by Bill Murray

1

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so avoidable, so banal, so sudden.

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so avoidable, so banal, so sudden.

Our American decline wasn’t born from calamity. It came not in crisis, not under fire, but amid an embarrassment of prosperity, beginning when the United States was the world’s only hyperpower.

Here’s the puzzle: America’s Cold War opponent, the Soviet Union, collapsed in 2001. Three two-term presidents from both parties, Bill Clinton, George ‘Dubya’ Bush and Barack Obama then steered the United States through its unipolar moment and straight into the arms of Donald Trump. How can that possibly be?

This hasn’t been the greatest generation. Okay Boomer?

•

Forty year olds today can scarcely remember the last Soviet leader, Gorbachev. He was an interesting figure (maybe Google him). At the beginning of the 1990s the system he fronted collapsed in an unceremonious face plant.

I visited the Soviet Union three times before it collapsed into history. Its disease was fascinating. Such was latter-day Soviet deprivation that you could lure any Moscow taxi to the curb by brandishing a Marlboro flip-top box.

Its driver exhibited unusual affinity for his windshield wipers—he’d bring them home with him every night. This wasn’t aberrant, or excessive. If he hadn’t, they’d have disappeared by morning. Levis jeans and pantyhose were currency.

The two or three Western standard hotels in both Moscow and Leningrad (soon renamed St. Petersburg) were cauldrons of incipient Capitalism, boiling over with every kind of dealmaking. Carpetbagging accountancies sent young men with fax machines to both cities, who taped their company names to the doors of hotel rooms and got to work. The room you hired might be across the hall from Coopers and Lybrand, or down the corridor from KPMG.

Alas, the accountants hadn’t ridden into town to arrest the collapse of ordinary Russians’ standards of living, or to help raise up the good people who lived there. But then, they never go anywhere to do that.

I remember one long night at the Astoria Hotel bar on St. Isaac’s Square in St. Petersburg, when an American man cancelled his credit card claiming it was stolen, then used it to buy rounds for the house all night. Read more »

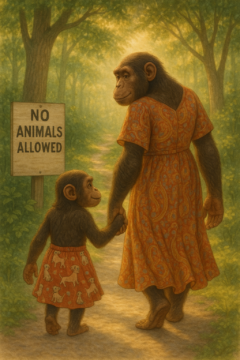

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

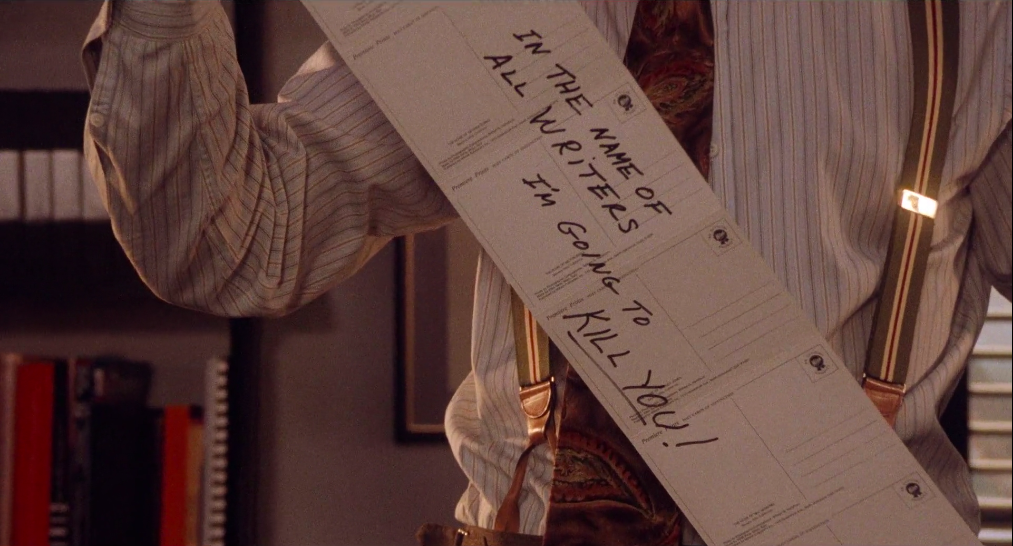

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea: