by Katalin Balog

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern. —William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

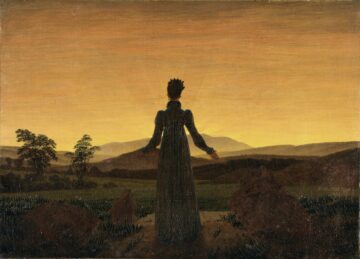

Laments about young people’s declining mental health, their inability to read novels, contemplate art, or simply pay undivided attention to anything at all have reached a panicky intensity lately. Not being particularly young, I can distinctly remember a time when things were less dire in this regard (except for the mental health part, having grown up in Eastern Europe…). We loved the films of Antonioni, Bergman, Tarkovsky, and Tarr, whose slow pace, for the most part, would be out of the question in today’s film industry. We were able to entertain ourselves without being entertained.

I propose that there is a common thread to these problems, and of course, they don’t only afflict the kids. We are all losing our ability to engage in a way of thinking I call contemplation. Young people are in an especially difficult place: whereas older people still remember and possess that ability to some degree, younger people have not had much opportunity to pick it up in the first place. And while it always required a certain amount of leisure and cultivation, a certain amount of groundedness and prosperity, today, contemplation is widely underappreciated and is in decline.

Contemplation is more than simply having experience; not all experiencing counts as contemplation – otherwise, we would all be automatically non-stop contemplators! In contemplation, experience is “held” in attention and explored without a particular goal in mind. This is different from other forms of attention deployed in thought or perception, which are fast-moving and task-oriented. Contemplation happens in small ways every time we stop to appreciate the world as we experience it, every time we are present for what is happening in a deliberate fashion, rather than breezing through in automatic pilot (or being absorbed in thought to the exclusion of experience). This could be a momentary lingering on someone’s body language or the way they express themselves. It could be an experience of merging with the natural environment. It could be a state of reflection reading a novel or poem. It could be just sitting and mulling over some experience of the day. Thomas Nagel said that there is “something it’s like” to have an experience. Contemplation then is attention to what it’s like.

‘Reflection’ is another word for this; I nevertheless prefer ‘contemplation’ for its closer association with deliberate attention. This association also makes it possible to distinguish it from rumination, which is an obsessive and automatic rather than a deliberate and voluntary process. Of course, it is hard to sort thinking neatly into categories; one style of thought might bleed into another. But I hope the idea is clear enough to be useful.

Value and experience

Contemplated by different people, [the] same glass can be a thousand things, however, because each man charges what he is looking at with emotion, and nobody sees it as it is but how his desires and state of mind… see it. (Luis Buñuel)

All primordial comportment toward the world….is a primordial emotional comportment of value-ception. (Max Scheler)

Before I say more about the significance of contemplation, let’s consider the connection between experience and value. We come to appreciate the value of people, activities, or objects, their appeal, depth, significance, etc., in dwelling on our everyday phenomenal experience.

The flower appears pale blue, fragrant, with a sharply defined shape; if I pay proper attention, it also appears delicate, refreshing, and delightful. Such sensuous features give the world its significance at the most fundamental level. Freshness or beauty is as much part of the content of my experience of the flower as is its color and shape. In experience, things can appear beautiful, kitschy, sublime, horrific, appealing, or repulsive. Perhaps all normal experience is evaluative – things don’t tend to be experienced as entirely neutral.

Our primary contact with values is through experience. This might seem an overly bold claim. To see if it is right, imagine a person, let’s call her, in a twist on Frank Jackson’s famous philosophical thought experiment, Insensate Mary (I discussed a variant of this scenario in these pages). Though she perceives things much like normal people – e.g., colors, shapes, textures, etc. – she lacks the sensuous appreciation of value.

The thought experiment relies on the idea that perceptual and evaluative content can come apart. It seems likely that they can vary somewhat independently. We all experienced walking the same streets or looking at the same objects, experiencing them wildly differently depending on our mood or general state of mind. What was drab and uninspiring one day might be exciting another day. To take an example that is more directly relevant, consider the way morphine affects pain: it apparently leaves the sensory content intact but entirely removes the affective component, the awfulness of pain.

Insensate Mary, then, when she sees a roadside accident, has no “gut reaction” to it: she feels no aversion, no horror, no sadness, or, as the case might be, no morbid curiosity. When she is with her loved ones, she feels no love or joy from their presence. She has never experienced the myriad ways something can be painful or joyful. Insensate Mary does not only lack an understanding of pain and joy but also of the badness of pain and the goodness of joy. She is incapable of forming a conception of and orienting toward value.

But could it turn out that these values are not “inherently” sensuous, in other words, that, even in the absence of relevant experience, she could still form some other, objective conception of them? And more importantly, that she could still value things? This doesn’t seem to be possible. Suppose, for example, that her AI assistant trains her to pick out beautiful things based on objective markers. She might even develop all the right dispositions towards beauty (spend time with it, etc.).

Still, her concept of beauty would not only be different, it would be defective. She wouldn’t be attracted by it like normal people are and her actions toward it wouldn’t make sense. She would recognize beauty and seek it, but not for the right reasons, that is, not out of desire, attraction, longing, or passion, all reasons with a subjective, experiential component. Mere recognition and a disposition to act are not enough to form value concepts, for the simple reason that valuing itself requires subjective experience – the visceral experiences of attraction and recoil they produce in us. The upshot is that affective insensitivity cannot be compensated by objectivity. Only if we view ourselves as robots can it seem that valuing could take place in the absence of any experience of it.

The importance of contemplation

Grasping values

Since value is grounded in experience, contemplation leads to more, and more accurate knowledge of value. In Sinan Antoon’s novel on the Iraq war, The Corpse Washer, the protagonist describes his job in this way:

If death is a postman, then I receive his letters every day. I am the one who opens carefully the bloodied and torn envelopes. I am the one who washes them, who removes the stamps of death and dries and perfumes them mumbling what I don’t entirely believe in. Then I wrap them carefully in white so they may reach their final reader – the grave.

The corpse washer, as a function of his occupation, attains a more direct, experiential perspective on war’s destruction than those who learn about it from the news. He sees and contemplates, over and over, the bodies, maimed, drained of life. His contemplation reveals not just the gunshot wounds, corpses, and destruction but also their particular awfulness. Such perception of dreadfulness forms the basis of further associations – it brings up related memories and images of violence. Attention to all this throws the dreadfulness of war into sharp relief.

Sensibility can be trained in many ways – art, music, mountain climbing, and even corpse-washing are ways to increase sensibility. It proceeds by joining contemplation with conceptual elaboration; the experience of an arpeggio is different for one who has the concept and for one who doesn’t; war’s ravages are different for someone who has the experience and vocabulary to grasp its gruesome details than for someone who doesn’t. The more attention one pays, and the greater conceptual sophistication one has, the more fine-grained one’s understanding of the world through experience and the more fine-grained one’s discernment of its values.

The corpse washer’s experiences lead him to grasp the war’s significance in ways that separate him from people who hear about it from the news or government briefings. Politicians use sanitized, abstract language, such as “civilian casualty” or “collateral damage,” while the corpse washer thinks about the various ways the body can be hurt, lives can be impacted by wounds, friends and family uprooted, etc.; all of which help him better understand what war is.

Appreciating the world

According to the Buddhist and Daoist tradition, contemplation fosters appreciation. The point is not just that contemplation discloses goods to pursue – it also leads to valuing life as such. It can bestow vividness and meaning on ordinary, boring, everyday activities; only it can create the sense that one’s life has touched the world. In Zen Buddhism, D.T. Suzuki remarks:

Life, as far as it is lived in concreto, is above concepts as well as images. To understand it we have to dive into and come in touch with it personally; to pick up or cut out a piece of it for inspection murders it; when you think you have got into the essence of it; it is no more, for it has ceased to live but lies immobile and all dried up.

In “Blacksmith Shop”, Czeslaw Milosz expresses the point vividly:

At the entrance, my bare feet on the dirt floor,

Here, gusts of heat; at my back, white clouds,

I stare and stare. It seems I was called for this:

To glorify things just because they are.

Slow decisions

…moral change and moral achievement are slow…the exercise of our freedom…is a small piecemeal business which goes on all the time and … not something that is switched off in between the occurrence of explicit moral choices. (Murdoch The Sovereignty of Good)

One might decide between career choices by weighing them in relatively abstract terms, such as the pay involved, the security the job offers, opportunities for learning, etc. Alternatively, one might frame the decision, at least in part, in terms of an assessment of what it might be like to work in those occupations. Such framing allows a more nuanced sense of the values involved as well as an authentic appreciation of them.

Objective deliberation, with its straightforward considerations of value and chance of success, is relatively fast. It doesn’t take weeks or months to complete. However, when value judgments are made in abstracto, they often have limited power to change behavior, as the fate of New Year’s resolutions shows. Contemplative deliberation, on the other hand, takes time. Though values are often perceived in experience, they are not always readily so – their discernment requires patience. In a slow decision process, one allows oneself to live with the question for a while, to dwell in experience long enough for one’s feelings about the decision to emerge. How one wants to spend one’s life and whom one wants to spend it with are discoveries rather than simply a matter of rationally appraising the known parameters of a situation.

Sometimes, even when all the relevant facts are known, it takes time to make a decision that feels appropriate. Such a decision can happen as a result of a familiar consideration presenting itself over and over again – as, for example, in the case of having to deal with an untrustworthy friend or lover. You might have understood, in an abstract sense, what is happening, and may have been at the point of trying to draw the consequences. But your decision never stuck, it never felt quite right. However, once you have gradually allowed yourself to experience your friend’s behavior fully – putting aside any effort to find excuses – you will likely come to a point where you can act. As Kierkegaard puts it in Either/Or,

Ask yourself, and continue to ask until you find the answer. For one may have known a thing many times and acknowledged it … and yet it is only by the deep inward movements, only by the indescribable emotions of the heart, that for the first time you are convinced that what you have known belongs to you … for only the truth that edifies is truth for you.

Contemplation and the contemporary world

As he died to make man holy

Let us die to make things cheap

(Leonard Cohen, “Steer your way”)

In the last few hundred years, since the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment – an interlude of romanticism notwithstanding, which brought back a passionate engagement with the sensuous aspect of our mental life – Western culture has changed in ways that provide less encouragement and space for any kind of sustained engagement with our experience.

Part of the reason is not specific to our age. Contemplation is difficult. It is often difficult to become aware of what we feel when many other things claim our attention. On top of that, it requires a certain amount of self-denial: it requires acceptance of the pain and joy that comes with experience, even if it doesn’t cast the self in the most flattering light. This runs against strong forces in human nature. One tries to escape pain whenever possible. Freud has cataloged the powerful built-in mechanisms that help expunge unwanted experiences from consciousness: repression, dissociation, sublimation, etc.

Even a small discomfort can prompt one to turn away from experience. If I pass a homeless person on the street, I might tune out so as not to feel any pangs of guilt for not having helped. As Iris Murdoch has observed, what needs to be learned is “how real things can be looked at and loved without being seized and used, without being appropriated into the greedy organism of the self.” Contemplation requires the skill to direct attention to what’s going on impartially, without distortion, which is perhaps most difficult when it comes to understanding and empathizing with others.

But our age seems particularly ill-suited to contemplation. We are getting lost in that hopeless little screen, as Leonard Cohen said. It is getting more and more difficult to find the silence, empty places, and the experience of being off the grid that we need to renew our connection to the world. Recent developments in AI also steer us away from contemplation. People think AI, even perhaps soon, will be able to do all the human things, only better, and so we are starting to think that we might not be so different from machines. Robots have become a new metaphor for ourselves. The four horsemen of technology, the internet, social media, AI, and virtual reality, push us away from ourselves and away from the world. But, while we might be forgetting how to contemplate and how to read, we are still the same humans. A future generation perhaps will rediscover what we are now losing.