Monday Poem

by Jochen Szangolies

Humans, Plato famously held, are featherless bipeds: uniquely singled out from other animals by walking permanently on two legs, which delineates us against fish, mammals, and reptiles, while not sporting the sort of plumage associated with birds. Of course, he knew little of the mighty T. Rex (although its featherlessness is subject to recent academic dispute), and Diogenes the Cynic quickly came up with a deflationary argument: he crashed Plato’s school, brandishing a plucked chicken.

Plato was engaged in a project that goes on to this very day: the definition of what, exactly, is it that makes humans human—how we are distinguished from all else that creeps and crawls on the face of the Earth (and presumably, beyond). However, as performatively illustrated by Diogenes, such an endeavor is intrinsically fraught: defining the human is not just a matter of practicality, but what—or who—counts as human impinges on questions of moral standing, of whether to extend certain rights and protections. A standard human, if such a thing existed, would be a norm against which all are compared, and either permitted to enter ‘club human’ or not.

Even this is a simplification, however. The line, here, is not as clear as ‘human’ and ‘not human’—frequently, in the history of humanity, we encounter various categories of ‘human, but’: people that count as human, but not as the special sort of human, the ‘standard human’ that forms the measure of what it means to be truly worthy of all the rights and protections that society affords its most highly valued members.

This too is exemplified in the story of Plato’s featherless biped: what he was trying to define was man, not human. While we might count this as a quirk of a bygone time, or of the ancient Greek language, this attitude is pervasive throughout history, and finds its echo both in overt ostracism of ‘nonstandard humans’ and in subtle slanting of the playing field against those that don’t quite measure up. Read more »

by Thomas R. Wells

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has reminded everyone of how dangerous a world we live in. As rich countries scramble to rebuild militaries dismantled by post-Cold war complacency, one of the other problems of national success has become apparent: young people have better things to do than play soldier.

My solution: conscript the old instead

Armies have a recruitment problem: they can’t get enough healthy young men to join. Young men have traditionally been the best recruits for fighting wars. They can carry lots of equipment over long distances without getting too tired to fight afterwards. They generally lack a visceral awareness of their own mortality, so they can be ordered to do insanely dangerous things. Indeed, many of them rather enjoy the excitement, intense camaraderie, and sense of shared purpose that accompanies war-fighting, and the survivors look back on it fondly when they have grown old and boring. As only partially formed adults, young men conveniently also lack the self-confidence and resources to question orders and hierarchies.

Most crucially, until very recently young men have been cheap, plentiful and easily replaced. The death of an 18 year old man was no great loss to a pre-industrial society, since it didn’t represent any great stock of human capital. (It did represent a stock of muscle power, but subsistence economies were generally constrained by the available land rather than the labour supply to work it.) Fertility rates were high so lost men could easily be replaced as long as plenty of fertile women remained. Altogether then, the cost of using up vast numbers of young men’s lives in warfare was quite affordable and hence commonplace. (Archaeological estimates for male mortality rates by violence in the hunter-gatherer societies that my students like to romanticise range from a terrifying 5% to a scarcely imaginable 35%, and sometimes even higher – see e.g. the research summarised by Azar Gat.)

Young men are still the ideal recruits for war-fighting. But their lives are far more valuable than they used to be, thanks to demographic and economic changes over the last 200 years (the drivers and consequences of the rise of capitalism). Read more »

by Derek Neal

Have you ever read a book that you thought you were going to write? A book that captures something you’ve experienced and wanted to put into words, only to realize that someone else has already done it? The Apartment by Greg Baxter is that book for me.

Have you ever read a book that you thought you were going to write? A book that captures something you’ve experienced and wanted to put into words, only to realize that someone else has already done it? The Apartment by Greg Baxter is that book for me.

The Apartment was published in 2012 as Baxter’s debut novel and follows an unnamed American as he looks for an apartment over one day in a cold and snowy European city. Interspersed in his search are flashbacks to his home in America, his deployment in Iraq, and various encounters he’s had while living in Europe. He’s accompanied by Saskia, a local woman intent on helping him, as well as a few other characters they meet throughout the day. This is the extent of the plot.

I’ve thought about writing a story or a novel for years about an American in Europe. I wrote a short story based on an experience in Italy, submitted it to a competition, and promptly forgot about it. I’ve started multiple other stories based in Turin and Nice, France—both places I’ve lived—which are scattered throughout notebooks and Microsoft Word files. Sometimes these stories have plots; sometimes they don’t. What I’m more interested in is atmosphere and style. Baxter seems to have a similar approach. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Rebecca Baumgartner

The transformation of bringing a child into one’s family is conceptualized differently by different folks. It is rare, however, to encounter a parent who questions whether parenthood is any kind of transformation at all. This is the provocative stance taken by Anastasia Berg in her piece “What If Motherhood Isn’t Transformative at All?”

Berg is a philosophy professor at UC Irvine. She is also a mother who is very invested in not being changed by the experience of motherhood – or at least, in having us think that she is very invested in not being changed by the experience of motherhood.

The article purports to be about “the pitfalls of treating motherhood as a transformative identity,” but it’s not actually about those pitfalls at all. What it’s actually about is Berg’s reluctance to be a certain type of mother, and her insecurity about whether this necessarily makes her a bad mother. She doesn’t say this explicitly, mind you; this is a piece that presents the facade of vulnerability, while building an elaborate bastion against vulnerability with every sentence. Despite coming from an ostensibly feminist starting point, Berg puts forth a viewpoint that I find just as disingenuous, confining, and unsatisfying as the blanket dictum that parenthood should consume one’s life. Read more »

Voices Choir concert in Bozen, South Tyrol.

by Barbara Fischkin

I remember the day I realized that my cousin Bernard Moskowitz—my father’s nephew—was nothing like my other relatives.

The realization came in a flash as I spotted a newly arrived letter on the dining room table at our home at 4722 Avenue I in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. Two pages. Typewritten. It remains in my mind’s eye. I recognized the scratchy signature: It was my “Cousin Bernie.” I went back to the first page because that seemed like it was from somebody else It was embossed with these words:

Moorhead, Minnesota.

Professor B.B. Morris.

My mother, her eagle eyes in play, gazed through the opening from the kitchen and walked up behind me.

“Is this…,” I said

“Yes,” she replied, smiling. “Cousin Bernie got a good job. Daddy is so proud.” She paused. A worried look took over her face. “He changed his name. Maybe they don’t like Jews there.” Another pause. More worry. “It must be very cold.”

I imagined my mother sending Cousin Bernie a sweater. Or two. Or ten.

What else? A Star of David tie clip? A Hebrew prayer book? The possibilities were endless. Read more »

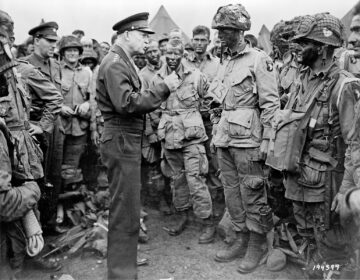

by Michael Liss

Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force! You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hope and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

—Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, June 6, 1944

We had to storm the beaches at Normandy. There was no other way. None, at least, to loosen Hitler’s death-grip on Western Europe. One by one, proud peoples saw their countries’ armies overwhelmed by Blitzkrieg conducted with a speed and agility that astonished.

First Poland, with Germany’s partner of convenience, the Russians, which then rampaged through Eastern Europe, gobbling up prizes. Then, after a pause for the so-called “Phony War,” the Germans moved on to Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg. May 13, 1940, they pivoted, sent their troops over the River Meuse, blasted and danced past the supposedly impenetrable Maginot Line, and induced the mass evacuation at Dunkirk. The French Army, it could be said the French country, was in full physical and moral retreat. By June 22, it was over. The French were forced into a humiliating armistice in the very railcar in which Germany had accepted defeat in World War I. Hitler literally danced a jig.

Germany occupied roughly three-fifths of European French territory, including the entire coastline across from the English Channel and the Atlantic. Britain had survived the desperate Battle of Britain but stood alone. The Italians joined the Axis to grab some of the spoils for themselves, and, in early 1941, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Romania followed. In April of that year, the Germans crushed Greece and Yugoslavia.

“Fortress Europe,” essentially a massive buffer zone for the Germans, ending in a fortified Atlantic coastline, became a reality. The Nazis built the Atlantic Wall, a 2,400-mile line of obstacles, including 6.5 million mines, thousands of concrete bunkers and pillboxes bristling with artillery, and countless tank traps. Where there wasn’t a wall, there were cliffs looking over the beaches where Allied forces were expected to land, and, from those cliffs, German soldiers were prepared to rain down fire. Read more »

by R. Passov

A few weeks back, I flew to Los Angeles for my 40th business school reunion. I went knowing it was going to be a hopeless affair. I was the odd man out forty years ago and remain so. I had stumbled into business school not out of some ambition to make a fortune on Wall Street, something I knew next to nothing about, but rather because I had stumbled onto a thin set of classes whereby one could get credit for just taking finals. I successfully employed that ruse across six years of undergraduate struggles to land a B.A. A significant number of those finals were taken in courses that constituted the first year of my MBA program. I completed my undergraduate studies on a Friday and started business school the following Monday.

I had no business being in business school. I lacked a rudimentary understanding of the business world. My only two significant sources of work experience were selling drugs and working in liquor stores.

I attacked business like a polished rube. I hit the books, blazing through my classes as though on an academic quest to Mt Olympus. While I went the extra mile solving differential equations to map product penetration rates, many of my classmates were at beer busts or “networking forever down Columbus Avenue.”

…I’ve seen them in commercials sailin’ boats and plain’ ball, Pourin’ beer for one another cryin’, “Why not have it all?” Now I saw the ghostly progress as the wind around me blew, Till I felt the urge to purchase a BMW

All the salad bars were empty, all the Quiche Lorraine was gone. I heard the yuppies crying as they vanished in the dawn. Calling brand names to each other, as they faded from my view. They’ll be networking forever down Columbus Avenue

—”Yuppies in the Sky”, Peter, Paul and Mary

So, why did I go to that reunion? I went because it’s rare to have the opportunity to follow the routes of so many lives across forty years. I also went because my cohorts and I swum in the currents of the Reagan revolution. We left B-school at the zenith of Regan’s influence. When the ‘Chicago Boys’, those now well-known, hard-charging, un-forgiving right-of-center academics were making much of the western world into a capitalistic democracy, where the ‘free market’ knows best. Read more »

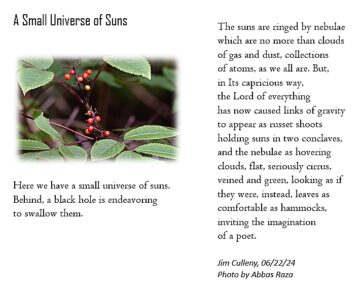

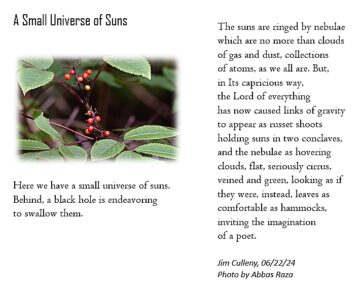

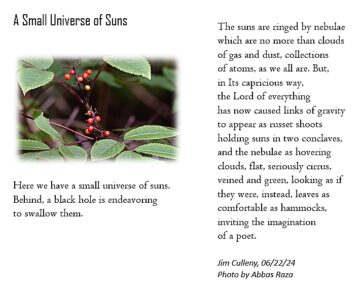

Here is this tree before me

whose skin is as fissured and split

as the landscape of the Rockies as if

a network of rivers had, for centuries,

by force of friction, sculpted canyons

into its surface; bark beaten by

torrents of rain, dried by torch of sun,

torn by whip of wind, but

remaining steadfast as Everest

despite every onslaught, for

well beyond what will be its

natural life, as it is

…. framed in this canvas,

…. or in the length of these lines,

…. or in the music of the spheres,

…. or in the dance of gypsies,

all meant to share with others

the strength and miracle

of its character.

Jim Culleny, 6/14/24

by Rafaël Newman

It was my birthday last month, a “round” one, as anniversaries ending in zero are known in Switzerland; and in gratitude for having made it to a veritably Sumerian age, as well as for the good health and happiness I am currently enjoying, I threw a large party for family and friends. Then, not quite one week later, I flew off to Albania, a land I have come to associate with the sensation and enactment of gratitude.

It was my birthday last month, a “round” one, as anniversaries ending in zero are known in Switzerland; and in gratitude for having made it to a veritably Sumerian age, as well as for the good health and happiness I am currently enjoying, I threw a large party for family and friends. Then, not quite one week later, I flew off to Albania, a land I have come to associate with the sensation and enactment of gratitude.

Albanians in official capacity are fond of giving each other elaborately worded certificates of gratitude, presented in velveteen dossiers at formal ceremonies. I know this because I have attended several of these ceremonies. I have even received such a certificate myself—for, although not a native of Shqipëria, I have now twice been invited to participate in Albanian cultural affairs.

The first occasion, in 2019, was a literary festival in Pejë, in northwest Kosovo, where I joined a host of poets from across the Balkan region and beyond to read poetry in memory of Azem Shkreli (1938-1997), a local man of letters. During the closing ceremony, surrounded on the stage of Pejë’s municipal theater by the many poets in attendance and congratulated by various Kosovar dignitaries, I was handed my certificate by the woman who had invited me to the festival, my friend Entela Kasi, president of the Albanian PEN Centre. Read more »

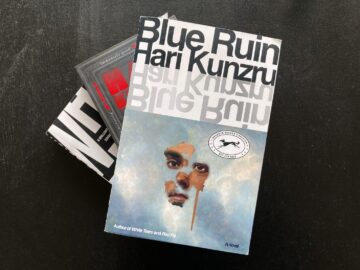

by Claire Chambers

Introduction

Introduction

Hari Kunzru has recently completed the third novel in his three colours trilogy about race, class, and the arts. White Tears concerns music and was published in 2017. Red Pill deals with literature and came out in 2020. And Blue Ruin zeroes in on fine art, having just been released last month, in May 2024. All of the novels examine racism and evoke various upheavals in the present moment. The titles of this tripartite sequence of novels figure forth the American or British flag, signifying the fractured state of these nations. Paul Gilroy rightly claimed in the title of his 1987 book that ‘There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack’, and Kunzru’s storyworld also highlights the strife amid the stars and stripes.

In this essay, I am interested in how a sensory studies perspective can enrich discussions of Kunzru’s trilogy. I discuss sound (and, to a lesser extent, touch or its absence) and a need to listen to other voices. The key issue here is whether, and to what extent, the tolerant should be tolerant of the intolerant. In White Tears, Red Pill, and Blue Ruin, Kunzru makes a conscious effort to listen to the repugnant politics of white supremacists, alt-right provocateurs, and QAnon or ‘plandemic’ conspiracy theorists. Trying to understand their views without either endorsing or criticizing them (while subtly forming judgements), Kunzru trains his ear on loathsome conversations and does some radical listening. Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

All I wanted, I told him, was “the perfect teapot.” Just one would be enough, I said, but it had to be perfect (1) — as if a teapot could make everything else in the world okay. A seemingly simple task, and yet finding it was elusive as any great chase.

My first demand was it had to be a Yixing zisha teapot. Valued since at least the tenth century in China, zisha pots are purple or reddish-brownish, unglazed stoneware that are so beautiful they will make you drool (2). The first thing I did was spend hours at the Flagstaff Tea Museum in Hong Kong. Studying the pots in their collection, I tried to narrow down exactly what I wanted in my own “perfect pot.” I learned all about the way zisha pots are hand-modeled out of what is extremely hard clay. Like any great Literati art, one artist alone is traditionally in charge of the entire process from start to finish, and therefore the artist’s seal will be affixed to the bottom of the pot as it is in every way that artist’s creation: one of a kind.

It was in Hong Kong where I’d first fallen in love with tea and stoneware pots. Even now, I never cease to marvel at how soft and warm stoneware feels in comparison to porcelain. Handling unglazed pottery is always a very sensual experience; porous and velvety, it’s like human skin. One of the reasons zisha pots are favored by Chinese tea masters is because the clay absorbs the fragrance and taste of the tea and over time the pot brings something of itself to every brewing, like antique oak barrels used for wine or the ground used in certain kinds of pickling. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

The turn of the 21st century saw a burst of atheistic declarations and critiques in the United States and Great Britain, led by a small group of celebrity atheists including Philosopher Daniel Dennett, Biologist Richard Dawkins, and journalist Christopher Hitchens. I have always found this New Atheism, as the movement is often called, to be a mixed bag. It was long overdue, and many good (if obvious) points were made. However, there was also a fair bit of navel-gazing and even stupidity. And among some of the celebrity leaders, I believe, there was also a profound misunderstanding of religion, how it functions, and even its basic purposes.

The turn of the 21st century saw a burst of atheistic declarations and critiques in the United States and Great Britain, led by a small group of celebrity atheists including Philosopher Daniel Dennett, Biologist Richard Dawkins, and journalist Christopher Hitchens. I have always found this New Atheism, as the movement is often called, to be a mixed bag. It was long overdue, and many good (if obvious) points were made. However, there was also a fair bit of navel-gazing and even stupidity. And among some of the celebrity leaders, I believe, there was also a profound misunderstanding of religion, how it functions, and even its basic purposes.Below I identify what I see as two basic recurring problems in modern atheism. I then offer two approaches that I believe atheists should consider for understanding and relating to the religious.

Problem 1: Arrogance. Don’t be so sure of yourself. Even if you’re not laboring under a “God delusion,” you should still have the humility to recognize that you know next to nothing, and what few answers you might proffer aren’t anything anyone wants to hear. If humanism is to offer any benefits, it must begin with an acknowledgment of humanity’s vast ignorance and inability to learn much.

This sentiment will likely send some admirers of science into paroxysms. Surely, they protest, we’ve learned so much over the last century or two. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Marie Snyder

A little learning is a dang’rous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

~ Alexander Pope

Is it, though?

We’re in a mental health crisis and people need more access to help. How much learning is necessary to help one another, and is it dangerous to listen and offer another perspective or even some suggestions without an advanced psych degree? In old movies, people told their stories to bartenders, hairstylists, or cab drivers for the price of a beer or trim or trip to the airport. They just needed a captive audience willing to listen to their worries Now we want people with credentials as if that will provide more certain results.

But not all credentials are created equal.

Last year BetterHelp got in the news for allegedly sharing confidential health data to social media sites, and was fined $7.8 million. TV writer Mike Drucker wrote:

“EVERY BETTERHELP AD: ‘We’re like therapy but cheaper and easier! We have people for every problem so you get care just for you!’

ACTUAL BETTERHELP: ‘We’re going to set you up with a confused therapist that will ghost after two sessions. Also we told Facebook about your assault.'”

More recently, the New York Times had an article on scams in the wellness coaching industry, describing scenarios in which the new recruits were bilked out of massive amounts for “tuition” made up of a few hours of videos, and then were never helped to find clients. Read more »

by David Winner

Throughout most of my life, I periodically napped in the back sitting room of my parent’s house in Charlottesville, gazing at an enormous shelf of my father’s books.

Throughout most of my life, I periodically napped in the back sitting room of my parent’s house in Charlottesville, gazing at an enormous shelf of my father’s books.

Why I am a Jew was an unlikely title to find. Though my father was most certainly a Jew, he was fiercely disconnected from all things Jewish. He claimed that he only learned that he was Jewish after he left his Jewish mother and Irish American stepfather behind in Pasadena to go to a very antisemitic Harvard in the late forties. He hated Woody Allen, Larry David, Bernie Sanders, and all other public Jews, never set foot in a synagogue or at a seder dinner, and was skeptical about the state of Israel.

Perhaps being brought up by such a non-Jewish Jew has influenced my perspective. When the news broke about the Hamas attacks in the fall, Angela, my wife, was cross with me before I even opened my mouth because she was stunned by what had happened and feared what I would say. I’ve had a long history of disparaging Israel.

A few days after the attacks, I came back to my house in Brooklyn to find Angela in conversation with our ultra-orthodox Jewish neighbors. They were in shock. Their seventeen-year-old son told us that Muslims had slated the following day for killing Jews around the world. Only Israel could protect us from the “animals.” The world, as he framed it, was overrun by an evil force out to get him and his community. Rather than confront his racism, I retreated inside. I didn’t think he would ever construct things any differently. Read more »