Broken symmetry: a high-altitude airliner above Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Broken symmetry: a high-altitude airliner above Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Jeroen van Baar

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

In recent years, scientists have started to uncover how this ‘gut microbiome’ shapes a variety of health outcomes including obesity and depression. For instance, when researchers transplanted fecal matter from depressed humans to rats, those rats started showing signs of depression themselves. We’re still unsure why this happens—it could have to do with the production of neurotransmitters, which depends on how food is processed—but the gut microbiome forms a promising horizon of health science.

This has raised the obvious question why the biome in your belly looks the way it does. Where did it come from? We normally assume that the microbiome is mostly shaped by the food we eat. But a new Nature study provides a radical refinement of this story: our social interactions can shape the microbial communities living inside us.

The study involved mapping the social networks and sequencing the microbiomes of 1,787 adults in 18 isolated villages in Honduras. Participants were asked to self-collect stool samples, which were stored in liquid nitrogen and shipped to the USA for analysis. A detailed survey and photographic census helped participants identify their social connections, including their friends and family.

Analyzing the data, the research team found that the gut microbiome looked the most similar between members of the same household: they shared up to 14% of the microbial strains in their guts. However, even friends who see each other regularly shared about 8% of strains, while strangers from the same village shared only 4%. Microbiome similarity even extended to friends of friends, forming potential transmission chains that spread strains within communities. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

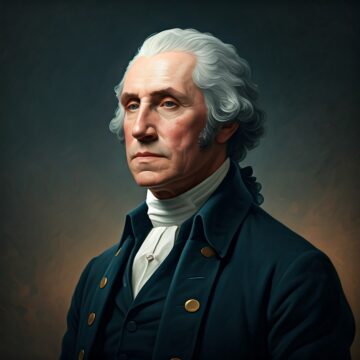

The Founding Fathers aren’t much in fashion among liberals these days. A good friend of mine has been trying to get a novel about Thomas Jefferson published for three years. He has approached more publishers than he can care to name, publishers of all sizes, reputations and political persuasions. He tells me that while most mainstream, as well as niche publishers, have turned his manuscript down, a small number of right-wing houses that typically publish conservative polemic are deeply interested.

My friend’s problems with publishing Jefferson mirror the liberals’ problem with the Founding Fathers in general. At best they are dismissed as outdated dead white men, and at worst as evil slaveholders. But as an immigrant who came to this country inspired by the vision these men laid down, I don’t feel that way. Neither does my 4-year-old who proudly dressed up as George Washington, of her own accord, for Halloween last year. She stood proudly in her little tricorne hat and blue colonial coat, her face full of determination, as if she too was leading an army (she was particularly inspired by the stories I told her of Valley Forge and Washington’s crossing of the Delaware). Both she and I believe that while these men’s flaws were pronounced, and vastly so in some cases, the good they did far outlives the bad, and they were great men whose ideals should keep guiding us. More importantly, I believe that a liberal resurrection of the Founding Fathers is in order today if we want to fight the kind of faux patriotism foisted on us by the Party of Trump (“POT”. We can no longer call his party the Republican Party — that party of Dwight Eisenhower, of Ronald Reagan, of respect for intelligence, fiscal responsibility, international stewardship and opposition to real and not perceived evil, is gone, kaput, pushing up the daisies, as the memorable sketch would say: it is an ex-party).

But we must remember the times in which they lived if we want to free ourselves of the disease of presentism. As wealthy Virginia planters, it would be virtually impossible to imagine Washington or Jefferson not owning slaves. Their acceptance of slavery was, however evil and anachronistic it seems to us, common among people of their era. However, their ideas about free speech, religious tolerance, separation of powers, and individual rights were not. In other words, as Gibbon said about Belisarius, “His imperfections flowed from the contagion of the times; his virtues were his own.” In addition, it is important to not bin “The Founders” in one homogenous, catch-all bin. Washington freed his slaves and was a relatively beneficent and enlightened master for his times, loathe to participating in the wrenching practice of separating families, for instance; Adams and twenty-two of the signers of the Declaration of Independence did not own any at all; Franklin later became an abolitionist; Jefferson was probably the biggest culprit – not so much because he owned many slaves but because the gap between his soaring rhetoric and the reality at Monticello, not to mention his relationship with Sally Hemings, is glaring. To recognize these differences between the Founding Fathers is to not excuse their practices; it is to recognize the possibility of human improvement and the fact that in every age there is a spectrum of men and morality.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait Against Table Mountain. August, 2019.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait Against Table Mountain. August, 2019.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Tim Sommers

Why have a democracy? Because democracy is always right.

There are two kinds of arguments in favor of democracy: intrinsic and instrumental. Intrinsic arguments try to show that democracy is good in-and-of-itself – and not as simply a means to some other end or ends. Instrumental arguments try to show that democracy is good because it leads to some good.

There are two main kinds of intrinsic arguments: those based on liberty and those based on equality. The most straight-forward kind of liberty argument says that we should be free, but to be free means not only to govern ourselves, but to have some control of our larger social and material environment. Democracy gives us that control. The trouble is that in actually existing democracies very, very few people are able to exert any real influence on society or their material conditions via the political process. Democracy does not make most of us free, at least in this way.

Here’s a different kind of liberty argument. We all have certain basic rights. Among the basic rights, liberties, and freedoms we possess in a liberal democracy – freedom of religion, free speech, the right to the rule of law, etc. – there are also rights of political participation – political speech, a right to free assembly, etc. What does this kind of pro forma right to some kind of political participation really amount to, though?

There’s no right to vote in the US Constitution. And Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem shows there is no way of counting votes that can satisfy all of the seemingly simple and reasonable conditions voting must bear. To oversimplify a bit, there is no way of voting that always gives us an answer, always depends on the input of more than one person, gives a way of deciding between candidates based on voting (and nothing else), and insures that the choice between any two candidates is independent of how the voter feels about other candidates.

Fortunately, there are also equality-based arguments for democracy. Many political philosophers have argued that democracy is a way of treating people equally. But lotteries treat people equally too. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

Much philosophical writing about food has included discussions of whether and why food can be a serious aesthetic object, in some cases aspiring to the level of art. These questions often turn on whether we create mental representations of flavors and textures that are as orderly and precise as the representations we form of visual objects.

Much philosophical writing about food has included discussions of whether and why food can be a serious aesthetic object, in some cases aspiring to the level of art. These questions often turn on whether we create mental representations of flavors and textures that are as orderly and precise as the representations we form of visual objects.

The claim that we do not form such ordered, mental representations is central to the view that food and drink cannot be serious aesthetic objects or works of art. The reason is that genuine aesthetic experience requires the apprehension of form or structure. In the absence of structured representations there is no form to apprehend. (See Part 1 of this essay for a more detailed account of mental representations of aroma.)

I want to argue that the skeptics have a point although they draw the wrong inference from it. Our flavor experiences do, in fact, rest on weak representations. They lack the stable, detailed, clearly identifiable objects that vision typically yields. However, these weak representations allow for the apprehension of a different kind of structure, what I shall call a nomadic distribution (or continuously changing structure), and it is in fact this nomadic distribution of flavor that enables the aesthetic experiences characteristic of our engagement with food. The main point to draw from this is that cuisine is about transformation, one thing becoming another, and it is ill served by theoretical perspectives that rely on mental representations with firm identity conditions.

The explanations for why flavor and aroma are weakly representational fall into three categories—flavors are ephemeral, ambiguous, and difficult to remember with precision. Read more »

In perilous times we join the otherworld,

the one that’s outside

our bubble

who’s driving this bus?

who’s at the helm?

who jiggles the joystick?

we man our posts

we soothe ourselves

but one day must come to terms:

I saw a cormorant, wings spread

drying herself in the wind after lunch

oblivious to the dilemma of our recklessness

but snared nevertheless in its reach

but time itself is oblivious,

and space

so, who?

Jim Culleny

7/10/19

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Mike Bendzela

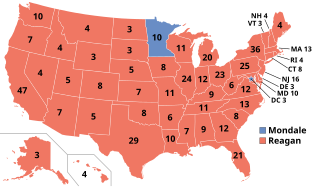

I lie on a futon in a little room tucked in a turret of an old funeral home-turned-apartment building in Binghamton, New York, listening to election returns coming in over my clock radio. It is a Tuesday night in 1984, the year of Orwell’s never-ending fever dream. Madonna and Prince and Michael and Bruce play incessantly on the radio between election reports. The unfolding AIDS epidemic is a thing no one wants to talk about: A friend, a PhD candidate in poetry, is sick in faraway Florida, but none of us in the department even knows about it yet. He will be dead in six months.

I am a year into my stint in graduate school. (Two years will be more than enough for me.) The path to my master’s degree in English has been a circuitous one, even tortuous: As an undergraduate, I started out in geology with a little climatology, detoured into art and design for two years, then ended up studying American literature. But I have never lost my love of the Earth sciences.

Ronald Reagan, at 73, is the oldest candidate ever to run for election — or, in this case, re-election — as President of the United States, against . . . What’s his name again? This election marks (I firmly believe) our last chance as a civilization to change course and sail towards a Green Future, an inkling of which we saw with President Jimmy Carter. I do not know if What’s-his-name is the answer, but we all know Reagan ain’t. One term could be a fluke. A second, collective suicide.

Several months hence, the great science communicator, Carl Sagan, will say to the United States Senate, “If you don’t worry about it now, it will be too late later on.”* His talk is a plea to those in power to start controlling carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels. The concentration of atmospheric CO2 in 1984 is 344 parts per million and the global temperature anomaly a barely noticeable +0.40° Celsius.* Carbon dioxide concentration MUST be kept below 350 ppm, or the planet will heat up, creating havoc. And there are other pollutants to worry about. And also oil depletion, deforestation, ocean acidification, wildlife habitat loss, over-population. A collapsing civilization does not seem far-fetched.

False alarm! It is Morning in America.* Read more »

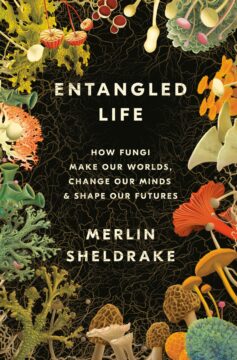

by Adele A. Wilby

Recently I stepped into the underworld of fungi in Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life: How Fungi Make our Worlds, Change our Minds and Shape our Futures. His book took me to an ancient world, tirelessly and inconspicuously working away and doing its vital job of literally interlacing the planet and holding it together to make life sustainable. The entry into this curious world was through the rather unassuming life form that most of us are more accustomed to eating than we are to learning about its existence: the mushroom.

Mushrooms are, for most of us, just another source of food, or indeed choose the wrong kind to consume and the adverse effects are likely to be more dangerous than delicious. They are though, fruiting bodies of fungi whose appearance on the surface is aimed at the reproductive role of dispersing millions of spores into the atmosphere to secure their existence.

Colourful mushrooms of all sizes and shapes poking their heads up from the leafy undergrowth of a woodland or forming colonies of various architectural designs on dead trees, have never failed to draw my attention during my wanderings through wooded areas. Fascinated by these humble looking elegant protuberances that decorate the forests, on some occasions I have taken the time to count the varieties I have seen and found several different types on any one day. But as I learned from Sheldrake, my enthusiasm for the diversity of the mushrooms I observed was quite trivial in comparison with the numbers of fungi on the planet: there are, literally, millions of species throughout the world. Read more »

by Andrea Scrima

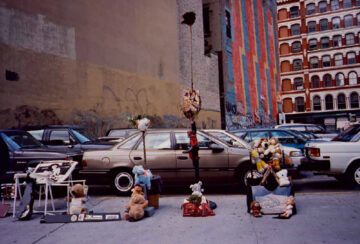

I recognized the corner immediately: it was right next to Cooper Union, on Lafayette Street in downtown Manhattan. There used to be a large parking lot on the other side of the street, where passers-by occasionally happened upon a colorful bricolage cobbled together from stuffed animals and clothes, discarded household items, deformed umbrellas, and battered car parts. These strange and playful conglomerations looked as though the bric-a-brac and refuse had been plucked together by some invisible furious force to house a spirit or daemon. They were, of course, carefully composed works by the late African-American artist Curtis Cuffie, one of the many ephemeral assemblages he created in the streets of downtown New York in the 1980s and 1990s.

Cuffie installed his improvised ensembles of found objects on fences, window grilles, sidewalks, and traffic signs in Cooper Square, the Bowery, and elsewhere; they were always temporary, and only a few of his works have survived. Cuffie periodically lived on the streets around Cooper Square and his homelessness must have made his emotional tie to the treasures he found and wheeled around in shopping carts all the more urgent. Most of the works he created from this repertoire of materials were abstract, shrines that seemed to grow out of the flotsam and jetsam of a city in constant transformation; seen from a passing car, they flashed in the sideview mirror like otherworldly apparitions. But there were also figurative sculptures: ragged garments strung on wire and string and adorned with hats or wigs became animated spirits on a secret mission. Today, the few remaining works by Cuffie that were not taken down and destroyed by the police or street cleaners are shown and sold in the pristine white spaces of uptown Manhattan galleries, stripped of their context and also, perhaps, a good deal of their meaning. Read more »

by Steve Szilagyi

My favorite place on Earth is Niagara Falls. I refresh my spirit there. Standing on the very brink, my chest pummeled by the roar of millions of gallons of fresh water plunging into the abyss, I feel at one with figures like Margaret Fuller, Charles Dickens, and Mark Twain, each of whom recorded their humbled awe at the spectacle. I throw my mind into the past and imagine countless generations of Native Americans standing on the brink of the Falls and wondering, as many do today: where is all this water going?

Well, I’ll tell you where it goes: down the Niagara Gorge, into Lake Ontario, into the St. Lawrence Seaway, and finally to the Atlantic Ocean, where it mixes with the saltwater and is, for all practical purposes, wasted.

Now I’ll tell you where it isn’t going: it isn’t going to the showerhead in my luxury Niagara Falls hotel room. Even though I can look through my window and see 44,500 gallons of fresh water tumbling over the brink every minute, when I step into my marbled bathroom and turn on the shower, I stand under the same strangled trickle I’d get in a cheap motel outside Salinas, California, or another city with severe water use restrictions.

Primal pleasure denied. I don’t need to sell anyone on the satisfaction of a good, strong shower—hot, but not too hot, slightly stinging, and thoroughly cleansing of both body and soul. Yet this primal pleasure has not been widely available since 1992, when the U.S. Energy Policy Act mandated that new showerheads sold in the country not exceed 2.5 gallons per minute.

The Energy Policy Act makes sense for places like the American West, where the combination of climate change, cattle farming, and almond growing has created a dire water situation. But Niagara Falls? Read more »

by Paul Braterman

This book is a delight. Drawing on a deep love of her subject matter, the author interweaves descriptions of a sequence of rock types with the story of her own personal and professional life. An extremely difficult feat to bring off, but Marcia Bjornerud (M) manages to do this without artificiality or mawkishness, drawing on historical and philosophical insights whose origins are hinted at throughout the text, and explaining complex concepts in lucid and enjoyable language. The only thing I did not like about the book is its appearance, which for me fails to suggest the hard-won insights that it is so successful in conveying.

M began her training in the early 1980s, at an interesting time, when the community of geologists was still absorbing the implications of plate tectonics, and geology was changing from a descriptive to an explanatory science. This was also when, despite the best efforts of the fossil fuel companies, predictions of global warming were beginning to seep into public awareness. A difficult situation for a socially aware geologist, since these same companies are going to be the main employers of her students.

She was established in what most people would regard as a successful academic career, having earned tenure at an unnamed but easily identified major Midwestern research university. But she was not happy, either with the location (in the middle of a vast expanse of one of the few kinds of rock that she really seems to find boring) or with the atmosphere of the place. And so, despite having got away with such subversive activities as smuggling a mention of Gaia into a lab manual chapter on biogeochemistry, and devising undergraduate classes that actually taught students something, she decided that she needed to move. Easier said than done. She was too far along in her career for ordinary entry-level positions, but not yet advanced enough for senior appointments. So she made the extraordinary decision to apply for a teaching job at Lawrence University, a tiny private liberal arts college in Wisconsin, and we must be glad that she did so.

Lawrence is clearly a very special kind of place. It educates not only its students (all 1500 of them), but its faculty, by involving all of them in its “great books” programme. And there, released from the treadmill of writing papers to gain grants to fund students to collect data to write papers, she has been able to explore at will and meditate on her findings, in the occasional specialist publication but also other outlets such as newspaper articles, and in a series of books including Timefulness, which I reviewed here earlier, and the present volume. (All this despite an unusually demanding family situation, and the responsibilities of rebuilding her department.) Read more »

by Richard Farr

The tree was immense even by local standards: a western red cedar that might have been a thousand years old. A botanist would want to measure it; I only wanted to touch its wrinkled face, or kneel among the roots and capture a dramatic snapshot looking up along the trunk. But it was fifty paces away and I couldn’t get there.

The tree was immense even by local standards: a western red cedar that might have been a thousand years old. A botanist would want to measure it; I only wanted to touch its wrinkled face, or kneel among the roots and capture a dramatic snapshot looking up along the trunk. But it was fifty paces away and I couldn’t get there.

We were 300 miles northwest of Vancouver, as the raven flies, on one of the countless islands of the Great Bear Rainforest. The Great Bear covers 25,000 square miles of British Columbia’s Central Coast, which makes it about the size of Sri Lanka. You can get into it by road, sort of, if you take a long, long detour around the back of the coastal mountains to the Bella Coola valley. But water has always been the real road in this maze of islands and inlets, so instead we drove our kayaks to Port Hardy, on the northern tip of Vancouver Island, rolled them onto the ferry, and rolled them off five hours later at the geographical and spiritual heart of British Columbia’s Central Coast, the Heiltsuk community of Bella Bella.

We paddled for twelve days. From the water we saw cormorants and sea otters beyond counting; porpoises; humpbacks. But the land seemed eerily empty, aside from a mink the color of salted chocolate that scampered past my feet one evening. Clawed prints in the sand. A few distant howls in the night. But the bears and wolves, and no doubt many other creatures, were perfectly hidden by the most dominant form of life, tens of millions of trees.

They cover almost everything. On most of the islands, whether fifty square miles or the size of a room, the forest approaches the water like a shoulder-to-shoulder army marching over a cliff, the edge marked by a constant slow-motion falling. The only shore is a yellowish ring of hand-shredding, barnacle-encrusted boulders, fortifications so uniform that it can be hard to finding even the sketchiest place to land. Camping is possible only because some islands have pockets of white sand beach.

Here, for me anyway, was a strange and arresting new experience of wilderness. Read more »

My favorite tree next to the river Eisack in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Katalin Balog

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern. —William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Laments about young people’s declining mental health, their inability to read novels, contemplate art, or simply pay undivided attention to anything at all have reached a panicky intensity lately. Not being particularly young, I can distinctly remember a time when things were less dire in this regard (except for the mental health part, having grown up in Eastern Europe…). We loved the films of Antonioni, Bergman, Tarkovsky, and Tarr, whose slow pace, for the most part, would be out of the question in today’s film industry. We were able to entertain ourselves without being entertained.

I propose that there is a common thread to these problems, and of course, they don’t only afflict the kids. We are all losing our ability to engage in a way of thinking I call contemplation. Young people are in an especially difficult place: whereas older people still remember and possess that ability to some degree, younger people have not had much opportunity to pick it up in the first place. And while it always required a certain amount of leisure and cultivation, a certain amount of groundedness and prosperity, today, contemplation is widely underappreciated and is in decline.

Contemplation is more than simply having experience; not all experiencing counts as contemplation – otherwise, we would all be automatically non-stop contemplators! In contemplation, experience is “held” in attention and explored without a particular goal in mind. This is different from other forms of attention deployed in thought or perception, which are fast-moving and task-oriented. Contemplation happens in small ways every time we stop to appreciate the world as we experience it, every time we are present for what is happening in a deliberate fashion, rather than breezing through in automatic pilot (or being absorbed in thought to the exclusion of experience). This could be a momentary lingering on someone’s body language or the way they express themselves. It could be an experience of merging with the natural environment. It could be a state of reflection reading a novel or poem. It could be just sitting and mulling over some experience of the day. Thomas Nagel said that there is “something it’s like” to have an experience. Contemplation then is attention to what it’s like. Read more »

by Mark Harvey

“Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” –HL Mencken

I’ve always loved Winston Churchill’s comment about his political rival Clement Attlee: “He’s a modest man, a lot for which to be modest.” Churchill himself was not a modest man, and when asked how he thought history would treat him, he responded, “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.” He did go on to write a significant historical tome titled The History of the English Speaking People and even won the Nobel Prize in literature for his writing and oratory. You could turn the phrase on its head to describe Churchill, the man who saw Hitler’s evil early on and helped lead the allies through World War II: he’s an arrogant bastard, and a lot for which to be arrogant.

America’s arrogance and individualism seem to be at a grotesque peak right now with our choice of president in the recent election. We’ve chosen perhaps the most arrogant man in history for a second term in the Oval Office. This is a man who compares himself to Lincoln and Washington, hinting that he might be greater than either one. Take a seat, Jesus Christ, your miracle work pales in comparison to his Eminence at Mar-a-Lago.

But it hasn’t always been so, and it’s good to remember those great American leaders who exhibited a healthy modesty, even those who had nothing to be modest about.

Our very first president, George Washington, though a snappy dresser, was modest to a fault. Upon being made commander of the Continental Army in 1775, he said, “I beg it may be remembered, by every gentleman in this room, that I this day declare, with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.” Washington was, of course, up to the task, probably more than any man alive at the time. Without his warring capacity, we might all be eating mince pies and Cornish pasties.

But he truly had little stomach for public appointments and certainly did not seek the presidency. After the long and bloody war fighting the British, Washington’s sole desire was to return to his wife, Mount Vernon, and his love of farming, or, as he put it, “to the shades of my own vine and fig tree.” Read more »

Julya Hajnoczky. Boletinellus Merulioides, 2021.

Julya Hajnoczky. Boletinellus Merulioides, 2021.

Archival pigment print.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Bill Murray

Maybe it’s defeat in a short, sharp war far from home. Maybe Russia captures Ukraine, or China attacks Taiwan. Maybe nothing happens yet, maybe it’s four or eight years away, but however the big change comes we’ll all agree the signs were there all along.

Maybe it’s defeat in a short, sharp war far from home. Maybe Russia captures Ukraine, or China attacks Taiwan. Maybe nothing happens yet, maybe it’s four or eight years away, but however the big change comes we’ll all agree the signs were there all along.

Our executive branch is hobbled by an exhausted leader. Our legislative branch is unable to legislate and our Supreme Court has found sudden delight in partisanship.

This election was exhausting. We just got a lesson in how riven America is, culturally and politically. Until President Biden stood down, our political parties had both put up candidates unfit for the presidency. And yet one of those candidates is now set to govern.

After months of total immersion in the campaign, and in place of recriminations and hand wringing, this might be a good time to put down our partisanship and consider America’s place in the world.

As soon as we raise our heads from our screens it’s clear: the United States is promising the world more than it is prepared to deliver. It has no business claiming it can defend Europe against Russia and Taiwan against China at the same time. You know it, every international player knows it, and if America continues to claim that it’s so it will be called out soon enough.

So we need to make some changes. This was going to be true whichever party won the election, and if America gets the coming decade wrong, time-tested elements of the US-underwritten world operating system (US OS) will struggle to endure.

I argue not from ideology but from pragmatism, and maybe a bit of dated idealism. Read more »