by Mark Harvey

If the ruler is upright, all will go well even though he gives no orders; but if he is not upright, even though he gives orders they will not be obeyed. —Confucious— Analects 13:6

Pluck a squirming chicken feather by feather; it won’t become obvious until it’s too late. —Attributed to Benito Mussolini

In a recent interview, when asked if she was still proud of her American citizenship with all that’s happening in the US today, the Chilean author Isabel Allende, was vehement: “I am disgusted with a lot of stuff that is happening today, and I am willing to stand and work to make this country what it should be. I want this country to be compassionate and open and generous and happy as it has always been.”

Given that Allende lived much of her life in exile from her native Chile after the military coup in 1973, I was not surprised to hear her passion for a better America and her willingness to stand up and fight for it. In the same interview, Allende describes the heartbreak of leaving everything behind to escape Chile’s dictatorship. Narrating the flight from Santiago to her new home in Venezuela in the 1970s, she said, “I do remember the moment when I crossed the Andes in the plane. I cried in the plane, because I knew somehow instinctively that this was a threshold, that everything had changed.”

But perhaps the paramount statement Allende makes in the interview given the chaos and cruelty wrought on America by this administration is this:

Although things happened very quickly in Chile, we got to know the consequences slowly, because they don’t affect you personally immediately. Of course, there were people who were persecuted and affected immediately, but most of the population wasn’t. So you think: Well, I can live with this. Well, it can’t be that bad. So you are in denial for a long time, because you don’t want things to change so much. And then one day it hits you personally.

What I’ve noticed in recent reading is that some of the people most alarmed by the undisguised fascism of President Trump and his minions are immigrants who have witnessed the speed with which authoritarian movements can seize a nation by its throat: immigrants who fled tyrants for the promised freedom of the United States. The corollary is how lethargic and oblivious many native-born Americans are to the recent violations of our institutions, our morals, and our image in the world. Aesop is fairly shouting through the ages for us to quit being stupid lambs trusting the hungry wolves—to quit being the lazy grasshoppers with winter coming. Read more »

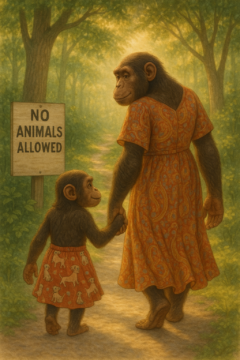

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so

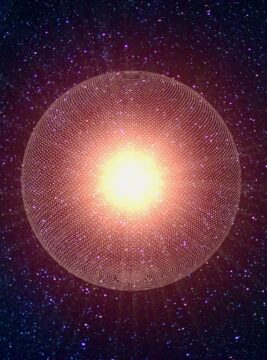

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

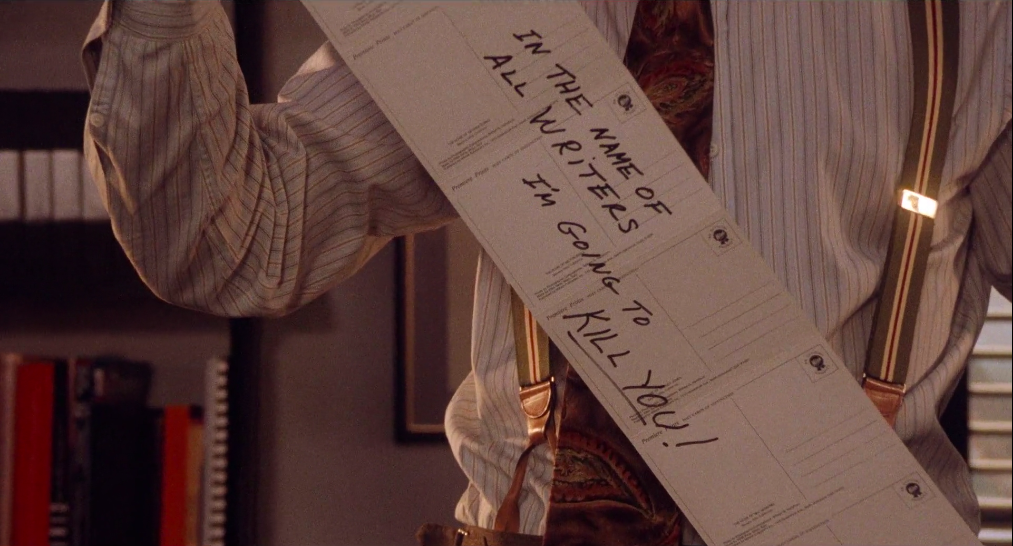

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea: