by Marie Snyder

I dipped my toe into Stoic Week again this year. I’ve done it before a decade ago, and even went to StoicCon once! I was hoping to find the attitude necessary to manage all this (gestures broadly at everything). I got stuck on the first day.

I dipped my toe into Stoic Week again this year. I’ve done it before a decade ago, and even went to StoicCon once! I was hoping to find the attitude necessary to manage all this (gestures broadly at everything). I got stuck on the first day.

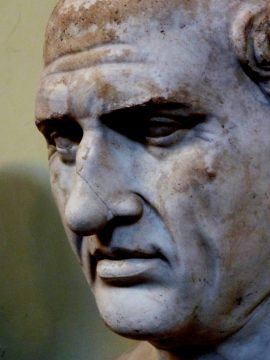

They start with Epictetus’s bit on figuring out what we can control and what we can’t:

Some things are under our control, while others are not under our control. Under our control are conception [the way we define things], intention [the voluntary impulse to act], desire [to get something], aversion [the desire to avoid something], and, in a word, everything that is our own doing; not under our control are our body, our property, reputation, position [or status] in society, and, in a word, everything that is not our own doing.

It’s from the Encheiridion, or handbook, which is a short read and pretty accessible.

I get the gist of it. A lot of the time when we’re bothered by something, we can’t control what’s going on in the world, but we can control our attitude towards it. It’s only bad because we think it’s bad. The thing to do in all cases is to act virtuously because that’s all that’s within our control. Comedian Michael Connell explains the stoic attitude in an analogy about late trains. If we’re in a hurry, news of a late train is a tragedy. But if we’re stuck on the tracks, it’s fantastic! But in the face of Covid, climate change, and the many conflicts around the world, how do we shift this news to be anything but horrific? The only perception that can spin it as good seems to be genocidal in nature.

So maybe I’m overthinking it, but I have questions about what Epictetus specifically says here.

First of all, how is desire under our control? I can’t control what desire to have or not have, but I can notice it and decide what to do with it if I have my wits about me. If I’m tired, then sometimes even my behaviour feels not remotely within my control. With practice, I think we can reduce the intensity of some desires or desensitize ourselves from aversions, but desire is pretty automatic. We desire or are repelled in an instant. Epictetus is calling on us to do that practice every day, but it only gets us so far. Even just being able to take a beat to consider the situation is a challenge when we’re overwhelmed with demands on it. Read more »

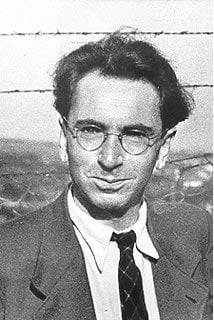

The second half of Frankl’s

The second half of Frankl’s