by Mark Harvey

“Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” –HL Mencken

I’ve always loved Winston Churchill’s comment about his political rival Clement Attlee: “He’s a modest man, a lot for which to be modest.” Churchill himself was not a modest man, and when asked how he thought history would treat him, he responded, “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.” He did go on to write a significant historical tome titled The History of the English Speaking People and even won the Nobel Prize in literature for his writing and oratory. You could turn the phrase on its head to describe Churchill, the man who saw Hitler’s evil early on and helped lead the allies through World War II: he’s an arrogant bastard, and a lot for which to be arrogant.

America’s arrogance and individualism seem to be at a grotesque peak right now with our choice of president in the recent election. We’ve chosen perhaps the most arrogant man in history for a second term in the Oval Office. This is a man who compares himself to Lincoln and Washington, hinting that he might be greater than either one. Take a seat, Jesus Christ, your miracle work pales in comparison to his Eminence at Mar-a-Lago.

But it hasn’t always been so, and it’s good to remember those great American leaders who exhibited a healthy modesty, even those who had nothing to be modest about.

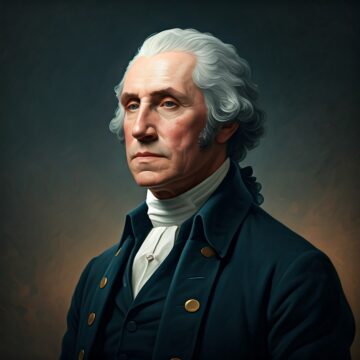

Our very first president, George Washington, though a snappy dresser, was modest to a fault. Upon being made commander of the Continental Army in 1775, he said, “I beg it may be remembered, by every gentleman in this room, that I this day declare, with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.” Washington was, of course, up to the task, probably more than any man alive at the time. Without his warring capacity, we might all be eating mince pies and Cornish pasties.

But he truly had little stomach for public appointments and certainly did not seek the presidency. After the long and bloody war fighting the British, Washington’s sole desire was to return to his wife, Mount Vernon, and his love of farming, or, as he put it, “to the shades of my own vine and fig tree.”

After the war, Washington had no desire to be president, but yielded to the will of those who insisted he take the office. In his inaugural address, he expressed his worry of his “incapacity as well as disinclination for the weighty and untried cares” before him. When Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, John Adams and others urged him to run for a third term, he refused. He thought it would set a bad precedent for the country as someone seeking absolute power.

During the revolutionary war, Washington rode a flashy white charger and would make a show of entering towns or cities. But from my reading, he did this as a show of strength to solicit the support of his countrymen and perhaps put fear into the British.

I’m coming to believe that most Americans vote on a vague sense of what a president can and can’t do for them, simple slogans, and a visceral attraction to a candidate’s personality. I doubt if many Americans parse policy positions or really consider what powers the executive branch has. Take gas prices, for instance. One of the most common complaints during the Biden administration was the high cost of gas early in his term when gas at the pump crossed the five-dollar mark.

You know who has very little control over gas prices: me and the president of the United States. You know who has significant control of gas prices: Abdulaziz bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s oil minister, and Alexander Novak, Russia’s oil minister. Yet I doubt if a single American filling up their F150 in 2022 bitched to their husband or wife, “Goddamn Abdulaziz, there he goes limiting crude oil production again. Gonna cost me more than a hundred bucks to fill my tank, thanks to that bastard.”

The same goes for food prices and the number of jobs created. There are things a president does that can affect both of these numbers, but the greater macro forces are much more consequential.

There are much better theories of how a president is chosen and many of them have to do with perceptions, the subconscious, and the zeitgeist at the time. In their book Implicit Leadership Theories: Essays and Explorations, Robert G. Lord and Ruth Kanfer argue that leaders are often chosen based on prototypes of what voters think a leader should look like. Furthermore, they say that people choose leaders based on mental shortcuts (schemas, or heuristics, to use a technical term). In choosing a candidate, it’s far easier to forego analyzing all of the complex issues of the times and make a choice based on a very simple impression or prototype of what a candidate represents.

I’ve watched too many of those silly “man-on-the-street” or vox populi interviews of why a person was going to choose Trump for president. The answers invariably include that “he’s a good businessman and he’ll run the country like a business.” The red tie, the boxy suit, and of course thirteen years on The Apprentice making great displays of firing people in a contrived boardroom offer a very nice heuristic for “good businessman.” But anyone with even a faint interest in his business accomplishments would realize that he managed to go through four bankruptcies in his New Jersey casinos alone. Somehow the failed Trump steaks, vodka, airlines, and university barely made a dent in his persona as shrewd businessman.

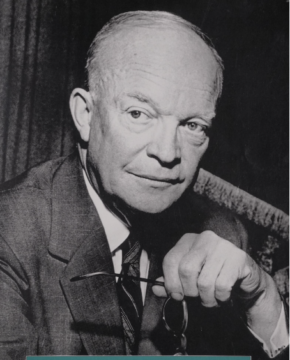

Another of our great generals, Dwight Eisenhower exhibited some of the same unassuming characteristics as Washington. Eisenhower grew up in the dusty cattle town of Abilene, Kansas. His journey to become Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces and saving Europe from the Nazis was unlikely, but he seemed to have remembered his modest beginnings.

Counseling Louis Mountbatten, the allied commander in southeast Asia during World War II, on how to be a good leader, Eisenhower wrote,

He must be self-effacing, quick to give credit, ready to meet the other fellow more than half way, must seek and absorb advice…take full blame for anything that goes wrong; in fact he must be quick to take the blame for anything that goes wrong whether or not it results from his mistake or from an error on the part of a subordinate.

That philosophy in today’s America might be construed as weak even though Eisenhower oversaw the greatest war effort in human history. He was revered worldwide and even before WW II ended, he was awarded Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire by the King of England. It’s easy to imagine him being smeared in today’s scummy political climate and even being cast as a communist. For Eisenhower supported the right to unionize and said, “Only a fool would try to deprive working men and women of their right to join the union of their choice.” He also prevented men from his own party from dismantling Social Security.

The heuristic or schema of Eisenhower would be that of the quiet warrior, unsung hero, or silent sentinel. In other words, with today’s lust for self-aggrandizement, he wouldn’t stand a chance of being elected. As an aside, Eisenhower was running against a thoroughly decent, accomplished man named Adlai Stevenson, then Governor of Illinois. So in 1951, Americans had the delicious choice between the man who lead the Allies to victory or a more liberal but highly competent and articulate governor. My how poor we’ve become.

Even if the president doesn’t control the price of gas and is often at the mercy of macro-economic forces, he does have a huge influence on the country’s morality and character. How a president comports himself bleeds into the national fiber. Trump’s refusal to accept the results of the 2020 election begat Kari Lake’s refusal to accept her own defeat in the Arizona gubernatorial election, and Eric Hovde’s refusal to admit defeat in Wisconsin against Senator Tammy Baldwin. All of Trump’s endless whinging and whining has created a whole class of American cry babies who just can’t take responsibility for their personal failings.

The contrast to some of our forebears is almost too painful to consider. Take D-Day for example. You’ll recall from your high school history that D-Day was one of the riskiest and also most consequential military operations ever conceived. It involved an amphibious assault with more than 150,000 men landing on five beaches in Normandy. The initial plan had the troops landing on June 5, 1944, but the weather that day was terrible, and the assault had to be postponed. So that left it to Eisenhower, who had sole control of the operation, to decide on whether or not to proceed the following day, when the seas were still quite rough. He chose to attack, but just hours before the allied assault, he wrote a note accepting full blame in case the attack failed. The note read in part,

Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. The troops, the air, and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.

He carried the note in his pocket that memorable day, ready to read it publicly had there been a failure.

President Roosevelt wanted to award Eisenhower the Medal of Honor during the war, but Eisenhower turned him down. He said it was awarded for valor and he hadn’t done anything “valorous.” Given today’s blowhards running for office, that act of modesty seems almost fictional.

Americans who didn’t vote for Trump wonder how a convicted felon, a sexual predator, and a man who often stiffed small contractors working on his buildings could enter the same Oval Office once held by Washington, Eisenhower, and someone nicknamed Honest Abe. Implicit Leadership Theory says that disillusioned voters sometimes find a scoundrel attractive. A rule breaker might help break down the institutions some citizen have come to revile. In times of crisis or fear, voters find the authoritative “strongman” appealing even if he has virtually no morals.

But this is where I abandon Implicit Leadership Theory. It’s one thing to be unhappy with your lot in life, your country, and the way things are headed. And millions of Americans are truly struggling in a country with huge disparities of income. But it’s altogether irresponsible to vote for someone who is going to make your life worse just because he has the cheap facade of a businessman. Whether you have preexisting medical conditions, trouble paying for groceries, a daughter who may someday have a septic pregnancy, or a concern with that most existential threat––climate change––the policies espoused by Trump and his proposed cabinet will make your life sadder and sorrier.

During one of Adlai Stevenson’s campaigns, a woman yelled, “Every thinking person will be voting for you!” Perhaps prophesying today’s America, Stevenson replied, “That’s not enough, madam, we need a majority.”