by Ethan Seavey

I’ve heard owls are signs of a big shift in your life; I also know that I only really look for owls during those times.

I’ve heard owls are signs of a big shift in your life; I also know that I only really look for owls during those times.

Exercise for me is short lived or long lived, short lived to match my attention or long lived to accommodate my frequent breaks for walking, exploring, writing, texting.

I’m running through the gulch and looking at the trees where the owl usually sits in the morning. It’s not morning really anymore. The sun is big in the sky and the owl is nowhere to be seen. I think to see the owl and to prove the shift in my life I’d need to wake up earlier.

After running out of the woods I follow the sidewalk to the water front and walk along that for a while. I see seagulls approach an old man who is bemused that they’ve identified him as a possible food source.

I walk down a pier for a while. It’s meant for fishing but it’s too early in the season for fishing so I don’t see anybody reeling in anything, and I’m looking for marvelous life-changing marlins. I watch a couple kiss on the other side of the pier. They point off into the distance at a warship.

As I run back to the woods, I have the thought that I don’t need to see an animal to decide I’m going through a life shift. That’s when I notice a globe in the water. Read more »

The

The  Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.

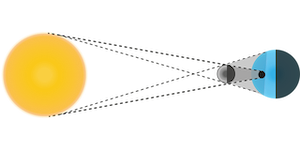

Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.  There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

Sughra Raza. Figure in Environment, May 1974.

Sughra Raza. Figure in Environment, May 1974.

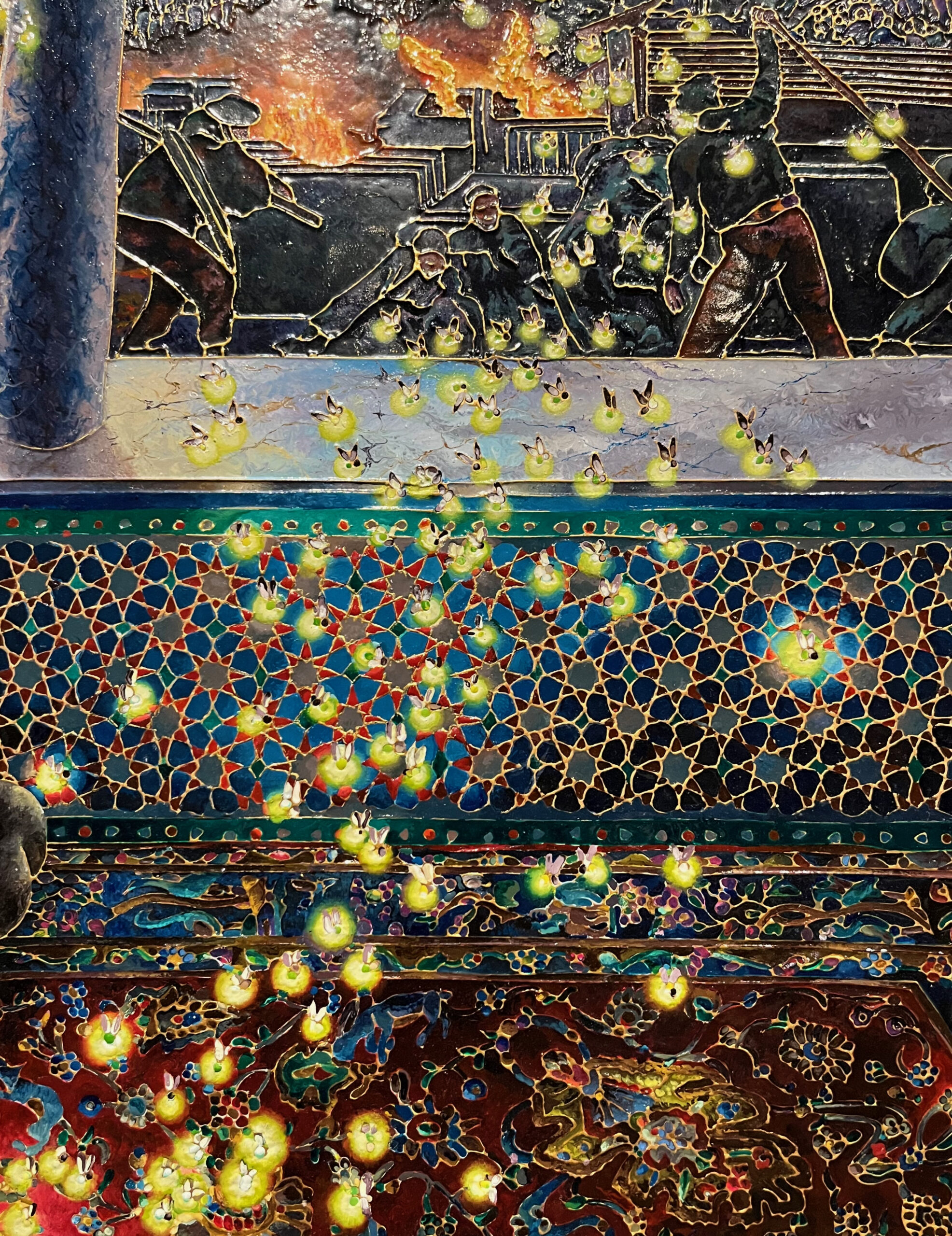

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)