), roughly 60 percent of the world’s population, or around 4.5 billion people, either have no toilet at home or one that doesn’t safely manage human waste. Nearly 900 million people still practice open defecation—in fields, forests, open bodies of water or other open space. When I was travelling in India, there were several occasions on which I found myself obliged to squat over a hole in the floor with no supports and with my creaking knees protesting all the while, but at least it was a nominal toilet with four walls around it.

Passing through Delhi, I lunched with Bindeshwar Pathak, who then took me on a tour of his toilet museum, in which the displays portray the evolution of sanitation practices throughout human history. Dr. Pathak devoted his life to promoting and implementing improved sanitation and hygiene in rural India, designing a two-pit pour-flush composting toilet, using barely more than a litre of water, that served the dual purpose of improving sanitation and generating fertilizer for crops, and then founding Sulabh International Social Service Organisation to, among other purposes, make the toilet available to millions of households. The toilet museum was intended to raise the awareness of visitors to the dire state of sanitation in much of the country and to generate support for the efforts of Sulabh International.

One of the more bizarre exhibits at the toilet museum is a replica of the throne within a throne employed by Louis XIV to enable him to hold court without the inconvenience of relocating elsewhere to relieve himself—a throne with a built-in port-a-potty. (“Throne” as a modern euphemism for “toilet” derives from the time when only royalty had access to portable toilets in palaces, though the Sun King may have been the first crowned head to so efficiently combine the two types of throne in one.) Heads of state these days are generally not inclined to embrace the levels of excess displayed by Louis XIV, though a modern American president’s fondness for extravagances such as a golden escalator once inspired the Guggenheim Museum to offer to install artist Maurizio Cattelan’s fully functional 18-karat gold toilet in the White House.

It’s tempting to picture either of the above worthies enjoying the view of the rainforest from my outhouse. Frankly, I doubt it would be their cup of tea. Certainly Louis never had to deal with the consequences of a power outage, and if the president did, well, there were minions standing by to leap into action.

I’d rather picture them together in the boathouse down the beach, perhaps on opposite sides of the chess board lamenting the unfairness of queens being assigned more power than kings. Better still, I imagine them hunched over their separate appie trays, one perhaps featuring escargots à la Bourguignonne and the other Big Mac mini-sliders, exchanging tall tales and finding common ground in ridiculing the English. Since I control the fantasy, it concludes with a giant humpback whale breaching close to shore, dumbfounding and humbling king and president alike as they gaze in openmouthed awe at the real McCoy, a being truly majestic in nature and form.