Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

If Harold Bloom is correct in asserting that, in some sense, Shakespeare invented the human, not in the sense that Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, Alexander Graham Bell the telephone, Thomas Edison the light bulb, Hedy Lamar got a patent for frequency-hopping spread spectrum technology, not to mention Yahweh’s work on Adam and Eve, but in the modest sense that he bequeathed us a deeper understanding of ourselves through giving voice to aspects of human behavior that had hitherto gone unremarked. Bloom singles out Hamlet for special consideration, arguing that he is perhaps Shakespeare’s greatest gift – though Falstaff is in the running. Hamlet has come down to us as the melancholy Dane. Accordingly, let us conjecture that modern man was born in melancholy.

A few years later Robert Burton would publish The Anatomy of Melancholy. It was a smash hit and went through five more editions during Burton’s life. It made Burton’s printer a fortune. While the book is indeed about melancholy, it is also about damned near everything else under the sun. It was subsequently parodied in Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, no mean feat as the original has something of a parodic character unto itself.

Here is how Burton defined melancholy:

Melancholy, the subject of our present discourse, is either in disposition or habit. In disposition, is that transitory melancholy which goes and comes upon every small occasion of sorrow, need, sickness, trouble, fear, grief, passion, or perturbation of the mind, any manner of care, discontent, or thought, which causeth anguish, dullness, heaviness and vexation of spirit, any ways opposite to pleasure, mirth, joy, delight, causing frowardness in us, or a dislike. In which equivocal and improper sense, we call him melancholy that is dull, sad, sour, lumpish, ill disposed, solitary, any way moved, or displeased. And from these melancholy dispositions, no man living is free, no stoic, none so wise, none so happy, none so patient, so generous, so godly, so divine, that can vindicate himself; so well composed, but more or less, some time or other he feels the smart of it. Melancholy in this sense is the character of mortality.

To live is to know melancholy. We post-moderns are more likely to call it depression.

That’s what this post is about, depression, but also growth.

And while I will have something to say about the general case – I hear that depression is on the rise, especially since the pandemic – I’m going to start with the depression I know best: mine. I’ve known it my entire adult life, for months at a time. It’s never been to the point where I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning or couldn’t eat. I’ve never lost weight over it. And, yes, I’ve had thoughts of suicide, but only thoughts. I’ve never gotten near making an attempt, much less attempting and failing.

While I’d hardly call melancholy a friend, it’s no stranger either. I know it well. It may be a manifestation of personal growth.

That’s what this is about: First, I discuss my mood as indicated by two charts depicting my blogging habits. Second, I discuss the possible relationship between depression and mental growth, availing myself of a discussion with Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Sonnet. If I believe, as I do, that there is a relationship between depression and creativity, then I should present evidence, no? I do that in the third section, developing a way of measuring my mental growth by counting the tags (category labels) I use for posts at New Savanna. I conclude with two sections arguing for new kinds of mindcraft, ways of crafting minds to thrive in the emerging world of A.I.

Reading Tip: The reasoning in the first and third sections is not particularly abstract and difficult, but you may find it a bit tedious. If so, you might want to skim through it and skip to the last two sections, though not after you’ve read about depression and creativity.

My Posting Habits Over the Last Decade

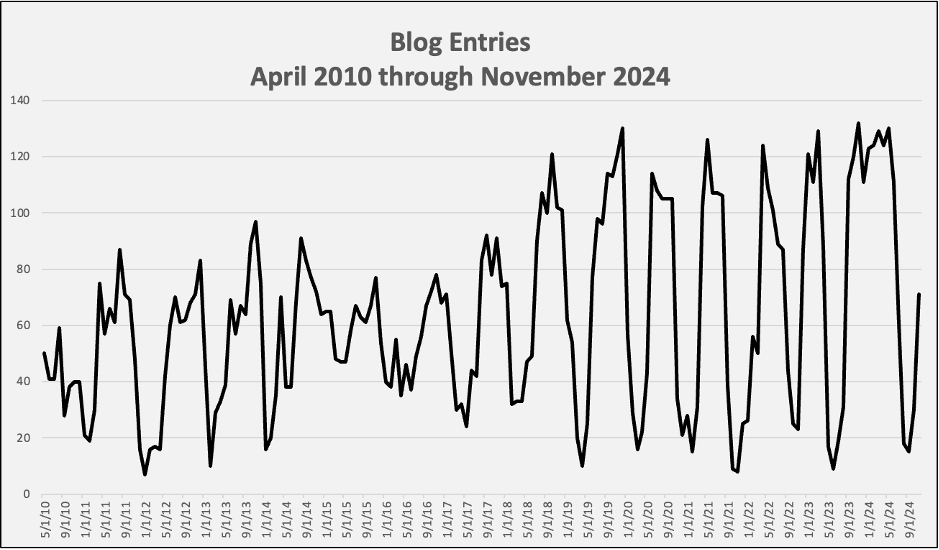

I started blogging at The Valve, a now defunct group blog, early in 2006. I created my personal blog, New Savanna, in April of 2010. The blogging platform I use (Google’s Blogger) maintains a list of posts arranged by year and by month. Roughly speaking, my posting frequency is inversely proportional to my mood: When I’m in good spirits I post a lot; when I’m depressed, posting goes down (and I spend a lot of time streaming video online).

Over the life of New Savanna there has been four months where I made fewer than four posts, with January 2012 being the lowest, 7 posts. In contrast, I’ve done over 100 posts a month from September 2023 through June 2024, a 10-month run. The following chart depicts my blogging activity over the life of the blog, ending in October of this year. I take this chart as a crude measure of my mood over the last decade or so.

The most obvious feature of the chart is that it is very spikey. As I have already indicated, my monthly posting frequency varies widely. That variation seems to be fairly regular; the low months tend to occur during the winter – something we’ll return to in a minute.

There are two secondary features of the posting pattern. The overall frequency seems to be higher since about 2018 and there is a five-year stretch from March 2014 through February 2019 where there the “floor” of the posting frequency is higher than it is in any other region of the pattern. Those features, however, do not obliterate dominant quasi-periodic pattern of posting frequency, so I’ve decided to discuss them in Appendix 1.

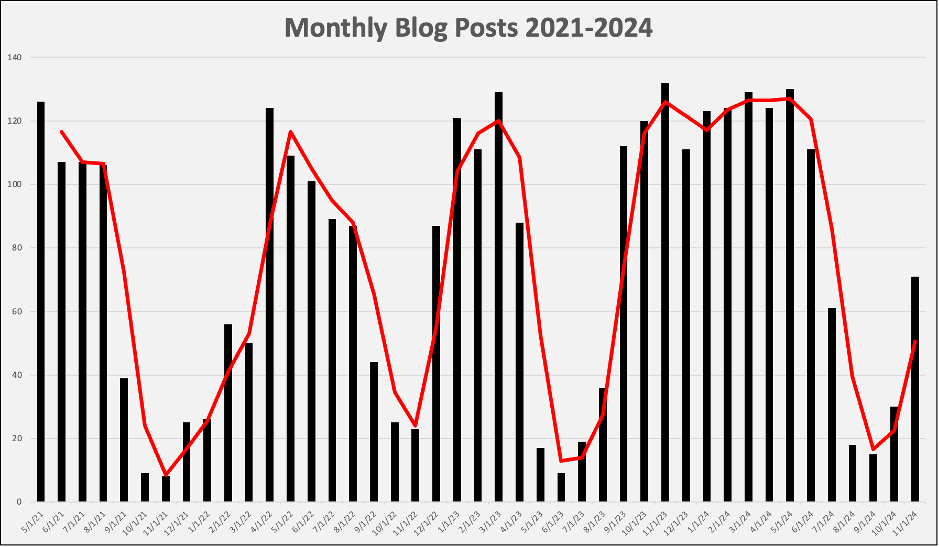

That leaves us with the period from May of 2021 to the present, where the SAD pattern is contradicted. Let’s take a closer look:

I’m interested in this period because it deviates from the winter slump pattern – a pattern that’s been with me most of my adult life, not just since I’ve started blogging. Some years ago a friend suggested that I was prone to Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD), a well-known phenomenon in which one is prone to mood slumps during the Fall and Winter. The cause is not well understood, but a decrease in sunlight leading to a drop in vitamin D may be one factor. The drop in vitamin D in turn leads to a drop in serotonin levels.

What does the data say? Starting from the left, I made over 120 posts in May 2021. Then I dropped below 40 in September, below 10 in November and December, and then rose above 120 by May 2022. The winter of 2022-2023 had its nadir of 23 in November of 2023. But then we’re up to 87 posts in December and over 100 for January, February, and March of 2023. I’m blogging like crazy. What’s up?

What’s up is ChatGPT. It was released at the end of November 2022 and I started playing with it immediately. I made my first ChatGPT post on December 3. I asked ChatGPT to interpret a Jerry Seinfeld bit. On December 5 I posted a 3 Quarks article reporting how ChatGPT used the ideas of René Girard to interpret Spielberg’s Jaws.

What’s up is ChatGPT. It was released at the end of November 2022 and I started playing with it immediately. I made my first ChatGPT post on December 3. I asked ChatGPT to interpret a Jerry Seinfeld bit. On December 5 I posted a 3 Quarks article reporting how ChatGPT used the ideas of René Girard to interpret Spielberg’s Jaws.

I was on fire! In the dead of winter.

I spent a lot of time playing with ChatGPT. Yes, playing, having fun, because that’s how these things go. There’s work too, especially in the writing, of which I did a lot. 121 posts for January, 111 February, and 129, March.

What happened to SAD? I’m supposed to be down in the dead of Winter, not up. Is something else going on?

I think so, but let’s continue looking through the data. My posting frequency drops in April 2023, to 88, continuing to 17, 9, 19, and 36 for May through August. That’s not the SAD pattern either.

It looks like the creativity ran out. Moreover, creativity is one thing. Creativity is intrinsically rewarding. But there’s also recognition, and creativity doesn’t always attract recognition. It’s not as though I was expecting my ChatGPT work (reported in my New Savanna blog, but also 3QD) to attract wider recognition, but I was hoping – one can always hope, no? More specifically, I sent work – good work, exciting work to specific people – and got no response. Nor is it the mere fact of recognition I desire. Recognition would get me into the larger conversation where the ideas would have a chance to speak for themselves.

Rats!

Then, into Fall and heading into Winter, I had 112 posts in September and the number stayed above 100 through June of this year. What happened? I found collaborator, Ramesh Visvanathan, an expert in machine vision at Goethe University, Frankfurt. And not just any collaborator. Visvanathan has technical expertise in mathematics that I lack.

Over the years I’ve developed sophisticated mathematical intuitions, but I lack technical skill. For the first twenty years of my career I had David Hays to keep me honest. He was one of the founders of computational linguistics and was my teacher in graduate school. Later on there was my friend Tim Perper, who was trained as geneticist and used chaos theory to examine the dynamics of courtship (see some of his mathematical advice in this paper on self-organization). Tim introduced me to the work of and the late Walter Freeman, an expert in complex neurodynamics. I contacted Freeman and we had extensive correspondence during the first decade of this century. Since Tim Perper died I had been without mathematical advice and counsel. That’s recently changed. Ramesh and I have been emailing and Zooming for a bit over a year now and we had an intense two-day in-person session when he came to America on business last winter. Things look good for the future.

You may have noticed, if you’ve been paying attention to the details, that my posting frequency took a dip starting in August. But it started going back up in October. I suspect it will remain high in December – I certainly hope it will – but who knows?

That dip needs to be explained. But it has to be brief as I’m anxious to move on with this essay. In short, failed expectations: my work on ChatGPT was beginning to get repetitious, and there’s that pesky recognition thing.

These things aren’t simple. The fact is, though, that seasonal affective disorder is not sufficient to explain the long-term fluctuations in my posting pattern. Something else must be going on. I think that something else is creativity itself. Creativity is not simple and it is not constant.

Let’s take a look.

Depression and Mental Growth

First, consider this passage from an article Joanna Thompson published in Quanta in 2023:

Increasingly, some scientists are pushing to reframe “depression” as an umbrella term for a suite of related conditions, much as oncologists now think of “cancer” as referring to a legion of distinct but similar malignancies. And just as each cancer needs to be prevented or treated in ways relevant to its origin, treatments for depression may need to be tailored to the individual.

If there are different types of depression, they may present similar symptoms — such as fatigue, apathy, appetite changes, suicidal thoughts, and insomnia or oversleeping — but they might emerge from completely different mixes of environmental and biological factors. Chemical imbalances, genes, brain structure and inflammation could all play a role to varying degrees.

Now consider this statement from the abstract of a recent article by Seven Hollon: “In brief, depression is far more prevalent than previously recognized with the bulk of additional cases involving individuals who do not go on to become recurrent. Nonpsychotic unipolar depression (but not bipolar mania which likely is a “true” disease) appears to be an adaptation that evolved to facilitate rumination in the service of resolving complex social problems in our ancestral past.” Depression can be adaptive. I like that.

That’s a view I’ve held since my years in graduate school studying with David Hays, who was prone to spells of melancholy. He speculated that it was something like mental hibernation, where the mind withdraws from the world so that it can reorganize internal structures.

I decided to put the question to Claude, Anthropic’s chatbot. Now, let’s be clear, I do not believe that Claude is thinking in any deep sense. I don’t know what it’s doing; neither does anyone else. But it has absorbed a much wider range of material than I have, much, and that makes it useful. Moreover, as this article as largely speculative, why not give Claude a whirl? There are some core facts, about my blogging activity, but the rest is speculation. I’m thinking out loud. I’m having fun.

So, I began by asking Claude: “Is there any evidence for a relationship between depression and creativity?” It gave a general answer to which I replied by mentioning Hays. [You can find the complete interation here.] Then things got interesting (my words are set in bold):

I think Hays primarily developed the idea [depression as mental hibernation] from observing his own creative process. But he might also have been thinking about computers. Your remark about reorganizing data structures is suggestive. I know one thing that programmers do is refactor their code. That’s a specific kind of reorganization so it is more coherently organized.

The parallel between mental reorganization and code refactoring is quite illuminating. In refactoring, you don’t change what the code does (its external behavior), but you restructure its internal organization to make it clearer, more efficient, or more maintainable. This often involves recognizing patterns that weren’t obvious in the original implementation and finding a better way to express them.

This maps interestingly onto Hays’s idea about depression and creativity. Just as a programmer might hit a point where the code has become too unwieldy and needs refactoring, a person might reach a point where their current mental models or ways of thinking have become inadequate for handling their experiences or insights. The depressive period could be like the uncomfortable but necessary process of pulling apart the existing structure to create something more robust. […]

Did Hays discuss what might trigger these periods of necessary reorganization? I’m wondering if there are particular types of cognitive challenges or experiences that tend to precipitate this process.

Or think of an evolutionary process, where the species hits an evolutionary dead end. So it’s got to dedifferentiate and try again. Arthur Koestler used a French phrase to talk about this: “reculer pour mieux sauter.”

That’s a brilliant connection! “Reculer pour mieux sauter” – step back to better jump forward – captures this idea perfectly. The evolutionary parallel really illuminates both Hays’s theory about depression and the whole concept of creative restructuring.

n evolution, when a species hits a dead end, it can’t just make small incremental changes anymore – it needs a more fundamental reorganization. Some evolutionary biologists talk about “despecialization” where organisms lose specialized features before developing new ones. This is similar to how stem cells need to dedifferentiate (become less specialized) before they can develop into new cell types. […]

The French phrase really captures the intentionality or purposefulness of this retreat – it’s not just stepping back, but stepping back specifically to gather force for a better leap forward.

It also relates to current work in machine learning and neural networks where an evolutionary style of computing is involved.

Yes! This connection to machine learning is really insightful. In artificial neural networks, there are several phenomena that mirror this “step back to leap forward” pattern:

- In gradient descent optimization, sometimes the system needs to move “uphill” temporarily (accepting worse performance) to escape a local minimum and find a better global solution. This is why techniques like simulated annealing deliberately introduce random noise or “temperature” to help the system explore more widely.

- In training neural networks, processes like “dropout” temporarily deactivate some neurons during training. This forced dedifferentiation helps prevent overfitting and leads to more robust learning – similar to how depression might force a “dropping out” of established mental patterns.

- In evolutionary algorithms and genetic programming, the concept of “reversion” or returning to less specialized states is built into operations like mutation and crossover. The system sometimes needs to break down existing solutions to explore new evolutionary pathways.

It’s fascinating how these computational processes mirror biological evolution, creative thinking, and potentially the depression-creativity cycle Hays described. All seem to involve periods where existing structures or patterns need to be destabilized or broken down to enable new forms of organization to emerge.

Bingo! Tilt! Shazaam! “We’re cooking with gas,” as my aunt Bell used to say.

Could we actually learn something about the human mind by examining and analyzing the behavior of machine learning systems? I think so. To be sure, that’s not what the Silicon Valley spin masters are hyperventilating about, but there are neuroscientists who are working on it. In the long run – five, ten, or more years – that may prove as important for progress in A.I. as mega-clusters of GPU-machines powered by Niagara Falls. When it comes time for A.I. to step back to better jump forward, the neuroscientists will be there along with Gary Marcus and his symbol masters, and who knows who else.

Let’s move on.

Measuring My Mental Growth

Having suggested the depression is adaptive, that it is a means to intellectual growth, can I offer any evidence in my case? Well, no, not really. It’s tricky. But I’m willing to argue that I have experienced intellectual growth over the life of my blog, but I’m not going to try to argue that my periods of depression have had a causal role in that growth, though I do believe it to be so.

To make my argument I have to present some definition of mental growth along with a way of measuring it. If I can’t somehow measure that growth, then there’s no way to make my argument, is there? Keeping in mind that I’m pretty much making this up as we go along, I’m going to develop the two things, the definition and the measure, in parallel.

Let’s start with a simple suggestion: number of blog posts. Since my blogging platform (Google’s Blogger) counts the number of posts I make each month, that’s similar. The charts I’ve already presented show those numbers. This is similar to perhaps the central way the academic world measures the research productivity of scholars. You count the number of articles you’ve published, grants you’ve snagged, presentations you’ve given, and so forth. But that isn’t necessarily evidence of growth. Any savvy academic will tell you that the cheap way to tenure is to publish the same idea five times a year for five or six years. That’s productivity, but it hardly seems like growth. If we’re going to talk of growth, we’d like to see evidence that something new is happening. Simply counting blog posts is out.

I suggest, instead, that we look at tag count. Every time I post an item, I have the option of tagging it with one of labels indicating something about the post. As of November 22 of this year I have used 746 different tags. On August 23, 2011 I had 308 different tags. That’s the earliest count I have. Let’s divide that current November count by the age of the blog in years (14.9). We get 51.

So, my mind has grown at the rate of 51 tags per year for the last decade and a half. That seems a bit silly on the face of it. Minds don’t have tags! But let’s hang in there.

It’s not the tag itself that interests me. I’m taking the tag as an indicator of mental activity of some kind. For example, I’m interested in philosophy, science, literature, psychology, AI, and pop culture. All of those are tags. Any post that’s on one of those subjects will be given the relevant tag. Those are broad categories. But I’ve got tags for narrower categories as well: 3300 node graph, Alan Liu, bardolatry, comfort, description, hyperobjects, King Kong, Miyazaki, nation-state, and on and on through the whole alphabet for a total of 746 tags and counting – I’ve attached a complete list (Appendix 3).

Where did all those tags come from? Tags are like entries in the index of a book, they index the contents of the blog. They provide the reader with a way of finding things. As the blog developed, I started using tags as a way to refer directly from one post to a group of other posts. There’s where they come from.

And I’m the primary reader of New Savanna. If you’ve spent much time in the blogosphere – which isn’t what it was before the advent of so-called social media – you know that many, perhaps even most, but not all blogs have a tag list somewhere (3QD doesn’t have one). When you click on a tag, the blog displays all the posts having that tag. The tags will be attached to the end of each post as well.

I add tags to the list when, and only when, I want a convenient way to refer to a set of blog posts. Let’s say I write a post about a film by Hayao Miyazaki. I might tag it with “anime,” “film,” and “Japan.” A couple days later I’ll write another Miyazaki post; same three tags. But I also insert a link to the previous Miyazaki post because I refer to it. Before long I’ve written another Miyazaki post, another, and yet another. In each case I want to refer the reader to the other Miyazaki posts. Creating explicit references to the other posts gets to be tedious when its four, five, and six or more posts. We can eliminate that problem by adding a new tag. Now when I write another post about Miyazaki – or anime, Japan, pop culture, air planes, whatever – and want to refer the reading to my Miyazaki posts, I simply put a “Miyazaki” link at an appropriate place in the post itself and the job is done. I don’t have to add specific references to each other Miyazaki post. Tags are thus a way to make specific references between posts (like writing page number references in the margins of a book, which I do all the time).

When you do that for almost 15 years, you get a lot of tags. While a few tags are quite general and thus link to many posts, most of them are more restricted, some quite restricted. I’ve chosen them with care. The growth of the tag list thus tracks the evolution of my interests over year.

I suggest, then, that we use tag counts as a way to measure mental growth. That is, since I have no way of directly observing my mind – thinking about it is not observing it – I’m going to use those tags as a proxy measure, which is a common practice in the social sciences.

Now saying that my mind has grown at the rate of 51 tags per year doesn’t seem so silly. I may be a bit odd, but it is real. The relationship between those tags and the contents of my blog is straight-forward and transparent. Those blog posts are expressions of my mind, and those tags index the contents of those posts, making them a proxy index for the contents of my mind.

While we’re playing around, let’s push this another step further. Instead of expressing growth in terms of new-tags per year, let’s express it as a percentage increase. I had 308 tags in August, 2011 and 350 in August, 2012, for a 14% increase. Similarly: November 2023, 655 tags, November 2024, 746 tags, for a 14% increase. Unfortunately those are the only cases where I’ve got tag counts for successive years.

However, it’s easy enough to pose a question: If we have 308 tags in one year, and 746 tags 13 years later, what annual percentage rate will get us from the first count to the second? There’s probably a direct way of calculating the answer, but I don’t know what it is. That is a compound interest problem and the internet has plenty of sites that will calculate compound interest (so will my Excel spreadsheet, but I don’t know how to do that). The fact that I’m compounding tags rather than dollars is irrelevant. So, I went to one of those sites, did a little playing around, and discovered that 308 tags compounded annually at 7% is 742 tags, which is pretty close to 746.

That’s quite different from the two cases where I found a 14% increase. From that I conclude that the percentage varies from year to year, often considerably. I can’t say that I find that surprising. But what does that actually mean? It’s not like I have anything to compare these numbers with. As I said when I began this process, I’m just making this up, playing around. I do a lot of that, especially in up “UP” months. That’s how a lot of these blog posts have gotten written.

Let’s play around just a little bit more. I want to treat that percentage as a measure of differentiation. In fact, that’s why I decided come up with a measure that can be expressed as a percentage. Remember, I’m using these blog tags as a proxy for my mind. What’s a mind consist of? Thoughts, ideas, feelings, desires? Sure, and all of those things are vague. I don’t know how to count and measure them. Nor do I really understand how these specific tags relate to countable things in/about my mind. But I can eliminate, or at least lessen, that problem by converting these numbers into percentages. I am happy to think of the mind as something that has internal structure and I’m happy to imagine that that structure differentiates over time, or, for that matter, that structure dissolves. It makes no sense to say that my mind differentiated by had 91 tags of differentiation between 2023 and 2024 (655 to 746). But saying that its internal structure experienced a 14% increase in differentiation, that makes (more) sense. I now longer care just what those tags indicate. All I care about is that there’s more of them.

I could say more – I’ve got more unexpressed thoughts on this matter still swirling around in my brain – but, really, this is enough. You get the idea. Rather, if you DO get the idea, you can imagine additions, qualifications, corrections, and embellishments of your own. But if this still seems like arrant nonsense, well, there’s nothing more I can do at this point beyond pointing out, once again: 1) The New Savanna blog is real; you can read it whenever wish want to. 2) Those tags are real and their relationship to those posts in that blog is transparent. The blog and the tags are certainly expressions of something, my mind – but, when you examine the blog, your mind engages the process. Something’s going on, and we need to figure out how to talk about it.

Some More General Observations: Mind and Brain

It’s been a long way through this article, about 4500 words to this point. Where do we stand?

That’s tricky because this is mostly about one person, me. Is there anyway to generalize from what I’ve done?

While the two charts I presented at the beginning are in fact about my blogging behavior, I spend so much time blogging and blogging is so central to my life that the charts also an important aspect of my medical history. Over the past couple of years I’ve visited medical professionals who have taken my medical history. I would tell them about my depression. Those charts present that history more clearly than my words did. They should be included in my medical records.

I have no idea how many people work with computers in a way that their activity leaves a clear and accessible trace of their long-term moods like my blogging does. Blogging is not as widespread as it once was, and I doubt that most bloggers do so as regularly as I do. But blogging isn’t the only thing people do with computers. What information about long-term-moods is latent on people’s computers? What would it take to recover and present that information? If we knew what to look for, could a computer’s operating system be designed to automatically track that information?

Various wearable biosensors have been developed in recent years to monitor a variety of physical variables continuously throughout the day and are being used healthcare monitoring and disease management. What about tracking state of mind, which is how I am treating data about my blogging activity? I have no idea what would be possible. But with the recent emergence and flourishing of A.I. technology, surely there is work to be done in this arena.

Let me further observe that, whatever the idiosyncrasies of my story, as far as I know, there’s nothing idiosyncratic about my brain and nervous system. With that in mind, let us note that most of the brain’s physical development takes place up through adolescence, but some physical maturation continues into the 20s. Our society has organized our educational and occupational systems to fit this pattern. We concentrate education in the early years, when the brain is most open to influence and molding. When one’s education is complete, you enter the workforce. The underlying assumption is that, once education is complete, one’s mental architecture and capabilities are set for life. You can add on to that or modify it as needed for work, but nothing fundamental needs to be done.

I have in effect been suggesting that my pattern of periodic depression is a symptom of a life-long need to restructure my brain, certainly not top-to-bottom, but enough. That need is a function of life-long curiosity that forces/leads me to new intellectual activities. We’re living in a world where the pace of changes is forcing more and more people to restructure whether they like it or not.

Almost everyone receives a high school education early in life, the period of maximum neural flexibility. In the United States the majority of the population completes their education at that time and enters the workforce. The rest go on to get a bachelor’s degree or even an advanced degree before they enter the workforce.

I got a doctorate (in literary studies) and have been learning new things my entire adult life, not just adding on to what I’d already learned, and not just learning it, but synthesizing it and publishing those ideas. That, I speculate, is at least one of the factors driving the boom/bust cycle of my posting habits. Yes, there may be an element of seasonal affective disorder (SAD), but there’s also the psychic labor required by periodic neural reorganization and retooling.

For the last few decades, as we’ve noted, we have been moving into a world where more and more people have to undergo mental retooling during adulthood. This process is going to spread and accelerate with the emergence of A.I. Many existing jobs will disappear, others will be restricted in ways that seem strange, at least initially, and new jobs will emerge. It will not be easy.

Is it really too much to suggest that more and more people are facing the need for similar periodic neural reorganization and retooling? How will that affect the long-term patterns of their moods? How has that already been affecting people?

Let me give a particular and somewhat surprising example, the emergence of retirement coaches. A decade ago The New York Times had an article about them:

When Guy Johnson retired from his tax management position at Unilever, one of the world’s largest consumer products companies, he was sure that he was prepared. But he was fooling himself.

“I lost myself when my wife, Barbara, and I moved to Sarasota, Fla., from Bergen County, N.J.,” Mr. Johnson said. “I planned my retirement financially, but I didn’t plan it otherwise.”

This summer, through weekly sessions with a retirement coach, Debbie Drinkard Grovum, the 68-year-old is working hard “to accomplish the goals in life that I’ve been putting off since I retired 10 years ago. She keeps me motivated.”

Retirement coaches like Ms. Grovum are popular these days. The cadre has emerged in the crowded coaching field to cater to a growing number of boomers who are grappling with what’s next.

A life-time of hard work has conditioned people to develop the habits of mind required to work their job. Many have become over-conditioned. When those habits of mind were no longer needed, they were unable simply to switch into other mental modes. That requires reworking neural pathways throughout the brain, the process of stepping back to better jump forward that I mentioned above.

I saw this in my father. He took early retirement at 62, and then, once he retired he started playing solitaire, hour after hour, day by day. He had many interests, and eventually the solitaire tapered off and he spent more time pursuing those interests. But it took time, years.

Conclusion: Crafting Minds

If we are to navigate the future, we are going to need to develop new forms of mindcraft. Mindcraft, the crafting of minds. Reading, writing, and arithmetic are forms of mindcraft. So are the many meditation disciplines. The many forms of psychotherapy are forms of mindcraft as well, as is life coaching.

More than any previous technologies, computation is a mind technology. The tasks that computers do are tasks that had previously been done only by minds, human minds. During the early decades only a small group of people had to craft their minds for computer interaction. With the advent of personal computers more people could interact with computers, but most of us have interacted with them in only a superficial way. The recent, very recent, emergence of machine learning into the public sphere is bringing many more of us into deeper interaction with computers, interactions we don’t understand. Will these machines craft our minds as we craft them?

The question of whether or not these devices themselves have minds is a real one. For what it’s worth, I don’t believe any of these devices yet have minds. But I don’t rule it out.

That’s the future, how distant, I don’t know. My immediate concern is less conjectural: Recalling Claude’s remarks about reorganizing processes in computers, what can we learn about our own minds by studying A.I. devices? More practically, how can we learn more about our own (individual) minds by tracking patterns of computer usage? How can we use those patterns to understand ourselves and to better manage our own lives. That is the mindcrafting facing us now.

Appendix 1: Secondary features of my posting pattern

In the body of the essay that there were two secondary features of my posting pattern that I wanted to set aside for the moment: 1) an increase in frequency after about 2018 and 2) a five-year stretch where the “floor” is elevated above 20 posts per month.

Let’s look at the first. On September 4, 2018 I made the first post containing a tweet, a practice I’ve continued, though I suppose we shouldn’t call them tweets anymore. Tweet posts are simple to do; they require little psychic energy. That seems to account for that increase, though ease of posting doesn’t seem to have raised the floor on my low periods.

What’s going on roughly during a five-year stretch from March 2014 through February 2019? There are no months were the frequency drops below 20 per month; and it doesn’t drop below 35 through January 2018. I note, however, I was spending a fair amount of time during that period with my friend Greg Edgell, who curated graffiti murals throughout Jersey City, photographing the murals. During the summer of 2015 Greg curated a major exhibition in a Pep Boys building that was scheduled for exhibition at the end of the summer – The Demolition Exhibition. That activity had me out and about more than usual. That may have helped to keep my mood up.

Appendix 2: 3QD Posts about computers and culture

I have written a number of 3QD articles about the intersection of computers and the mind. Here’s a list, in order from the earliest to the most recent:

- Some notes on computers, AI, and the mind

- An Electric Conversation with Hollis Robbins on the Black Sonnet Tradition, Progress, and AI, with Guest Appearances by Marcus Christian and GPT-3

- To Understand the Mind We Must Build One, A Review of Models of the Mind – Bye Bye René, Hello Giambattista

- Welcome to the Fourth Arena – The World is Gifted

- On the Cult of AI Doom

- Conversing with ChatGPT about Jaws, Mimetic Desire, and Sacrifice

- ChatGPT is a miracle of rare device. Here’s how I’m thinking about it.

- From “Kubla Khan” through GPT and beyond

- World, Mind, Learnability, Large Language Models, and the Metaphysical Structure of the Cosmos

- Beyond artificial intelligence?

- Mind Hacks R Us: The Psychedelic Computer

- Aye Aye, Cap’n! Investing in AI is like buying shares in a whaling voyage captained by a man who knows all about ships and little about whales.

- Western Metaphysics is Imploding. Will We Raise a Phoenix from The Ashes? [Catalytic AI]

- Thirteen Ways To Think About An A.I.

Appendix 3: New Savanna tags as of December 1, 2024

Here they are, all of them. You’re looking at a crude map of my mind, low resolution and incomplete. Click on a link: Welcome!

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.