by Marie Snyder

I dipped my toe into Stoic Week again this year. I’ve done it before a decade ago, and even went to StoicCon once! I was hoping to find the attitude necessary to manage all this (gestures broadly at everything). I got stuck on the first day.

I dipped my toe into Stoic Week again this year. I’ve done it before a decade ago, and even went to StoicCon once! I was hoping to find the attitude necessary to manage all this (gestures broadly at everything). I got stuck on the first day.

They start with Epictetus’s bit on figuring out what we can control and what we can’t:

Some things are under our control, while others are not under our control. Under our control are conception [the way we define things], intention [the voluntary impulse to act], desire [to get something], aversion [the desire to avoid something], and, in a word, everything that is our own doing; not under our control are our body, our property, reputation, position [or status] in society, and, in a word, everything that is not our own doing.

It’s from the Encheiridion, or handbook, which is a short read and pretty accessible.

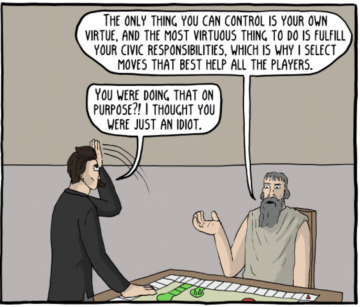

I get the gist of it. A lot of the time when we’re bothered by something, we can’t control what’s going on in the world, but we can control our attitude towards it. It’s only bad because we think it’s bad. The thing to do in all cases is to act virtuously because that’s all that’s within our control. Comedian Michael Connell explains the stoic attitude in an analogy about late trains. If we’re in a hurry, news of a late train is a tragedy. But if we’re stuck on the tracks, it’s fantastic! But in the face of Covid, climate change, and the many conflicts around the world, how do we shift this news to be anything but horrific? The only perception that can spin it as good seems to be genocidal in nature.

So maybe I’m overthinking it, but I have questions about what Epictetus specifically says here.

First of all, how is desire under our control? I can’t control what desire to have or not have, but I can notice it and decide what to do with it if I have my wits about me. If I’m tired, then sometimes even my behaviour feels not remotely within my control. With practice, I think we can reduce the intensity of some desires or desensitize ourselves from aversions, but desire is pretty automatic. We desire or are repelled in an instant. Epictetus is calling on us to do that practice every day, but it only gets us so far. Even just being able to take a beat to consider the situation is a challenge when we’re overwhelmed with demands on it.

Something else I’ve struggled with when I read this bit is how do we know with any certainty what we can control. For instance, do we have any control over climate change? I can sort my recycling perfectly, and it could still all end up in the dump. I can avoid the use of fossil fuels for everything and not eat meat and write tons of emails to all elected officials, but I’ll never be able to do enough to make a difference. My influence is sorely limited, but is it entirely limited?

If you try to change things that are outside of our control “you will be hampered, will grieve, will be in turmoil, and will blame both gods and men”! If we just worry about being a good person, then we’re untouchable. We won’t be upset by things outside of ourselves. I can get on board when it comes to managing disappointment when I break a favourite cup, but should our goal be to watch the world burn with disinterest?

I don’t have the power to make a significant effect on my own, so is that to suggest that I have no control over the situation and should stop trying to make a dent in things beyond my own efforts? Because what if I can end up influencing others to change their actions. It’s not within my control, but it might have an effect. It might be within my influence. If we only act on what we can control, then nobody would do anything to try to change other people’s behaviours, and that’s just not how society works! From social graces to legislation, we have to affect one another’s behaviours to some extent in order to live together. We take it for granted that it’s necessary to have some agreed upon rules with consequences.

Our attitude to it all can be the difference between constant frustration and calm. Keep fighting to change the world in order to reduce the effects of climate change as much as possible while detaching from any potential outcome. That feels more Buddhist than Stoic, though.

Epictetus has this other bit that I do really like: Whenever you’re about to deal with other people, take a minute to remind yourself how much it can suck and prepare for that:

“If you are going out of the house to bathe, put before your mind what happens at a public bath–those who splash you with water, those who jostle against you, those who vilify you and rob you. And thus you will set about your undertaking more securely if at the outset you say to yourself, ‘I want to take a bath, and, at the same time, to keep my moral purpose in harmony with nature.’ And so do in every undertaking. . . . Keep before your eyes day by day death and exile, and everything that seems terrible, but most of all death; and then you will never have any abject thought, nor will you yearn for anything beyond measure.”

Then if you want a nice time and to be moral, if people are jerks to you, at least you can still be moral and get half of what you had hoped for! Temper expectations in order to avoid disappointment. Remember that we’re all here for a very short time, and don’t sweat the small stuff.

Part of my problem — why I suffer internal tumults — is that I keep hoping people will care more about the world than minor personal conveniences. I think they’ll stop driving to the corner store or start using a travel mug for their numerous coffee trips or stop travelling by plane for every vacation or reduce how much meat they eat. I’m repeatedly disappointed that most people aren’t getting on the right road to long-term survival. Epictetus implies that I’ll be significantly better off if I just expect less of people.

But that seems so much worse. If I believe people won’t change, and my emails to all the leaders are useless, and there’s really no hope, then not experiencing despair feels disconnected. It feels heartless. But then again, my despair isn’t helping anyone anywhere, so if I practiced enough, could I be happy while watching more videos of massive floods and fires??

I think it might be less painful to be deluded by a bit of false optimism that allows me to believe that one day someone might hear me out and bike to work instead of driving, then enjoy it so much they start cycling everything, than to be realistic and accept that too few of us will get our collective shit together soon enough to turn this mess around.

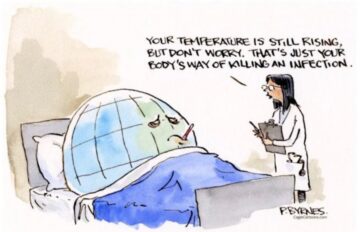

Epictetus’s suggestion to “wish for everything to happen as it actually does happen, and your life will be serene” feels barbaric in these times. That would mean wishing for the destruction of nature, since we’re not meeting biodiversity targets, and barely trying because it’s too expensive. “Dr. Jane Goodall said our future is ‘ultimately doomed’ if we don’t address biodiversity loss.” It’s clear that wishing for things to be as they are can take away the annoyance when someone eats the last cupcake, but it’s impossible to do with so much knowledge of the world. What kind of monster can wish for child prostitution, slavery, torturous dictators, enormous floods, starvation, and unfettered greed ever increasing these problems? It’s likely far easier to follow these precepts when unaware of what’s going on elsewhere and what’s coming down the pipe.

If my goal in every task is to do the task and to “keep my moral purpose in harmony with nature,” then I’m to take some comfort in the fact that, even if I don’t meet my task-goal, and even if I get robbed and beaten trying — more likely just humiliated — then at least I was still able to do that moral purpose thing. But I still have a really hard time caring about being unaffected by the situation when so many in power are so out of tune with nature that it’s collapsing.

Don’t “hand over your mind to any person that comes along, so that, if he reviles you, it is disturbed and troubled” is great advice, though. Haters gonna hate. People who care about things, about the climate or covid or conflict, are often the butt of jokes. About a decade ago at my old school, as I was trying to get people to use less paper or turn off lights and electronics — trying to change a mindset of wastefulness into an awareness of our effect on the world — I was met with jeers and photoshopped images suggesting I expect our school to be underwater one day (I mean from the staff – the kids were great), and that image comes back whenever I see the floods elsewhere. People laugh until it hits their front door.

And then they get mad that nobody told them.

We need leaders who will act on this, but many are not up to the job. Epictetus admonishes,

“If you undertake a role which is beyond your powers, you both disgrace yourself in that one, and at the same time neglect the role which you might have filled with success.”

But climate change isn’t just on leaders. We all have to change how we live. We will change how we live either by design or misfortune. The oceans are becoming too acidic to sustain life and trees are no longer absorbing CO2 like they used to. Last year, “historical temperature and ice extent records were broken by enormous margins.” A few years ago, our hope was to keep global temperatures below 1.5°C above baseline, but we’ve blown past that at 1.65 right now, and our current policies are leading us towards 3.1°C within 75 years, which isn’t something we can survive.

Climate scientist Kevin Anderson warns that over half the emissions come from 10% of the population, mainly from the wealthier parts of the world, so equity between nations is key. But within each nature is an inequity as well. There, too, emissions are driven by the wealthy 10%, the profs, journalists, teachers, doctors, and they’re also most insulated from the early impacts of climate change. If you’re reading this, you’re likely part of this group. WE are the problem that needs to be addressed. Anderson says,

“That particular group, the last thing they want is to make changes in their lifestyles. They won’t do it voluntarily. We need legislation to drive social change. … We’ve left it so late, any response will be revolutionary. At this point, there is no non-radical way out of this. … Organized, structured, change with less suffering is preferable.”

The wealthy won’t act without legislation, but we can’t have legislation on this because the wealthy people won’t like it. It’s a circular clusterfuck. It feels like nothing good can come from it, but maybe that’s just an attachment I have to the human species that I need to let go of!

In Canada, Alberta premier Danielle Smith recently announced that we’re going to “unapologetically double our oil and gas production.”

Epictetus says,

“Signs of one who is making progress are: He censures no one, praises no one, blames no one, finds fault with no one.”

Um, no.

I take some solace that Epictetus also tells us to take pains to make sure women over 14 know they’re only valued for their modesty, and that we should avoid making people laugh because it might lead to a vulgarity. He says that like vulgarity is a bad thing!

Like with all of philosophy (and psychology and religion), we can take the parts that work for us, and leave the sections that no longer make sense or don’t result in a decrease in overall suffering. It helps to have clear and firm values to follow, but where would we be if we didn’t try to influence others to have them too?

As this recent article in BioScience a lengthy list of authors say,

“It is our moral duty and that of our institutions to alert humanity to the growing threats that we face as clearly as possible and to show leadership in addressing them.”

Absolutely.