by Ashutosh Jogalekar

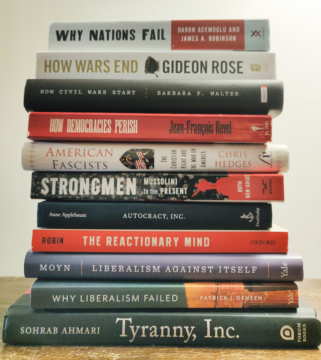

In October last year, Charles Oppenheimer and I wrote a piece for Fast Company arguing that the only way to prevent an AI arms race is to open up the system. Drawing on a revolutionary early Cold War proposal for containing the spread of nuclear weapons, the Acheson-Lilienthal report, we argued that the foundational reason why security cannot be obtained through secrecy is because science and technology claim no real “secrets” that cannot be discovered if smart scientists and technologists are given enough time to find them. That was certainly the case with the atomic bomb. Even as American politicians and generals boasted that the United States would maintain nuclear supremacy for decades, perhaps forever, Russia responded with its first nuclear weapon merely four years after the end of World War II. Other countries like the United Kingdom, China and France soon followed. The myth of secrecy was shattered.

In October last year, Charles Oppenheimer and I wrote a piece for Fast Company arguing that the only way to prevent an AI arms race is to open up the system. Drawing on a revolutionary early Cold War proposal for containing the spread of nuclear weapons, the Acheson-Lilienthal report, we argued that the foundational reason why security cannot be obtained through secrecy is because science and technology claim no real “secrets” that cannot be discovered if smart scientists and technologists are given enough time to find them. That was certainly the case with the atomic bomb. Even as American politicians and generals boasted that the United States would maintain nuclear supremacy for decades, perhaps forever, Russia responded with its first nuclear weapon merely four years after the end of World War II. Other countries like the United Kingdom, China and France soon followed. The myth of secrecy was shattered.

As if on cue after our article was written, in December 2024, a new large-language model (LLM) named DeepSeek v3 came out of China. DeepSeek v3 is a completely homegrown model built by a homegrown Chinese entrepreneur who was educated in China (that last point, while minor, is not unimportant: China’s best increasingly no longer are required to leave their homeland to excel). The model turned heads immediately because it was competitive with GPT-4 from OpenAI which many consider the state-of-the-art in pioneering LLM models. In fact, DeepSeek v3 is far beyond competitive in terms of critical parameters: GPT-4 used about 1 trillion training parameters, DeepSeek v3 used 671 billion; GPT-4 had 1 trillion tokens, DeepSeek v3 used almost 15 trillion. Most impressively, DeepSeek v3 cost only $5.58 million to train, while GPT-4 cost about $100 million. That’s a qualitatively significant difference: only the best-funded startups or large tech companies have $100 million to spend on training their AI model, but $5.58 million is well within the reach of many small startups.

Perhaps the biggest difference is that DeepSeek v3 is open-source while GPT-4 is not. The only other open source model from the United States is Llama, developed by Meta. If this feature of DeepSeek v3 is not ringing massive alarm bells in the heads of American technologists and political leaders, it should. It’s a reaffirmation of the central point that there are very few secrets in science and technology that cannot be discovered sooner or later by a technologically advanced country.

One might argue that DeepSeek v3 cost a fraction of the best LLM models to train because it stood on the shoulders of these giants, but that’s precisely the point: like other software, LLM models follow the standard rule of precipitously diminishing marginal cost. More importantly, the open-source, low-cost nature of DeepSeek v3 means that China now has the capability of capturing the world LLM market before the United States as millions of organizations and users make DeepSeek v3 the foundation on which to build their AI. Once again, the quest for security and technological primacy through secrecy would have proved ephemeral, just like it did for nuclear weapons.

What does the entry of DeepSeek v3 indicate in the grand scheme of things? It is important to dispel three myths and answer some key questions. Read more »

infamous lepidopteran, Cydia pomonella, or codling moth. The pom in its species names comes from the Latin root “pomum,” meaning “fruit,” particularly the apple (which is why they’re called pome fruits), wherein you’ll find this worm. It’s the archetypal worm inside the archetypal apple, the one Eve ate. (Not. The Hebrew word in Genesis, something like peri, just means “fruit.” No apple is mentioned. And please, give the mother of all living a break.)

infamous lepidopteran, Cydia pomonella, or codling moth. The pom in its species names comes from the Latin root “pomum,” meaning “fruit,” particularly the apple (which is why they’re called pome fruits), wherein you’ll find this worm. It’s the archetypal worm inside the archetypal apple, the one Eve ate. (Not. The Hebrew word in Genesis, something like peri, just means “fruit.” No apple is mentioned. And please, give the mother of all living a break.)

The Australian author Richard Flanagan is the 2024 winner of the prestigious Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction for his book Question 7. The book is a brilliant weaving together of memory, history, of fact and fiction, love and death around the theme of interconnectedness of events that constitute his life. Disparate connections between his father’s experience as a prisoner of war, the author H.G. Wells, and the atomic bomb all contributed towards making Flanagan the thinker and writer he is today. The book reveals to us his humanity, his love of family and of his home island of Tasmania; it is what Flanagan expects of a book when he says, ‘the words of a book are never the book, the soul is everything’, and this book has ‘soul’.

The Australian author Richard Flanagan is the 2024 winner of the prestigious Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction for his book Question 7. The book is a brilliant weaving together of memory, history, of fact and fiction, love and death around the theme of interconnectedness of events that constitute his life. Disparate connections between his father’s experience as a prisoner of war, the author H.G. Wells, and the atomic bomb all contributed towards making Flanagan the thinker and writer he is today. The book reveals to us his humanity, his love of family and of his home island of Tasmania; it is what Flanagan expects of a book when he says, ‘the words of a book are never the book, the soul is everything’, and this book has ‘soul’.

After I moved from the UK to the US it took me only a couple of years to cede to my friends’ pleas and start driving on the right. When in Rome, and all that. But I still like to irritate Americans by maintaining that we Brits are better at this essential mechanical skill. I mean, when we drive, we

After I moved from the UK to the US it took me only a couple of years to cede to my friends’ pleas and start driving on the right. When in Rome, and all that. But I still like to irritate Americans by maintaining that we Brits are better at this essential mechanical skill. I mean, when we drive, we  Sughra Raza. Ephemeral Apartment Art. Boston January 4, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Ephemeral Apartment Art. Boston January 4, 2025.

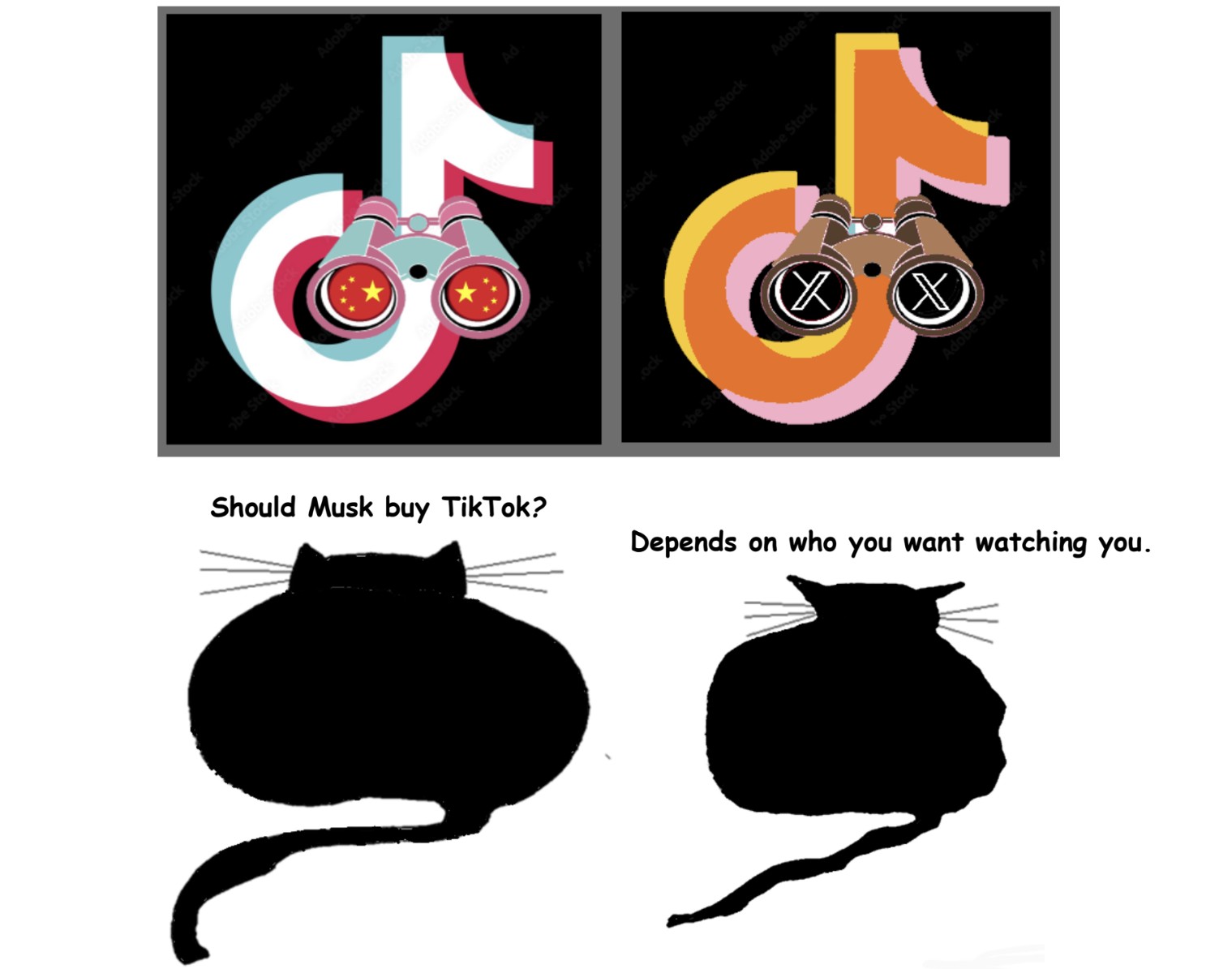

The same media that warned us against Donald Trump now warn us against tuning out. Though our side has lost, we must now ‘remain engaged’ with the minutiae of Mike Johnson’s majority

The same media that warned us against Donald Trump now warn us against tuning out. Though our side has lost, we must now ‘remain engaged’ with the minutiae of Mike Johnson’s majority

What do swimming, running, bicycling, dancing, pole jumping, tying shoelaces, and reading all have in common? According to John Guillory’s new book On Close Reading, they are all cultural techniques; in other words, skills or arts involving the use of the body that are widespread throughout a society and can be improved through practice. The inclusion of reading (and perhaps, tying shoelaces) may come as a surprise, but it is Guillory’s goal in this slim volume to convince us that reading, and in particular, the practice of “close reading,” is a technique just like the others he mentions. This is his explanation for the questions he explores throughout the book—namely, why the practice of “close reading” has resisted precise definition, and why the term itself was so seldom used by the New Critics, the group of theorists most associated with it.

What do swimming, running, bicycling, dancing, pole jumping, tying shoelaces, and reading all have in common? According to John Guillory’s new book On Close Reading, they are all cultural techniques; in other words, skills or arts involving the use of the body that are widespread throughout a society and can be improved through practice. The inclusion of reading (and perhaps, tying shoelaces) may come as a surprise, but it is Guillory’s goal in this slim volume to convince us that reading, and in particular, the practice of “close reading,” is a technique just like the others he mentions. This is his explanation for the questions he explores throughout the book—namely, why the practice of “close reading” has resisted precise definition, and why the term itself was so seldom used by the New Critics, the group of theorists most associated with it. A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.

A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.