by Martin Butler

Fewer than half the population in the UK believe in God according to the latest surveys, even though religious belief is growing globally and the heady days when the ‘new atheists’ were in full flight are now behind us. The internet has given those on opposite sides of the fence the opportunity to lock horns continually, each side determined to show the irrationality if not downright stupidity of their opponents. I wouldn’t expect the level of debate to be particularly high, but what I do find slightly depressing is the complete absence of anything but the crudest understanding of what belief in God and religious belief in general actually means. Both sides mostly embrace the ‘God of the gaps’ theory – science cannot explain everything, runs the argument, and God serves as a kind of backstop to account for the unexplained.

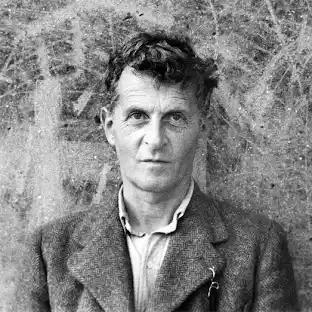

Ludwig Wittgenstein, one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century can, I think, help us to develop a more sophisticated conception of religious belief.[1] Despite never producing anything close to a philosophy of religion, the religious point of view was clearly important to him throughout his life: ‘I am not a religious man but I can’t help but seeing every problem from a religious point of view’ (RW p79). Although, Elizabeth Anscombe, a devout Catholic and one of his most famous pupils, once declared that ‘nobody understood Wittgenstein’s views on religion.’[2]

Wittgenstein famously produced two quite distinct approaches to philosophy, the first in the only book he published in his lifetime, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, and the second in the Philosophical Investigations, published posthumously; although there have been many other publications over the years of his extensive notebooks and conversations. Towards the end of the Tractatus several important remarks set the stage for his approach to religious belief through both periods of his philosophy. ‘We feel,’ he says, ‘that even when all possible scientific questions have been answered, the problems of life remain untouched’ (TLP 6.52).

It is with these ‘Lebensprobelme’, which cannot be ‘solved’ through science, that religious belief is concerned. The problems of life cannot be stated as genuine questions since if they could, factual answers describable by science could be given: ‘If a question can be framed at all, it is also possible to answer it’ (TLP 6.5), whereas the problems of life are concerned with what cannot be said – what he refers to elsewhere as the mystical.

There are, indeed things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical. (TLP 6.522)

This approach seems to do away with the very idea of religious belief, for any belief is a claim that is either true or false. As such it must be expressible in words, placing it within the factual realm that can be understood scientifically. The religious is concerned with what cannot be put into words at all.

In his later philosophy Wittgenstein came to think that religious language is indeed possible and significant. However, what does not change is the clear distinction between how we should understand the scientific and the religious. In the early philosophy, language simply pictures the world. All beliefs are similar in that they either picture reality accurately or inaccurately, they are either true or false. It’s just that the religious falls outside this factual realm altogether. In his later period he saw language not as a mirror to reality but as something working in a wide variety of ways, not always clear from the uniform structure given by the surface grammar. ‘God exists’ and ‘Quarks exist’ look on the surface as if they are similar sentences asserting the existence of different entities. But this leads to deep confusion, for ‘the question… as to the existence of a god or God, … plays an entirely different role to the existence of any person or object I have ever heard of’ (LC p59). Language for the later philosophy becomes something completely embedded within the hurly-burly of human life rather than a set of abstract grammatical structures. Religious language works against a background of religious practices and what Wittgenstein calls, ‘forms of life’ that are quite different from those against which scientific language is used; ‘Practices give words their meaning’(RC p59). Treating religious language in the way we understand scientific language is a bit like expecting a tennis player to score a goal. Easy comparisons are absurdly misplaced.

Wittgenstein points out an obvious difference between the way we use ‘believe’ in ‘I believe in God’ to other more mundane uses. If I say ‘I believe it’s going to rain tomorrow’ I am not morally judged. ‘Normally,’ he says, ‘if I did not believe in the existence of something, no one would think there was anything wrong with this’ (LC p59). Unlike the belief that it will rain tomorrow, however, belief or unbelief in God colours how a person is viewed, and this can be positive or negative in contemporary culture.

Historical events that have a religious significance are also apt to be misunderstood if regarded in the same light as other more mundane historical events. Many Christians see Christ’s resurrection as a historical event that proves his divinity. ‘Well possibly, but possibly not’ is the response of a reasonable sceptic. Wittgenstein, however, points out that anyone who says this ‘would be on an entirely different plain’(LC p56). Such a response would be to misunderstand the practice within which the idea of the resurrection makes sense. The resurrection cannot be treated as if it is simply a documented historical event for which evidence can be gathered. It does not ‘prove’ something, in the way the battle of Hastings proved that William the Conqueror was a good military leader, for example. Both the believer and unbeliever are liable to be misled here. This point is developed further in the following:

Christianity is not based on historical truth; rather, it offers us a (historical) narrative and says: now believe! But not, believe this narrative with the belief appropriate to a historical narrative, rather: believe, through thick and thin, which you can do only as the result of a life. Here you have a narrative, don’t take the same attitude to it as you take to other historical narratives! Make a quite different place in your life for it. – There is nothing paradoxical about that! (CV p32)

He even goes as far as saying that: ‘Queer as it sounds: The historical accounts in the Gospels might, historically speaking, be demonstrably false and yet belief would lose nothing by this…’ (CV p32).

Or this:

Suppose, for instance, we knew people who foresaw the future; make forecasts for years and years ahead; and they described some sort of a Judgment Day. Queerly enough, even if there were such a thing, and even if it were more convincing than I have described, belief in this happening wouldn’t be at all a religious belief. (LC p56)

Judgement day is not something that could be predicted in this way. To think it could, would be to misunderstand how ‘judgment day’ is used within the contexts where it has its home.

Surely, the atheist might say, acknowledging the difference between religious and non-religious language does not obviate the need for evidence. Karl Popper used falsification as the criteria for meaningful explanation. If we cannot say what evidence would count as showing an explanation for empirical phenomena is false, then it must be rejected as a pseudo-explanation. Rain, for example, is caused by clouds. This is a good explanation because we know what it rules out, i.e. what would falsify it; rainfall from a cloudless sky. Similarly, the atomic physicist should be able to specify the evidence that would allow him to rule out the existence of quarks. But the belief that God exists is unfalsifiable. There are no imaginable circumstances which would allow us to conclude with certainty that God does not exist. Horrific events in a believer’s life might shake their faith but such events are completely consistent with the existence of God. Various theodicies have been produced by theologians since medieval times to overcome the ‘problem of evil’. The Lisbon earthquake of 1755 in which approximately 30,000 people died shook the faith of many in the Catholic church and had a considerable effect on the development of enlightenment thinking. It did not disprove God’s existence. But failing the falsification test is not a reason to claim the idea of God is somehow illegitimate. All it means is that God is not a scientific concept so evidence (in the scientific sense at least) is irrelevant. There is a distinctly religious way of talking about the world which is not concerned with causal mechanisms as science is. In a revealing and enigmatic comment Wittgenstein says:

When someone who believes in God looks around him and asks ‘where did everything that I see come from?’ ‘Where did everything come from?’, he is not asking for a (causal) explanation; and the point of his question is that it is the expression of such a request. Thus, he is expressing an attitude towards all explanations. – But how is this shown in his life? It is the attitude that takes a particular matter seriously, but then at a particular point doesn’t take it seriously after all, and declares that something else is even more serious. (RC p58)

In the Tractatus there is a sense that scientific (i.e. causal) explanations are not enough, for after ‘all possible scientific questions have been answered’ problems remain. Language, however, plays a role in the later philosophy. We don’t want another theory to compete with science, but there’s a place for an overall perspective on all explanations – not a cause, but a reason to make sense of all explanations, something that is ‘even more serious’. Atheists express this same idea but in terms of an absence. I have heard a friend say ‘the universe doesn’t care about us’, which strikes me as a surprisingly religious thing to say. The word ‘care’ makes sense in this context. An absence of care is not the same as the inapplicability of the very idea of care. And many non-believers still find it meaningful to rage against a God they don’t believe in.

In contemporary culture the model of scientific truth is so dominant it’s difficult for even fully committed theists to avoid becoming influenced by it. The existence of God is so easily regarded as a contingency, just like the existence of a scientific entity. One of Wittgenstein’s most direct comments on the nature of a belief in God comes in the following:

Life can educate one to a belief in God. And experiences are what bring this about; but I don’t mean visions and other forms of sense experience which show us the ‘existence of this being’, but, e.g. sufferings of various sorts. These neither show us God in the way a sense impression shows us an object, nor do they give rise to conjectures about him. Experiences, thoughts – life can force this concept on us. So perhaps it is similar to the concepts of an object. (CV p86)

Facts about the human condition – that we are capable of suffering, of living unfulfilled lives, of being vulnerable and so on – allow us to make sense of a belief in God. One can perhaps imagine a kind of being for which such a belief would make no sense at all; it might in fact be argued that the project of transhumanism, where technology is developed to such an extent that all these ‘weaknesses’ are overcome, is aiming for just such a being. But apart from the obvious vulnerabilities of our biological nature there are deeper existential problems embedded within the human condition. Perhaps these are what Wittgenstein has in mind when he talks of ‘the problems of life’. William James talks of an ‘uneasiness’ which he claims is directly linked to a religious response to the world, and which ‘reduced to its simplest terms, is a sense that there is something wrong about us as we naturally stand.’[3] A similar idea is central to the existential philosophers from Kierkegaard onwards. The human condition and belief in God cannot be separated.

But what is meant by the last line; ‘So perhaps it is similar to the concepts of an object.’? I think it pinpoints the idea that God cannot be understood as just another existing entity, however all powerful; something believers include in their list of things which exist and atheists leave out. It also indicates the inappropriateness of the notion of ‘evidence’. We have evidence for the existence of this particular tree or that particular building, but we do not have evidence for objects in general in anything like the same way. Of course we can claim there is overwhelming evidence for the existence of objects, just as the mediaeval peasant might see God in everything he encounters. But it’s also possible to understand experience without reference to objects, or indeed to God. Whether this is a sustainable perspective for human beings is, I suppose, an open question.

Abbreviations – works by Wittgenstein or Lectures Notes and Conversations:

RW – Recollections of Wittgenstein, ed. Rush Rhees, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1984

TLP – Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, trans D.F Pears and B.F. McGuiness, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1961

LC – Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief., ed. C. Barrett, Blackwell, Oxford, 1966

RC – Remarks on Colour, ed. G.E.M. Anscombe, trans. L.L. McAlister and M. Schattle, Blackwell, Oxford, 1077.

CV – Culture and Value, ed. G.H. von Wright in collaboration with Heikki Nyman, trans. Peter Winch, Blackwell, Oxford, 1980.

[1] I have drawn extensively on Fergus Kerr’s work Theology after Wittgenstein, 1986, Blackwell, Oxford.

[2] p32, Theology after Wittgenstein.

[3] James, W. 1985, Varieties of Religious Experience, Penguin Classics, London (originally published 1902) p508