by Steve Szilagyi

Andreas Grüntzig’s plane blew a 38-foot-wide crater in the Georgia dirt where it crashed. Investigators needed several days to collect and identify the remains of the famous physician, his second wife, Margaret, and their two Irish setters, Gin and Tonic. People who write about Grüntzig after his death compare him to a shooting star, a comet, or the incautiously winged Icarus. This is to be expected when the subject is a high-flying medical hero who dies hitting the earth at an estimated 300 miles per hour.

The journal Cardiology called Grüntzig “the father of modern cardiology.” His story is told in engrossing detail in David Monagan’s book Journey into the Heart, whose introduction declares, “Grüntzig, once derided as another charlatan, changed the course of medicine … His work inspired an arc of discovery that has never stopped rising.”

Grüntzig invented balloon angioplasty, today one of the most commonly performed complex medical procedures. The technique has been adapted for use throughout the body, but its marquee application is the treatment of coronary artery disease, a leading cause of death and disability worldwide.

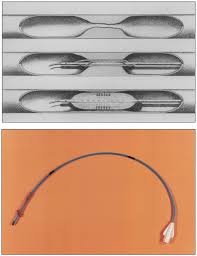

Balloon angioplasty is not an obvious idea. A catheter (thin, flexible wire) with a small, deflated balloon at its tip is inserted into the target artery and guided to the site of the blockage. Once in place, the balloon is inflated, compressing the plaque against the artery walls and restoring blood flow.

If not for Grüntzig, there is no guarantee balloon angioplasty would ever have happened. He alone, it seems, had the vision to imagine the device, the diligence to build it, and most crucially, the power of personality to win over a hostile and skeptical medical world.

Kitchen table crew. Andreas Grüntzig was born in Dresden in 1939. His mother was a piano teacher. His father disappeared in the Battle of Berlin. Andreas escaped East Germany in 1959 and made his way to Heidelberg. There he studied medicine. He was a brilliant student and went on to qualify in internal medicine, cardiology, and public health.

His career took him to Switzerland, where he eventually joined the cardiology department of Zurich University Hospital. “Why,” a patient once asked him, “can’t doctors scrub out a blocked artery the way a plumber scrubs out a blocked pipe?” That remark, he once said, was the inspiration for his breakthrough.

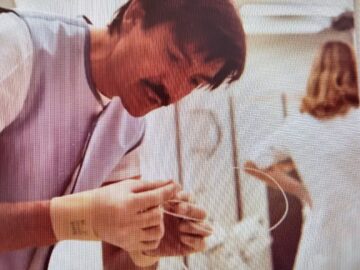

Andreas and his wife Michaela lived in a tiny apartment in Zurich. Many nights, after a full day of work, Andreas, Michaela, and Andreas’ assistant, Maria Schlumph, gathered around their kitchen table, where they designed and crafted iterative prototypes for what was to become the angioplasty balloon. (Andreas’ generously shared credit with the women in after years.)

In the beginning, every version of the balloon catheter was built by hand at this table. Andreas tested it on dogs and human cadavers. In 1974, he performed the first balloon angioplasty on a live patient, opening a narrowed femoral artery in the leg. He went on to successfully treat 800 patients with leg occlusions over the next three years. Only then did he feel confident enough to ask the hospital for permission to perform his procedure on a patient’s heart.

The prototype (bottom) and how it works.

They came to scoff. Andreas was young. He did not rank high in the hospital pecking order. His procedure threatened some established interests, especially the hospital’s cardiac surgeons. Balloon angioplasty was explicitly offered as an alternative to coronary artery bypass surgery. The surgeons warned—not unreasonably—that the catheter might puncture the blood vessel, that it might trigger a heart attack or stroke. One hospital administrator later admitted that they were afraid that if Andreas’ procedure killed a patient, they’d all go to jail.

Andreas eventually managed to get the in-hospital support he needed to go ahead against the objections of his higher-ups. The first balloon angioplasty was a total success. Next, Andreas needed to convince the world that it worked. Supported by strong clinical evidence, he embarked on a now-legendary series of lectures, seminars, and training sessions.

The cardiological establishment came to scoff, as they say, but stayed to pray—and to party. Andreas loved a good bash. His hard-nosed training sessions were always followed by memorably hard-drinking celebrations in exotic locales. This pattern might have reflected Andreas’ inner dynamics, where the intense care and focus required by his clinical work needed be followed by some kind of exuberant, even transgressive, release.

Partying and teaching, Andreas won over a coterie of supporters, the Brotherhood of the Balloon. One of the “brothers” recalled working with Andreas as “the most electrifying experience of my life.” The procedure caught on across Europe and America, driven by Andreas’ charismatic presentations and the zeal of his acolytes.

Gold rush. Millions of dollars came into play as hospitals worldwide rushed to upgrade their facilities and equipment to offer the new procedure. Device manufacturers scrambled to get in on the gold rush. Copycats entered the field. Executives selling a rival balloon device went to jail for hiding the fact that their inferior product was killing patients. Insurance companies revised their policies and payouts. Andreas and his device stirred up clinical controversies across the full range of cardiovascular specialties, some of which persist to this day.

Meanwhile, back at Zurich University Hospital, the hidebound administration tightened their restrictions around Andreas and his procedure. Despite worldwide fame, he was moved to a windowless office in a sub-basement. As one newspaper put it, “Instead of treating him like a hero, his bosses bullied him.” (One of these obstructive administrators later tried to claim co-credit for Andreas’ triumph.)

It wasn’t hard for Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, to lure him away in 1980. Flush with a $100 million grant from a Coca-Cola heir, Emory was establishing a new heart center on their posh, green campus. They not only offered Andreas an office with a window but five times more than he was making in Zurich—plus status, access to state-of-the-art facilities, and the freedom to work as hard as he wanted.

Andreas came to the United States with his wife Michaela and their young daughter. He bought a mansion in a high-falutin’ neighborhood and was quickly taken up by Atlanta’s usually hard-to-penetrate high society. Andreas adapted well to America. But in some ways, he was inveterately European, including in the matter of bathing costume. At posh pool parties or the beach, he loved strutting out in a tiny Speedo. Stuffy socialites raised their eyebrows, his friends joshed him, but no one seems to have complained. The man was really good looking.

Swooning. One female associate famously described him as “a combination of Clark Gable, Omar Sharif, and Errol Flynn rolled into one.” Another said of his many conquests, “It was easy for him. Every woman just swooned. You couldn’t help it.” Swooning is no mere figure of speech here: One young lady at Emory sought medical help for chronic fainting in his presence. “Some women just threw their clothes off at the sight of him,” observed the wife of a close friend.

By all accounts, Andreas made the most of his opportunities, having left behind a string of broken hearts in Europe. Even male colleagues were dazzled by Andreas’ good looks, charisma, and John F. Kennedy-like aura. They did not laugh when he told them he expected someday to get the Nobel Prize (he was nominated), and their long-after recollections rarely fail to mention his appearance and incredible charm.

“Everyone who knew him realized he was unique,” recalled close friend and colleague Willis Hurst. Andreas had dash. He kissed women’s hands. Procedure rooms lit up when he came through the door. It doesn’t sound like much, but no one forgot how he wore his hairnet rakishly off to one side, like a beret.

An empty house. Andreas’ wife Michaela put up with a lot. She was bored and underemployed in Atlanta. She quietly despised American materialism. In a kind of symbolic protest, she left the Atlanta house unfurnished. Friends remember parties where everyone had to sit on the floor. Meanwhile, Andreas was flaunting his affairs virtually under her nose—especially that with a much younger graduate student named Margaret Ann Thornton.

Andreas, of course, chided those who disapproved. Didn’t they know that Europeans were more open-minded about infidelity? “Marriage is just a convenience,” he told a friend. Michaela was supposed to be okay with it all—until she wasn’t and moved back to Zurich. The couple divorced and Andreas quickly married Margaret, who looked as good in a tiny bathing suit as he did.

A downward arc. Author David Monagan fully and sympathetically describes Andreas’ decline in Journey Into the Heart. There are stories of drunk driving, uncharacteristic bad temper, and crude butt-grabbing. Yet Andreas remained a conscientious physician to the end. His often-noted empathy for patients and concern for their safety never wavered. When he lost his first patient in 1984, he was emotionally crushed.

All across the world, his procedure was curtailing the suffering of angina, the crippling chest pain caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart. Thousands of patients were being spared the chest-cracking ordeal of open heart surgery, with its general sense of having been hit by a truck. His disciples were taking his technique into new parts of the body, and pioneering the use of stents to hold the blood vessel open after being cleared.

At the same time, Andreas seemed lost and restless. He wanted to return to Europe and run his own department, but European hospitals weren’t eager to welcome disruptive superstars.

A lifelong flying enthusiast, Andreas purchased a one-engine Beechcraft Bonanza airplane in 1984. By all accounts, he was a competent pilot. The aircraft came in handy after he bought a getaway cottage on an island off the coast of Georgia. He could fly to the island on weekends and be back in the hospital by Monday.

But like Mr. Toad in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, Andreas was never satisfied with his transportation. He wanted the next fastest or most expensive model. Very soon, he traded in his single-engine plane for a twin-engine Piper Aerostar 601P. A flying friend recalled, “My blood ran cold,” when he’d heard what Andreas had bought. The friend knew that a plane that powerful needed an experienced pilot.

Uncertain skies. Visitors to the new Grüntzig household sensed that things weren’t well between Andreas and his younger wife. Both were drinking heavily. In April 1985, a tornado swept through their Atlanta neighborhood and heavily damaged their house. It was an inconvenience more than anything else—they had all the money in the world to repair the damage. But Mother Nature wasn’t through with them. Seven months later, Hurricane Juan blew up in the Gulf of Mexico.

With the hurricane raging well to the south of them, Andreas flew his wife and their two dogs to their island cottage on Friday, October 25. The next day, Andreas learned that one of his patients had taken a turn for the worse. He was eager to get back. The ocean was being lashed by the edges of the hurricane, and while conditions were rugged, planes were still flying. On Sunday, October 26, Andreas decided to risk it. Shortly before they left for the airfield, Margaret got a phone call. It was her mother, begging her not to let Andreas fly home that night. It’s not known whether Margaret relayed the message.

The couple and their dogs took off into the uncertain skies. They were never seen in one piece again. Investigators believe Andreas became disoriented in the clouds and lost track of which way was up or down.

The aftermath. Andreas’ brother, also a physician, believed it was murder. Naming no names and offering no proof, he hinted at dark conspiracies surrounding the money and power that came with Andreas’ rapid rise. Others dismissed these claims as grief-stricken speculation.

Whatever the cause, Andreas Grüntzig left behind a legacy that has enhanced existence for millions. His invention of balloon angioplasty expanded the ability of physicians to relieve pain and extend life. He proved how a single determined individual could shake up entrenched systems and – one way or another – make an impact on the world.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.