by Jeroen Bouterse

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

Neurath was a capable scholar with good ideas, a newspaper recorded Weber as saying; but recently he seemed to have somewhat lost his grip on reality.[1] That judgment would refer to Neurath’s economic thinking. In particular, his belief that a planned economy was viable, to an extent that the entire money economy could be abolished. This conviction, the seeds of which were planted by the economic thought of his father, and which was strengthened by his study and experience of war economies during the 1910s, would in fact be lifelong; Neurath would always be thinking of concrete ways to make co-operation and planning a reality.

His position as head of the ‘Central Economic Administration’ of Bavaria (to which, importantly, he had been installed before the communist coup) had given him an opportunity to realize his ambitious and radical ideas for economic “socialization”. In spite of warnings from his friends and his wife, he showed no inclination to let that slip just because he was now working for Bolsheviks. After the case, Weber would tell Neurath in a private letter that for all his good intentions he had lent his service to tyrants, and that his utterly frivolous and irresponsible plans risked discrediting socialism for a century.[2]

Neurath is now most famous not for this radical experiment, but for his role in the Vienna Circle and the unity of science movement. He also shares with Theseus the honor of having a philosophical parable named after him involving the piecemeal reconstruction of a boat. I myself started reading about him because of my hobby horse: perspectives on the distinction between sciences and humanities. This essay will in the end try to fit in his ideas on that with the rest of his thought, but all the other stuff is so interesting that it is hard to focus. Perhaps it is fitting in that regard to recount what historian of antiquity Eduard Meyer said about Neurath’s dissertation on ancient economic thought: very good yes, but rendered less appealing “by unnecessary deviations from the substance matter, by an inability to suppress any little idea”.[3] It happens to the best of us. But back to the main topic.

Unity of mankind

Although, why not start with Meyer. In the introduction of his study of the ancient world, the famous historian had decided to take a stance in a methodological debate on the status of laws in history. Basically, Meyer believed the search for laws did not concern the historian: although he could of course use insights from other disciplines, the historian’s occupation was with the one-off-ness of the past. “The unique, the singular, that never repeats itself, but is always shaped differently, this is the field of historical science. For that reason, it does not belong to the philosophical and natural-scientific disciplines, and any attempt, to measure it to their standards, is improper, and distorts its nature.”[4]

Other perspectives were available. Max Weber had dissected an earlier iteration of Meyer’s views and proposed in its place a view in which the study of human societies was much more integrated in a search for patterns. Ever courteous, Weber emphasized that Meyer was a pre-eminent historian who could obviously be relied on to understand his own field and who “indeed, has come quite close on several occasions to a logically appropriate phrasing of what is correct in his account.”[5] For Meyer and Weber, as for many other scholars in the decades around 1900, the relation between the natural sciences and the study of the human world, between the general and the unique, lawfulness and freedom, objectivity and values, the natural and the human, were all up for debate, in a Methodenstreit which simultaneously negotiated the differences between the sciences and the humanities and carved out something of a niche for the social sciences.

As a student in Berlin, Neurath was aware of these discussions. Rather than parroting one of the existing options, he would stake out his own position, informed by his own ideas on social science. In particular, his far-reaching, borderline utopian optimism about its potential is key to understanding both his views on the sciences and humanities and his tireless, lifelong drive to find scientifically informed ways to further the conditions for human well-being.

Effective social policy had to take everything into account, and taking everything into account meant ignoring any supposedly impenetrable conceptual borders. As Nancy Cartwright and Jordi Cat have emphasized, Neurath’s taste for unity in science was rooted in his pragmatic goals – “common action presses us towards a unified science”, they quote.[6] Science properly understood would not contain divisions; the suggestion of incommensurability between disciplines (the term is a bit of an anachronism, but we saw the idea explicitly voiced by Meyer just now) must come from outside of science – is metaphysics – and needs to be expelled from it. “Scientific terms bring together, metaphysical terms divide”, as Neurath would come to summarize later.[7]

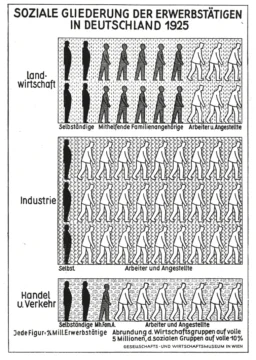

The statement echoed a slogan he used in the 1920s during his work in Vienna. After being involved for several years in a movement for communal housing, Neurath shifted his efforts to leading a museum for society and economy, for which he and his colleagues developed a highly recognizable and influential form of visual statistical representation: the ‘Vienna Method’, later called Isotype. The illustrations below come from a recent history of Isotype, by Christopher Burke and by Neurath’s biographer Günther Sandner. This plate shows the social distinctions in different sectors of the economy in 1925 Germany.

The abstract, hieroglyph-like pictures, associated primarily with his collaborators Gerd Arntz and Marie Reidemeister (whom Neurath would marry after the death of his second wife), were explicitly meant to include as many people as possible in the understanding of social science. They should remove barriers of (formal) education and language as much as possible. Indeed, if you don’t read any German, I’m sure you will still be able to gather a lot from this chart, and that was precisely Neurath’s intention. “Words divide, pictures unite”, he liked to say.

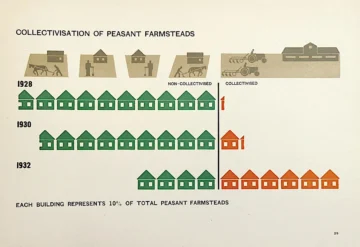

Neurath still used that slogan when writing for a Moscow newspaper in 1932, about the adoption of the Vienna method by the Soviet-Union.[8] He was actively involved in this cooperation, dispatching staff from the Vienna museum to the ‘Izostat’ institute for pictorial statistics to advise the Soviets. In lending his expertise, Neurath undoubtedly intended to enhance popular understanding of social statistics; however, in helping to visualize data provided directly by the government (such as projected results of Five-Year Plans), he also risked boosting the credibility of the domestic and international propaganda of a bloody autocracy. Burke and Sandner show that Izostat produced charts celebrating collectivization even as millions of people were dying of the famine in Soviet Ukraine:[9]

In Vienna, pictorial statistics continued after Neurath left Austria because of the fascist takeover in 1934; pictograms were now dedicated to furthering “patriotism”.[10] After the Anschluss in 1938, the Austrian Institute for Pictorial Statistics employed a variant of the Vienna Method to stoke antisemitic hatred, for example through a chart purporting to show the ‘Judaization’ of different professions.[11] Reminders that, unfortunately, new forms of expression and new media can always be put to less enlightened use. If there is truth in Neurath’s slogans, it is not as a literal thesis about what kinds of expressions can in fact be used to divide people; it is that lots of supposed differences are fictions that can be overcome. Overcome, in particular, by presenting facts in a way that stays closer to the things.

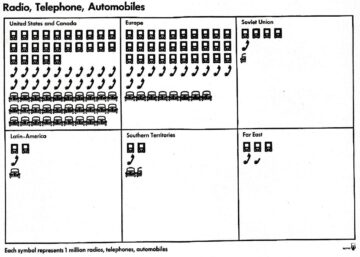

One monument to the progressive use to which Neurath himself sought to use the Isotype presentation technology is the English-language publication Modern man in the making, prepared in 1939.[12] It is still a visually impressive book, presenting a view on the modern world through a range of statistical charts and maps on historical and social topics such as mortality, mechanization, unemployment, and migration. The images command most of the reader’s attention; but in the meantime, Neurath’s simple prose provides a narrative of the historical tendencies of modernity in terms of the “unification of mankind”. How war and peace turned global, for instance, is shown by comparing the relatively tiny region that was involved in the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia to the treaties after the (first) World War. (31).

Neurath discusses the contingency of military alliances and of war itself – there is neither an inevitable tendency to violence, nor an ‘instinct’ against it; it all comes down to the structure of social life. The case for economic planning is made, again on the grounds that it is already common in war economies. Co-operation is deeply modern, if modernity is defined roughly as denoting social trends that tend to spread over the globe. (No society would choose to adopt the crises and insecurities of the “profit system”, proving that system to be unmodern.) Co-operation is also furthered by the spread of modern communication and transportation technology, which, when not restricted by censorship, will “perform their proper function of making nations better acquainted with each other” (108, illustration from the same page).

Scientists know how to change the surface of the earth; now it is time to tackle war, unemployment, and oppression (110). This requires a scientific attitude, and Neurath is hopeful that in dark times, people will develop an even stronger yearning for freedom and science (130).

This inevitably takes time, because tradition and superstition need to be overcome. Scientists themselves are no exception; they, too, need to start from a place informed by tradition, from which they can move away only gradually. Where science will lead is, in the end, an open question. Perhaps it will change mankind, perhaps it can change the social order without changing humans.

But that problem is the concern of a more remote future. Without pursuing utopian ideals, men capable of judging themselves and their institutions scientifically should also be capable of widening the sphere of peaceful co-operation; for the historical record shows clearly enough that the trend has been in that direction on the whole and that the more co-operative man is, the more ‘modern’ he is. (132)

Unity of science

Neurath’s cosmopolitanism was connected to the distrust of metaphysical cookie-cutting he brought to the Vienna Circle and to his scientific thinking in general. His Anti-Spengler, written during his imprisonment in 1919, is an early example of this.[13] Spengler’s Untergang des Abendlandes, which described all of human history as the rise, flourishing and decline of cultures in analogy to the evolution of biological organisms, had come off the presses a year before. Predominantly negative scholarly reviews would do little to prevent Spengler from becoming a cultural sensation in the 1920s. Neurath diagnosis was that Spengler satisfied a desire for a closed world-view. In Neurath’s own eyes, the “unprecedented violation inflicted upon thought in this book” was extraordinarily dangerous. (143)

Neurath takes issue with Spengler’s claim that only groups smaller than humanity as a whole can have a ‘culture’; why, Neurath wonders, could a culture or civilization not pertain to humanity as a whole? (148) Unsurprisingly, Spengler’s idea of discrete and distinct – and indeed incommensurable – cultures is supported by very flawed reasoning. Neurath especially makes fun of Spengler’s Procrustean efforts to fit each cultural expression into a supposed essence or Ur-symbol.

“Is the ancient statue, or the figure on the vase isolated? – Of course, the Euclidean sensibility (Weltgefühl) demands it.

Is the ancient actor not isolated, but often accompanied by the choir – of course, because ‘[…] the choir that is always present, that chases away the fear of the boundless and empty even in the stage design – that is Apollinian.’” (172)

Like a theologian masterfully explaining every flea bite as evidence of God’s goodness, Spengler shows himself able to fit any phenomenon into the culture that generates it.

Similar concerns would later lead Karl Popper to propose refutability as a litmus test for genuine science. (At this same time, Popper was volunteering in Alfred Adler’s children’s clinic in Vienna, his impatience building with Adler’s tendency to see an inferiority complex everywhere.) Neurath, however, would not go that way, and even rejected falsificationism later. To him, there is an inescapable fuzziness to the concepts used in science and scholarship, and attempts to transcend it completely are not viable. In Anti-Spengler, Neurath presents (for the second time) his metaphor of having to reconstruct a ship on the open sea, never being able to start from scratch (184). He is not a rationalist rebuking a historicist; he is himself coming to the debate with a strong sense of historicity, and is remarkably open to the idea that there are differences that cannot be resolved by logic – in science as well as in culture.

He reminds the reader that in physics, there may be multiple internally consistent systems of hypotheses that satisfy a given system of facts, and continues to say that this is no less true for world views as a whole. Sometimes differences follow from logical fallacies or mistakes; but even when these are accounted for, variety may remain. The problem is not that Spengler is completely wrong, but that he hugely exaggerates the importance of this fact. It drives him to utter relativism, even leading him to say that what is true for us, is false for another culture. Really? “Is the mechanics, the geometry of Antiquity false for us? Was it false for the Arabs?” (188) Clearly, the answer is no. We live in the same world and we have a lot in common with other people; these commonalities are very important, and they are not erased by differences between historical cultures. They necessarily limit the relativist project. “The fact that the seasons follow each other, that fire burns and wine makes you drunk, are common to all world views.”[14] (190) The answer to Spengler’s fanciful history is not a more disciplined rationalism, but some measure of empiricism and common sense.

Neurath’s problem with big, abstract categories is that they hide from view concrete sources of unity and commonality.[15] When we sort cultural expressions into the essentially Apollinian or essentially Faustian, we use language to create divisions that are almost entirely fictional, but not powerless: prophecies could be self-fulfilling if prophets like Spengler were dedicated enough to bring them about (141). Science done right is the opposite of divisive prophesying; it is properly grounded in the concrete and the particular, which does not contain the abstract distinctions thought wrongly projects onto them. In this, for Neurath, lies the value of the logical empiricist project, which insists on weeding out concepts and claims that cannot be grounded in experience. No unsolvable riddles; no meaningless claims; no reliance on thought left to its own devices; but experiential knowledge and logical analysis, with an awareness of the ways in which language can lead our reasoning astray.

It is not, at least not for Neurath, an exercise in hyper-precision or formalism. We can speak freely, as long as we steer clear of concepts that have no way of being traced back to ‘protocol sentences’. Mind that there are a lot of those: ‘transcendental’, ‘categorical imperative’, ‘reality’, but also ‘norms’ and ‘intuitions’ end up on Neurath’s Index of forbidden words. When such free-floating concepts, untranslatable to a physicalist language, are weeded out, science will still be pluriform; but like the things it is about, it will not admit of unbridgeable gaps. Notably, the supposed chasm between the natural sciences and the humanities or Geisteswissenschaften melts away. To a new generation, this will simply be incomprehensible, as curious as the distinctions of medieval scholastics are to us. For though the arguments that support such a dichotomy are many, “they are always of the metaphysical kind, that is, meaningless.”[16]

Whatever concerns you now have about how art history is not the same as physics and all that, Neurath can tell you that if they are real, they will survive his anti-metaphysical purge. Take the role of empathy, introspection, or – a word with especially strong philosophical baggage – Verstehen (‘understanding’) in the humanities. You believe that you need to rely on introspection in order to properly understand the motivations of other people? Not a problem! In Neurath’s liberal understanding of protocol sentences, “I see a blue table in this room” and “I feel anger” are the same kind of observation. When you say Verstehen is important in the humanities, do you perhaps mean that you are sometimes angry and this helps you to recognize when other people are or were angry? Well, good; that is a kind of extrapolation very much compatible with physicalism. Just as long as you don’t get all starry-eyed about how Verstehen is something completely separate from scientific pattern-seeking. It is not magic.[17]

It is in this sense that all special sciences are subsumed in an Einheitswissenschaft, a unified science. There should be no hard borders in science that are not there in the world. To a well-informed Marxist, moreover, the interests behind an insistence on dichotomies are readily apparent: “as on the one hand the number of carefree physicalists is growing, now the number is also increasing of those whose tradition-laden metaphysical terminology provides the fitting superstructure to a tradition-laden societal current.”[18]

The effort to overcome dichotomies in science goes hand in hand with the effort to overcome them in society. Neurath’s thinking about the humanities and sciences was strongly intertwined with his efforts to further the notion of a unified science, as were his contributions to the Vienna Circle. His work with pictorial statistics and popular education has little direct overlap with that theoretical work. It does not take too much Spenglerian acrobatics, however, to conclude that it proceeded from the same archetype: a vision of modern humanity unified by a common grounding in, and grasp of, material things.

Neurath distrusted layers of abstraction that he believed severed our relation to those things – whether they be fanciful histories of clearly demarcated cultures, over-eager philosophical classification of the sciences, meaningless words and concepts we cling to, or even the money economy.[19] All these needlessly divide us even as the tendency of modernity is towards further unification. In his rebuttal to Spengler, this attitude led him to be very much on the side of common sense. In his co-operation with the Bolsheviks, maybe not so much. But rather than placing him on one side or another of some conceptual dividing line, go check out more of the amazing Isotype plates he and his collaborators left us.

[1] The text in the Münchener Neuesten Nachrichten is reproduced in the Max Weber Gesamtausgabe I.16. Zur Neuordnung Deutschlands: Schriften und Reden 1918-20. Wolfgang J. Mommsen ed. (Tübingen) 495.

[2] Weber to Neurath, October 4th, 1919. MWG II.10. Gerd Krumeich, M. Rainer Lepsius ed. (Tübingen) 798-800.

[3] Günther Sandner, Otto Neurath: eine politische Biographie (Vienna 2014) 48.

[4] Eduard Meyer, Geschichte des Altertums. (2. Auflage) I.1 (Stuttgart, Berlin 1907) 184-185 (quoted text here).

[5] Max Weber, ‘Kritische Studien auf dem Gebiet der kulturwissenschaftlichen Logik – I. Zur Auseinandersetzung mit Eduard Meyer’ (1905) in: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre (Tübingen 1922) 233.

[6] Nancy Cartwright, Jordi Cat, Lola Fleck, Thomas E. Uebel, Otto Neurath: Philosophy between science and politics (Cambridge University Press 1996) 176 (this part credited to Cartwright and Cat in the preface, p. x).

[7] Neurath, Einheitswissenschaft und Psychologie (Vienna 1933) 28 (here).

[8] Neurath, ‘Bildstatistik nach Wiener Methode in der Sowjetunion’ (Moskauer Rundschau, 1932) in: Otto Neurath, Gesammelte bildpädagogische Schriften. Rudolf Haller, Robin Kinross ed. (Vienna 1991) 207-209: 208.

[9] This and previous illustration from Christopher Burke, Günther Sandner, History and Legacy of Isotype (2024), published open access by Bloomsbury and available here.

[10] Günther Sandner, Otto Neurath, 193.

[11] Found via the reference in Sandner, Neurath, 194.

[12] Neurath, Modern man in the making (New York, London 1939).

[13] Page references to Neurath, ‘Anti-Spengler’ in: Otto Neurath, Gesammelte philosophische und methodologische Schriften I. Rudolf Haller and Heiner Rutte ed. (Vienna 1981) 139-196.

[14] Cf. Cartwright, Cat, Fleck, Uebel, Otto Neurath, 141.

[15] Cf. John O’Neill, ‘Unified science as political philosophy: positivism, pluralism and liberalism’, Studies in history and philosophy of science 34 (2003) 575-596: 587. “For Neurath it is as we move from the general and abstract and towards the particular and concrete that that which is common emerges.”

[16] Neurath, Einheitswissenschaft und Psychologie, 12-13.

[17] Neurath, ‘Soziologie im Physikalismus’ (1931) in: Michael Stöltzner, Thomas Uebel ed., Wiener Kreis: Texte zur wissenschaftlichen Weltauffassung (Hamburg 2006) 269-314: 289-290.

[18] Neurath, Einheitswissenschaft und Psychologie, 15.

[19] Cf. Robin Kinross’s remarks (with a caveat in the footnote) in his introduction to Neurath’s Gesammelte bildpädagogische Schriften. Rudolf Haller, Robin Kinross ed. (Vienna 1991) IX-XXIII: XIV.