by Michael Liss

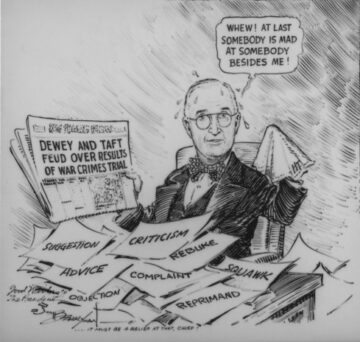

The defendants at Nuremberg had a fair and extensive trial. No one can have any sympathy for these Nazi leaders who brought such agony upon the world. —Thomas E. Dewey, Speaking about comments made by his fellow Republican, Robert A. Taft

Last month, I wrote about JFK’s Profiles in Courage and focused on one of the three Giants of the Senate, Daniel Webster, and his controversial and perhaps decisive role in the Compromise of 1850. This month, I want to talk about another of Kennedy’s picks, “Mr. Republican,” Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio, who led the conservative movement in the Senate for more than a decade.

The two men, Webster and Taft, couldn’t have been more different. Webster, perhaps the greatest orator in American history (Richard Hofstadter called him “the quasi-official rhapsodist of American nationalism”), had huge appetites, not all of them commendable. Robert Alphonso Taft was precise, restrained, and a stickler. A stickler for his conservative principles, a stickler on process and procedure, a stickler on policy issues such as isolationism (he was for it, comprehensively so) and the New Deal (positively, absolutely, unyieldingly no).

He was also possessed of a serious resume as both theorist and lawmaker in the Senate, a serious bloodline (his father, William Howard Taft, was President and then Chief Justice), and an even more serious ambition—the self-regard to think that he, too, should occupy the White House.

As you might imagine, Taft was not the only politician to think that of himself. It was an era of big challenges (The Great Depression and World War II among them) and big men. The biggest of all, FDR, already lived at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, and Taft sought the GOP nomination in 1940 to wrest it from him. Taft was in his prime, a talented legislator and bridge-builder to conservative Democratic Senators, but he was a fierce opponent of American intervention in Europe. Taft wasn’t alone in this—isolationism was closely associated with conservatism in the GOP, and two of his major rivals for the nomination, Michigan Senator Arthur Vandenberg and New York’s Governor Thomas E. Dewey, also were isolationists.

The problem with non-interventionism in the Spring of 1940, when the GOP string-pullers were preparing to gather in Philadelphia to pick their man, was those pesky Germans. On May 10, 1940, they launched an all-out assault on the low countries (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) and France. What followed was astonishing—a total victory for Germany and the utter disgrace of France. On June 14, 1940, 10 days before the Republican Convention began, the Germans marched into Paris. The French Government fled, and eight days later, an armistice was signed. A collaborationist regime was set up in Vichy (later in Clermont-Ferrand), with Maréchal Phillipe Pétain as nominal Head of State and Pierre Laval acting as the true head of the government. They took charge of the Unoccupied portion of France and proceeded to emulate their German overlords. They would fix the weakness of character that had laid France low. There’s a wonderful passage in the journalist and essayist A. J. Liebling’s The Road Back To Paris:

After a football calamity the professional coach, to save his reputation, sometimes implies his players lack courage. It would not suit Laval’s book to have too much of a scandal about war material, because his clients had supplied it. Nor could Pétain, [Generals] Huntziger, and Weygand afford to disparage generalship, because they had supplied that. And so Pétain started out to spread the libel of decadence against his own countrymen.

How could a Robert A. Taft, Isolationist Supreme, get the 1940 nomination in such a climate? The hill had just become steeper. It wasn’t that the non-interventionists suddenly wanted to saddle up in defense of Western democratic values. They didn’t. But the “Phony War” that had been in existence from the September 1939 German/Russian brutal carve-up of Poland had become a lot more real. Party insiders, many of them with a far better grasp of what the public was thinking than the potential candidates, sensed a growing concern, one that might eventually be reflected at the ballot box. Taft, Dewey, and Vandenburgh had been openly and sustainedly isolationist. Did that position resonate with a majority of the voters? Given the possibility of future American involvement, which of the three frontrunners would have the capacity to manage the challenge—particularly the perceived frontrunner Dewey, who was only 38 and had no foreign policy experience.

The situation was ripe for an outsider, and one emerged, the “Barefoot Boy of Wall Street,” Wendell Willkie. Willkie was a corporate lawyer and utility company executive who had never spent a single day in public office at any level. If experience was to be valued, why him over Dewey? Partly because his position on international involvement was consonant with one strain of Republican thinking that stretched back to Teddy Roosevelt. Mostly because he was fresh, and he had the secret sauce that winning politicians need—the backing of some of the most powerful figures in the media. Willkie positioned himself with the crowd that looked to support England as much as possible without actually committing troops, a position that, after France’s fall, became a lot more attractive.

Still, we are in the “Convention” era, where many of the delegates are likely closer to the party’s ideological core, and their traditional standard-bearers, than are the public at large. Willkie comes in with public enthusiasm and media support, but Dewey and Taft (Vandenberg is a lesser light) have more of the party insiders and loyalists.

First round of balloting, Dewey starts with a solid lead, Taft second, Willkie third. Over the course of the next three ballots, Dewey loses some altitude—not as a collapse, but gradually, and Willkie gains strength. Taft chugs along, picking up some former Dewey delegates. The fifth ballot is decisive. Dewey’s support completely evaporates. Taft picks up more votes, but he has a ceiling, while Willkie, who has both popular and institutional support, seemingly does not. On the sixth, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Dewey’s New York switch to Willkie, and the Dark Horse gets the prize—a contest with FDR that he is doomed to lose.

It is as close as Taft was going to get. In 1944, he stayed out, finding it difficult to navigate the crosscurrents between his prior non-interventionist stances (which he sustained until Pearl Harbor) and the reality of World War II. Dewey, who had moved center, was nominated and made a credible, if losing effort. By 1946, FDR gone and WWII over, the nation was souring on Truman, and Taft’s non-interventionist approach was less of a defining factor. 1948 could be his year, if he could get past Dewey.

JFK writes about a strain of pragmatism in Taft that occasionally left him on the wrong side of orthodoxy. Taft thought about things, proposed solutions on issues like health, education, and housing that were (and would continue to be) anathema to many in his own party. He was not what we would think of as a maverick. A more accurate description might be a situational truth-teller, the “situations” arising when his ideals clashed with reality and the “truths” were not always pleasant for his listeners to hear. All in all, an atypical politician, willing to take risks, but more, it appears, a man who was comfortable with his own ideas and didn’t feel like self-censoring himself.

In early Fall of 1946, things were going quite well for the GOP. Post-war demobilization had led to a very sharp drop in GDP. There was a weariness with Democrats in general and Truman in particular (his approval rating would be in the mid-30s by Election Day). We had won the war, but winning the peace seemed to be elusive, especially with an aggressive Russia fostering instability in Europe (over 1.5 million Germans passed over the border to the West in less than a year). Democratic prospects in the upcoming Midterms were grim, and the GOP saw an opportunity to sweep—Congress in 1946, the White House two years later.

This was the time for discretion, for avoiding the big mistake, the overt gaffe. The problem was that Robert A. Taft was troubled by something, and, in JFK’s recounting, when Bob Taft had something to say, he usually found a forum in which to say it. He had accepted an invitation to speak at Kenyon College on October 5, 1946, exactly one month before the Midterm Election, and it was there he would unburden himself. The topic, the verdicts in the Nuremberg Trials.

In “Justice and Liberty For All,” he delivered the following:

I believe that most Americans view with discomfort the war trials which have just been concluded in Germany and are proceeding in Japan. They violate that fundamental principle of American law that a man cannot be tried under an ex post facto statute.

The trial of the vanquished by the victors cannot be impartial, no matter how it is hedged about with the forms of justice. I question whether the hanging of those who, however despicable, were the leaders of the German people will ever discourage the making of aggressive war, for no one makes aggressive war unless he expects to win. About this whole judgment there is the spirit of vengeance, and vengeance is seldom justice. The hanging of the 11 men convicted will be a blot on the American record which we shall long regret.

In these trials we have accepted the Russian idea of the purpose of trials—government policy and not justice—with little relation to Anglo-Saxon heritage. By clothing policy in the forms of legal procedure, we may discredit the whole idea of justice in Europe for years to come.

There are deep questions here, some made for the philosophers among us. Let’s take them one at a time. First, the accusation that the defendants were being tried under an ex post facto statute. Here, Taft was making an excellent point—from the American perspective, such laws are explicitly prohibited by Article I, Section 9, Clause 3 of the Constitution (“No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed”). Both Madison and Hamilton, in the Federalist Papers, expressly rejected them. The four crimes charged at the trials were:

1. Crimes against peace: Planning, starting, or waging a war of aggression, or participating in a conspiracy to do so;

2. War crimes: Violating the laws of war, such as killing prisoners of war, murdering civilians, or destroying cities;

3. Crimes against humanity: Murder, enslavement, deportation, or other inhumane acts against civilians, or persecutions based on race, religion, or politics; and

4. Conspiracy to commit any of the above.

None of the above were ever explicitly reduced to law prior to the commission of the acts under which the defendants were charged. If your reaction to this is to say “’there ought to be a law,” I’m in complete agreement. But was Taft right? Let’s take a “strict constructionist” position and say absolutely and completely yes—but with one major exception noted below.

Second, two points: Taft was right that criminalizing the making of war does nothing to prevent…the making of war. We’ve been warring with each other since caves, and animal skins, and rocks and clubs. To paraphrase Einstein, we will continue warring with each other until we are back to caves and skins and rocks and clubs. It is absolutely “hell” and it won’t make one bit of difference whether you call it a crime or not. You don’t start a war if you think you will lose, and, if you win, you aren’t charging yourself. As to Taft’s claim that Nuremberg will be perceived as victor’s justice and victor’s vengeance, it’s a fair point, but a dead end that’s more a chasm. If the victors can never charge the losers with any crimes, including war crimes and crimes against humanity, then there never can be anything that, in practice, can be considered a crime. Accountability completely disappears. What do we say to the victims, or the families of victims? Hundreds of thousands, millions, tens of millions of victims? A loss of accountability leads to a loss of humanity, and an open door to more crimes. It is de facto unlimited immunity.

Third, whatever the flaws of the process, these were not Stalinist show trials. Telford Taylor, who served the International Military Tribunal as assistant to the Chief Counsel (to future Justice Robert Jackson) for the first trial of the High Command case, and later, after Jackson’s resignation, as Chief Counsel for the last 12 cases, acknowledged in The Anatomy Of The Nuremberg Trials multiple flaws in the formulation of the charges. In particular, he questioned the entire “Conspiracy” charge. He also noted mistakes in process, personnel disagreements, divergence on goals and approaches among the four prosecuting countries, and other issues. Still, Telford held fast to the idea that even Taft, backhandedly, acknowledged: The fact was that the Four Powers made efforts to afford basic due process to the defendants; the judges who heard the cases attempted regular order; and the defense mustered competent counsel. It is notable that Taylor’s first trial, which called for the General Staff of the Army and the High Command of the German Armed Forces to be considered criminal organizations, ended in acquittal.

Let’s jump back to Kennedy’s inclusion of Taft in one of his eight “Profiles”—his speech at Kenyon was courageous, regardless of its content, which he knew would draw political consequences. It is a very fair point. Taft was pounded, in the press, by opinion-makers, by friends at home, by Democrats, and even by members of his own party who knew a gaffe when they saw one. Bob Taft was going to say it, because Bob Taft believed it in, and Bob Taft possessed a moral compass. That wouldn’t mean it was good politics.

You can be anywhere on the spectrum regarding Taft’s position on the Nuremberg Trials and still be (partially) right. It is a moral decision on accountability—does the importance of strict adherence to the rule of law outweigh the urgency of society to express disgust for, and inflict punishment on, those who commit truly bestial acts. Taft made his choice and suffered the slings and arrows for it, both at the time and two years later, in 1948, when Dewey trounced him for the nomination.

Taft’s conduct reminds us of the essentialness of both a moral center and sound thinking in the people we select to lead us. We vest them with great power and need them to apply their best judgment to matters of national importance. We can’t expect them to be anything but imperfect people. The idea that successful politicians have never played the game, never cast votes they knew were wrong but their Party needed them, or never looked at sizable campaign contributions as possible requests for services rendered is an absurdity. Too much purity leads to a return to private life. Kennedy is explicit about this in Profiles and he’s absolutely right. When we pick a President, or any other high official, we must choose. Does this person have the capacity to make difficult choices when right and wrong are clearly apparent—and does he (or she) have the capacity to choose the lesser-of-two-evils path when absolute right or wrong are less clear? Is he willing to put the needs of the people over his or her own personal/political benefit? Does he seek justice or vengeance? Can he moderate his own worst impulses because he knows he has a higher duty? It is human to seethe, to want to inflict punishment on someone who wrongs you, to take the road of the disproportionate response. Presidents have to be better than that.

With all the challenges, all the human failings, even all the possible errors in judgment (Taft was surely wrong on non-intervention as a response to Hitler), we have to hold to a standard that demands as much as we can get. In the end, integrity—personal, intellectual, moral—certainly matters.

The American Presidency is the most impactful job in the entire world, except for one thing—the collective obligation of the voters to participate as citizens and choose their leaders, purposely and wisely. Our system, our freedoms, even the continuation of our democracy, rely on it. Kennedy himself, in speaking at Emory in 1963, remade the point:

But this Nation was not founded solely on the principle of citizens’ rights. Equally important, though too often not discussed, is the citizen’s responsibility. For our privileges can be no greater than our obligations. The protection of our rights can endure no longer than the performance of our responsibilities. Each can be neglected only at the peril of the other.

In the end, it is upon us, as citizens, to see the way and choose it. To do anything less would be an abrogation of a sacred duty, a Profile in Cowardice.