by Jeroen van Baar

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

In recent years, scientists have started to uncover how this ‘gut microbiome’ shapes a variety of health outcomes including obesity and depression. For instance, when researchers transplanted fecal matter from depressed humans to rats, those rats started showing signs of depression themselves. We’re still unsure why this happens—it could have to do with the production of neurotransmitters, which depends on how food is processed—but the gut microbiome forms a promising horizon of health science.

This has raised the obvious question why the biome in your belly looks the way it does. Where did it come from? We normally assume that the microbiome is mostly shaped by the food we eat. But a new Nature study provides a radical refinement of this story: our social interactions can shape the microbial communities living inside us.

The study involved mapping the social networks and sequencing the microbiomes of 1,787 adults in 18 isolated villages in Honduras. Participants were asked to self-collect stool samples, which were stored in liquid nitrogen and shipped to the USA for analysis. A detailed survey and photographic census helped participants identify their social connections, including their friends and family.

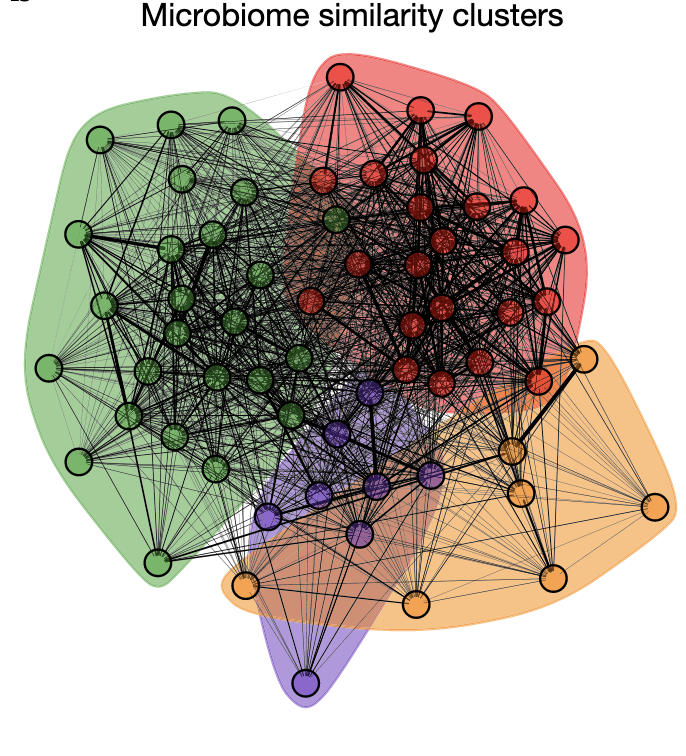

Analyzing the data, the research team found that the gut microbiome looked the most similar between members of the same household: they shared up to 14% of the microbial strains in their guts. However, even friends who see each other regularly shared about 8% of strains, while strangers from the same village shared only 4%. Microbiome similarity even extended to friends of friends, forming potential transmission chains that spread strains within communities.

Although the role of shared environment cannot be ruled out, the study strongly suggests that we pass our microbiome to one another in a literal sense. Social connection was a stronger indicator of microbiome similarity than similarity in diet, medication use, or socio-demographic attributes. And physical proximity, such as when sharing a meal, was predictive of microbiome similarity beyond just connection status.

Nicholas Christakis, the senior author of the study, has long been a leading voice in epidemiology and data science, investigating how diseases are distributed in social networks. Some of his most famous work concerns diseases we generally consider not to be communicable. In a famous 2011 paper, for instance, his team showed that friends of depressed folks are more likely to be depressed themselves, and that this apparent ‘contagion’ effect extended even to one’s friends’ friends’ friends. It has always been an open question why or how that may be happening.

Writing on BlueSky, Christakis is justifiably excited about the answer his new paper puts forward. ‘This work has implications for a radical idea: diseases formerly thought to be biologically non-communicable (e.g., obesity, depression, hypertension, arthritis, etc.) may actually be (somewhat!) communicable, via the spread of the microbiome.’

The paper thus has potentially far-reaching implications for how we think about sickness and health. Insofar as our microbiome helps us fend off disease, the study is a reminder of the importance of face-to-face social connection. It also suggests that the clustering of health outcomes (good or bad) within social strata may result from more than just structural oppression. If you can catch healthy sets of microbes from healthy people, and unhealthy ones from unhealthy ones, then the microbiome may form a feedback loop that keeps health inequities in place between social groups.

The most intriguing interpretation, though, is a hopeful one. If a diverse microbiome is good for your health, we may be able to boost our well-being by simply breaking bread with people we don’t know. That is a wonderful message to take into the upcoming holiday season. Happy Thanksgiving!

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.