by Derek Neal

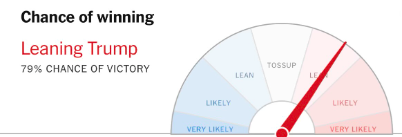

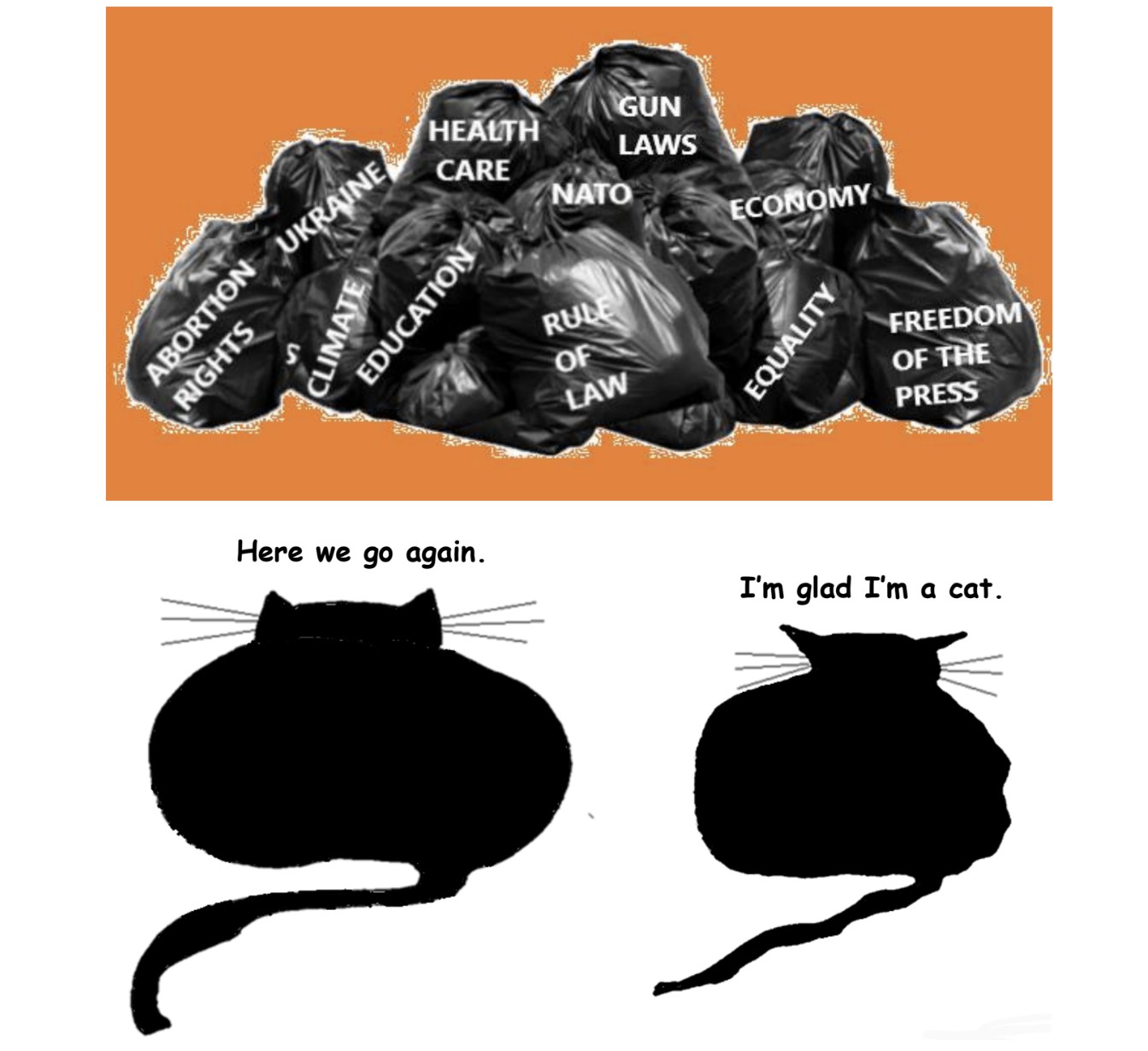

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election.

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election.

Over the course of my two and half hours at the bar, I ended up in conversation with three different men. M. was the man to my right. I’m normally not much of a talker, but the election provided an easy conversation starter. “Are you following the election?” I asked him. It was loud and I had to repeat my question. M. mumbled that he wasn’t but asked how it was going. “Looks like Trump might win,” I said. M. raised his eyebrows, which were flecked with grey, and said something along the lines of, “Well, he has some ideas.” I had trouble making out what M. was saying, partly because of the noise in the bar, but also because M. spoke so softly. It was as if he didn’t believe in the importance of his own words. Talking or not talking, it didn’t seem to matter to him.

I pulled out my phone again. Trump was at 82%. I showed M. Then he took out his phone, a flip phone. “I’ve still got this old thing,” he mumbled. This seemed like an opening for a new conversation—a discussion on the merits of “dumb” phones versus smartphones, on phone addiction, on attention. “Why’d you get one of those?” I asked M., gesturing at his phone. He looked away and started talking about privacy with smartphones, and how he didn’t want people tracking him, or something along those lines. “How do you like the flip phone? How long have you had it?” I asked. M. said he’d had it since 2016, and that it didn’t cause him any problems because he didn’t have a job, but it sure made meeting women difficult. Read more »

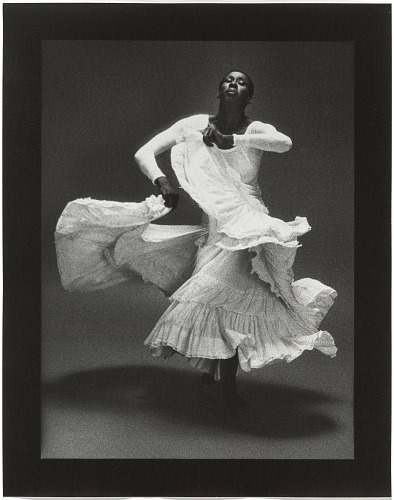

Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

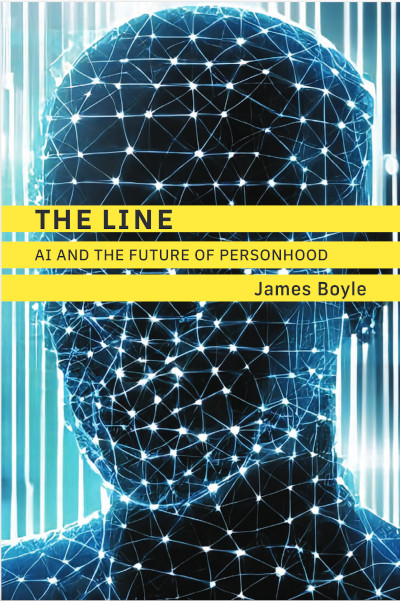

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

I dipped my toe into

I dipped my toe into  Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

by William Benzon

by William Benzon Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

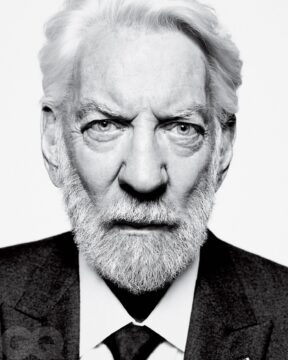

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.