by Mark Harvey

“Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” –HL Mencken

I’ve always loved Winston Churchill’s comment about his political rival Clement Attlee: “He’s a modest man, a lot for which to be modest.” Churchill himself was not a modest man, and when asked how he thought history would treat him, he responded, “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.” He did go on to write a significant historical tome titled The History of the English Speaking People and even won the Nobel Prize in literature for his writing and oratory. You could turn the phrase on its head to describe Churchill, the man who saw Hitler’s evil early on and helped lead the allies through World War II: he’s an arrogant bastard, and a lot for which to be arrogant.

America’s arrogance and individualism seem to be at a grotesque peak right now with our choice of president in the recent election. We’ve chosen perhaps the most arrogant man in history for a second term in the Oval Office. This is a man who compares himself to Lincoln and Washington, hinting that he might be greater than either one. Take a seat, Jesus Christ, your miracle work pales in comparison to his Eminence at Mar-a-Lago.

But it hasn’t always been so, and it’s good to remember those great American leaders who exhibited a healthy modesty, even those who had nothing to be modest about.

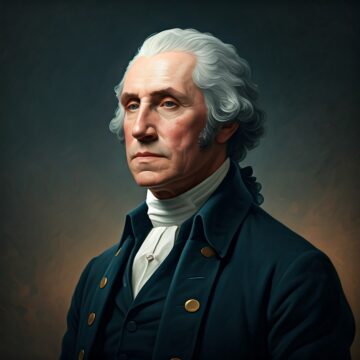

Our very first president, George Washington, though a snappy dresser, was modest to a fault. Upon being made commander of the Continental Army in 1775, he said, “I beg it may be remembered, by every gentleman in this room, that I this day declare, with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.” Washington was, of course, up to the task, probably more than any man alive at the time. Without his warring capacity, we might all be eating mince pies and Cornish pasties.

But he truly had little stomach for public appointments and certainly did not seek the presidency. After the long and bloody war fighting the British, Washington’s sole desire was to return to his wife, Mount Vernon, and his love of farming, or, as he put it, “to the shades of my own vine and fig tree.” Read more »