A couple of weeks ago The New York Times ran an op-ed in which Drew Lictenberg, who is the artistic producer at Shakespeare Theatre Company, pointed out that there has been a drop in Shakespeare productions recently:

American Theatre magazine, which collects data from more than 500 theaters, publishes a list of the most performed plays each season. In 2023-24, there were 40 productions of Shakespeare’s plays. There were 52 in 2022-23 and 96 in 2018-19. Over the past five years, Shakespeare’s presence on American stages has fallen a staggering 58 percent. At many formerly Shakespeare-only theaters, the production of the Bard’s plays has dropped to as low as less than 20 percent of the repertory.

Why might American theaters be running away from Shakespeare?

After pointing out that Shakespeare productions can be costly, a problem exacerbated by Covid-19, Lictenberg points to political and cultural polarization:

Given contemporary political divisions, when issues such as a woman’s right to control her own body, the legacy of colonialism and anti-Black racism dominate headlines, theater producers may well be repeating historical patterns. There have been notably few productions in recent years of plays such as “The Taming of the Shrew,” “The Tempest” or “Othello.” They may well hit too close to home.

Why be concerned about this drop? Things change. If and when the polarization lessens, Shakespeare will come back. Won’t he? What if the polarization persists? Is it possible that Shakespeare will never come back? What would that mean?

I warn you, however, that I do not intend to answer those questions. I don’t see how that’s possible. Rather, I present them as a way to begin thinking about the position that Shakespeare occupies in the imagination of well, you know, us, a bunch of people oriented toward Western culture.

The Centrality of Shakespeare

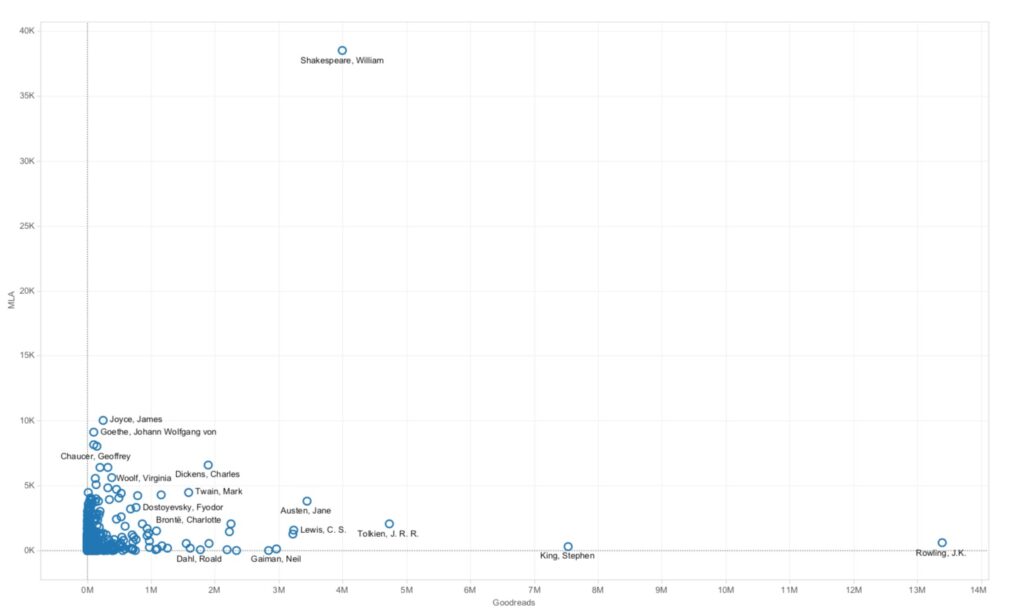

Back in 2018 J. D. Porter was interested in how the content and structure of the (Western) literary canon was affected by elite prestige and mass popularity. To examine this he began with a list of 1,406 authors collected from various sources. He then counted how many times each author was listed in two sources. He estimated the prestige each author by how many times their books were mentioned in articles collected in the MLA International Bibliography, which lists academic articles. To estimate mass appeal Porter counted up their appearance on Goodreads, a website where people can rate and review books. At the time of the study the site claimed 50 million users and a database of over a billion books.

Consider the graph below. The elite count is presented along the Y axis (left) while the popularity count is arranged along the X axis (bottom).

Notice that most of the authors are bunched up at the lower left-hand corner. Shakespeare ranks considerably lower in popular appeal than Rowling or King, who are near the bottom in elite appeal. He’s fourth behind Tolkien. When we move to the top of the chart we see that he ranks considerably higher in elite appeal (academic interest) than any other author. Joyce, Goethe, Chaucer, or Woolf rank highest below Shakespeare. They are gathered to the left, indicating that, whatever their literary prestige, they aren’t terribly popular.

Shakespeare’s position in the literary universe is unique. No other author is close to him. I take that as a crude indicator of Shakespeare’s centrality.

Now, consider the fact that along the popularity axis (bottom), while Shakespeare is outranked by three authors – two by a considerable margin, there are others close behind him (Jane Austen, C. S. Lewis, Neil Gaiman). But no one is even close to him on the prestige axis (left). Why is Shakespeare mentioned so much more in academic articles than any other author?

I’ll give you a clue from my own history. My PhD is in English literature. I was mostly interested in methodological and theoretical issues, but I did take two courses on Shakespeare, one on the comedies and the other on the tragedies. I did that, not because I had a special attraction for Shakespeare, though I like him well enough, but because I figured that I would want to use his work as examples in my methodological and theoretical work. Why? Because I figured that more literary scholars would have read Shakespeare than any other single author, this giving my methodological work maximum appeal. Shakespeare’s a useful point of reference.

Reference points are important for the coherence of a community, in this case a community of scholars – which, by the way, is considerably smaller than the 50 million users of Goodreads. Ten reference points, say, spreads the community’s attention too widely. One reference point gives it a sharp focus. [1]

Shakespeare is Strange

A couple of years ago Maya Phillips wrote a critique of color-blind casting for The New York Times. Phillips asserts:

Any casting of a performer in the role of a race other than their own assumes that the artist step into the lived experience of a person whose culture isn’t theirs, and so every choice made in that performance will inevitably be an approximation. It is an act of minstrelsy.

For the sake of argument, let us accept that at face value. As one example Phillips indicates the Japanese landlord Mickey Rooney played in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, a thoroughly cringe-worthy example. She used Laurence Olivier in Othello as another example.

It’s not clear what the notions of either “lived experience” or “culture” will get us in that case. Othello is an early 17th century play based on a mid-16th story by Cinthio, an Italian writer. Whose lived experience is supposed to provide the touchstone of authenticity, Shakespeare’s or Cinthio’s? Shakespeare was white. Should he thus not have written the role of Othello? Were there any black actors available to play the role? Not likely. Then we have Desdemona. For maximum authenticity Olivier should have acted to a Desdemona played by an adolescent boy. For that’s how the role would have been played in Shakespeare’s time; women didn’t act in the Elizabethan theatre.

I can only assume that Phillips, and her editors, have become so comfortable with Shakespeare that the distance of Shakespeare’s world from our own slipped their minds. By any reasonable definition of “culture” any contemporary actor playing any role in Shakespeare has no choice but to “step into the lived experience of a person whose culture isn’t theirs.” The culture of Elizabethan England is dead, to everyone, including to Londoners. The language, while recognizable as English, is nonetheless foreign. Contemporary speakers of English, any kind of English, cannot speak it fluently and, if transported back to Shakespeare’s London in a time machine, they would have trouble making themselves understood and would, in turn, have trouble understanding others. The pronunciation is strange and many words are foreign.

So, you are reading along in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and encounter, “The starry welkin cover thou anon /With drooping fog as black as Acheron.” “Welkin”? What’s that? It’s the sky. A footnote will tell you that, though you’ve got to interrupt your forward motion to check down at the bottom of the page.

But you don’t even have that if you’re attending a live performance. What about “cacodemon,” “dandiprat,” “pash,” “sneap,” “coistrel,” “elf-skinned,” or “smicket”?[1]

Some years ago the linguist, and avid theatre-goer, John McWhorter observed:

The tragedy of this is that the foremost writer in the English language, the most precious legacy of the English-speaking world, is little more than a symbol in our actual thinking lives, for the simple reason that we cannot understand what the man is saying. Shakespeare is not a drag because we are lazy, because we are poorly educated, or because he wrote in poetic language. Shakespeare is a drag because he wrote in a language which, as a natural consequence of the mighty eternal process of language change, 500 years later we effectively no longer speak.

Is there anything we might do about this? I submit that here as we enter the Shakespearean canon’s sixth century in existence, Shakespeare begin to be performed in translations into modern English readily comprehensible to the modern spectator. […] The translations ought to be richly considered, executed by artists of the highest caliber well-steeped in the language of Shakespeare’s era, thus equipped to channel the Bard to the modern listener with the passion, respect and care which is his due.

This kicked up a bit of a fuss, as you can see, for example, in this debate with David Crystal.

While I’m sympathetic to McWhorter’s proposal, my point here is simply that Shakespeare’s language is strange. Will the time come when English has changed so much that Shakespeare will seem as foreign as Chaucer now does? I can’t help but think that even as we think of Shakespeare as being ours, we value him for the veneer of exoticism his language betokens. And that exoticism makes is that much easier to regard him, in McWhorter’s words, as “little more than a symbol in our actual thinking lives.”

Would Shakespeare Vote for Donald Trump?

Let us return to the present, but not to the drop in Shakespeare performances, though we’ll return there in a minute. I want to look at the current presidential election, Trump vs. Harris. What would Shakespeare think? How would he vote?

These are perhaps absurd, unanswerable questions. Humor me. Think of them as a device for mapping out a space, the space of Shakespeare in our culture.

Imagine that we’ve gone back in time, dragooned him into our time machine, and brought him forward into the present. Just as his world would seem strange to us, so would our world seem strange to him, including the language. He lived in a monarchy, not a democracy. The politics he depicted in his history plays was about aristocratic maneuvering, not the issues animating the current election, such as immigration, jobs, abortion, racism, or even religion. Not that religion was unimportant in Elizabethan England. It was very important, but it was a different kind of issue. The relationship between Protestantism and Catholicism was the primary religious question and church and state were not separate. Elizabeth headed both.

How could he make sense of voting if he were just plopped into the middle of it all? I assume he’d have little trouble understanding the idea of voting, but actually doing it, that’s something else. Without actually living in the country for several years, at least, how could Shakespeare have any idea what’s a stake? So perhaps he should live here for a while – how would he earn a living? – and go through the process of becoming a citizen.

Let’s set all that aside and ask a fairly specific question: What would he think of Donald Trump? I have in mind a specific scene in Henry IV, Part 2, known as the rejection of Falstaff. As you may recall, Sir John Falstaff is a down-and-out knight who spends his time drinking with his pals and trading in petty crime. Prince Hal, heir apparent to the throne of England, is one of those pals. When Hal ascends to the throne, becoming Henry V, Falstaff approaches him at the coronation, gleefully anticipating good times to come now that his boon companion, good old Hal, rules the land. He addresses the King as “Hal” and is severely, unexpectedly, and very publicly reprimanded (Henry V, Part II, Act 5, scene 5):

I know thee not, old man: fall to thy prayers;

How ill white hairs become a fool and jester!

I have long dream’d of such a kind of man,

So surfeit-swell’d, so old and so profane;

But, being awaked, I do despise my dream. […]

Reply not to me with a fool-born jest:

Presume not that I am the thing I was;

For God doth know, so shall the world perceive,

That I have turn’d away my former self;

So will I those that kept me company.

Notice how Hal explicitly distinguishes his two selves, the private person (“the thing I was”, “my former self”) and his new status as king. As a consequence of this distinction the King must necessarily have a different relationship with Sir John than Hal did.

Hal, become Henry V, is drawing a distinction between his personal life and his public life, as monarch. He is telling Falstaff that he will not transfer or transmute his personal relationship with Falstaff into a public relationship based on his new status as king. He is differentiating between personal life and public life.

And that is something Donald Trump has difficulty doing. It’s clear that he values personal loyalty above all else and that he will do everything he can to treat the presidency as his personal fiefdom, as he did in his previous term. Would Shakespeare reject Trump as Henry V rejected Falstaff?

A question: If prospective Trump voters were to watch a performance of Henry IV, Part 2, how likely would that change their minds against Trump?

Beyond Shakespeare?

What then are we to make of the point where we began, with a recent drop in Shakespeare performances at professional companies? Lictenberg suggest that the drop reflects current polarization along cultural and political lines. That seems plausible to me. I have no idea whether or not or when that polarization will dissipate, much less how that will affect Shakespeare performance.

But there is another issue, Shakespeare’s age. His texts are old enough and the language just strange enough that that causes problems. And his world, customs and mores, social, economic, and political institutions, technology, and communication media, all that is quite different from our world. Moreover, recent developments in AI put our world on the edge of fundamental change which we cannot predict. What does Shakespeare have to tell us about these strange creatures we are creating?

If Shakespeare can’t hold the center, who will? Such very different thinkers as Harold Bloom and J. Hillis Miller have pointed out that we are moving beyond the print age. Will new reference points in new media emerge into the center? Will there even be a center?

One might, of course, point out that there are texts even older than Shakespeare, much older, that remain culturally central. I’m thinking of ancient religious texts such as the Torah, the Christian Bible, the Vedas, the Buddhist Sutras, and so forth. But those text maintain their centrality through the institutions which have been built around them.

* * * * *

[1] For further discussion of Shakespeare’s position in the canon see a couple of my posts at New Savanna: What does evolution have to teach us about Shakespeare’s reputation? June 4, 2024, and I was right, Shakespeare isn’t real (Lit Lab 17), March 30, 2024.

[2] ChatGPT coughed up those words for me, and others as well. Here’s what they mean:

cacodemon – an evil spirit or demon

dandiprat – a term for a small or insignificant person

pash – to smash or crush something

sneap – to rebuke or scold

coistrel – a low, worthless fellow or knave

elf-skinned – thin-skinned or small in stature, used as an insult

smicket – a smock or undergarment for women

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by William Benzon

by William Benzon