by Sherman J. Clark

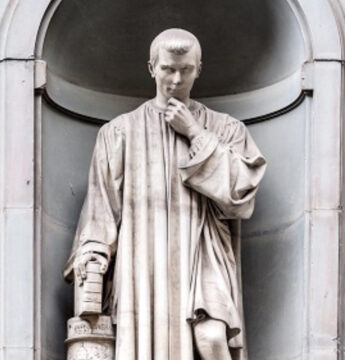

There is no other way of guarding oneself from flatterers except letting men understand that to tell you the truth does not offend you. —Machiavelli

A friend recently described to me his research in quantum physics. Later, curious to understand better, I asked ChatGPT to explain the concepts. Within minutes, I was feeling remarkably insightful—my follow-up questions seemed penetrating, my grasp of the implications sophisticated. The AI elaborated on my observations with such eloquence that I briefly experienced what I can only describe as Stephen Hawking-adjacent feelings. I am no Stephen Hawking, that’s for sure. But ChatGPT made me feel like it—or at least it seemed to try. Nor am I unique in this experience. The New York Times recently described a man who spent weeks convinced by ChatGPT that he had made a profound mathematical breakthrough. He had not.

To be clear: Chat GPT was very helpful to me as I tried to understand my friend’s work. It explained field equations, wave functions, and measurement problems with admirable clarity. The information was accurate, the explanations illuminating. I am not talking here about AI fabrication or unreliability. And in any event, it does not matter whether a law professor understands quantum physics. The danger wasn’t in what I learned or failed to learn about physics—it was in what I was l was at risk of doing to myself.

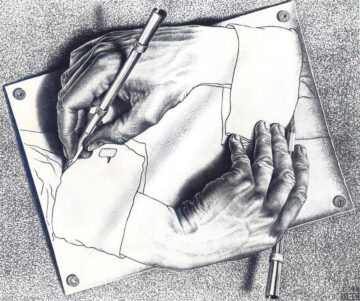

Each eloquent elaboration of my amateur observations was training me in the wrong intellectual habits: to confuse fluent discussion with deep understanding, to mistake ChatGPT’s eloquent reframing of my thoughts for genuine insight, to experience satisfaction where I should have felt appropriate humility about the limits of my comprehension. I was nurturing hubris precisely where I needed to develop humility. And, crucially, intellectual sophistication does not guarantee immunity. Anyone who has spent time on a college campus knows that intellectual hubris has always flourished among the highly educated. It is hardly a new phenomenon that cleverness and sophistication can be put to work in service of ego and self-deception.

What makes AI different is that it has become our companion in this self-deception. We are forming relationships with these systems—not metaphorically, but in the practical sense that matters. Read more »

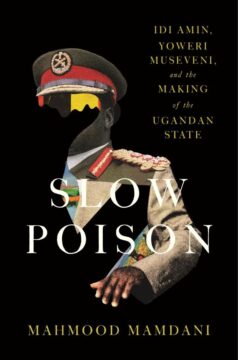

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

When I turned fifty, I went through the usual crisis of facing that my life was—so to speak—more than half drunk. After moping a while, one of the more productive things I started to do was to write letters to people living and dead, people known to me and unknown, sometimes people who simply caught my eye on the street, sometimes even animals or plants. Except in rare cases, I haven’t sent the letters or shown them to anyone.

When I turned fifty, I went through the usual crisis of facing that my life was—so to speak—more than half drunk. After moping a while, one of the more productive things I started to do was to write letters to people living and dead, people known to me and unknown, sometimes people who simply caught my eye on the street, sometimes even animals or plants. Except in rare cases, I haven’t sent the letters or shown them to anyone.

Sughra Raza. First Snow. Dec 14, 2025.

Sughra Raza. First Snow. Dec 14, 2025. One Monday in 1883 Southeast Asia woke to “the firing of heavy guns” heard from Batavia to Alice Springs to Singapore, and maybe as far as Mauritius, near Africa.

One Monday in 1883 Southeast Asia woke to “the firing of heavy guns” heard from Batavia to Alice Springs to Singapore, and maybe as far as Mauritius, near Africa.