by Monte Davis

Only a moment ago he asked Mrs. Murdoch to fetch his parents. Now all three are standing in the kitchen doorway, watching the reflected sunlight that skitters above the stove, across the ceiling. When he notices the adults, he mischievously directs it into their eyes. John Clark Maxwell squints and raises a hand to block the glare, but his voice is indulgent. “What are you up to, Jamesie?”

“It’s the sun, papa. I got it in with this tin plate.”

Before the afternoon is over, Jamesie will roll the plate around the pantry floor until Mrs. Murdoch sends him outside; beat it as a drum, marching against Napoleon with the Iron Duke; fill it with pink granite pebbles; empty it again, set it afloat on the duck pond, and bombard it with pebbles until it is swamped by the interlacing waves.

1

The antenna turns slowly against the spin of the earth, tracking a galaxy eight billion light-years away. That far away, that long ago, the galaxy’s core was exploding with unimaginable violence. Here and now, the radio outburst is almost lost in background noise. Penzias and Wilson thought that the noise in their antenna might be caused by pigeon droppings. Instead, it was the echo of the Big Bang.

Where did the Big Bang go? Into waves.

Waves in what?

In the field. The electromagnetic field. Maxwell’s field.

What is the field?

It’s like the water for ocean waves. It’s like the air for sound waves. It’s like the earth for seismic waves. It’s like…

No, it isn’t. We’ve just forgotten how strange it was.

Penzias and Wilson weren’t the first to have noise problems. Their radio astronomy traced back to Karl Jansky, trying to understand annoying static from nowhere on earth. Which went back to Marconi, who made a revolution out of a laboratory curiosity. Which went back to Heinrich Hertz in a darkened room at Karlsruhe, adjusting the gap between two brass spheres until he saw a spark: the first deliberate radio message. Which was only part of a message from James Clerk Maxwell that is still unfolding. Read more »

1.

1. 2.

2.

There’s a lot going on right now. Lowlights include racism, misogyny, and transphobia; xenophobia amid undulating waves of global migrations; democratic state capture by right wing authoritarians; and secular state capture by fundamentalist Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu nationalists.

There’s a lot going on right now. Lowlights include racism, misogyny, and transphobia; xenophobia amid undulating waves of global migrations; democratic state capture by right wing authoritarians; and secular state capture by fundamentalist Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu nationalists.

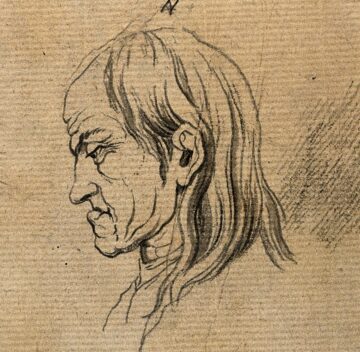

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

Sughra Raza. Science Experiment as Painting. April, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Science Experiment as Painting. April, 2017.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous