by Derek Neal

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

So this is how the words work, but what do they say? After reading the first two books in the collection, which together are called The Other Name, the best way I can explain it is by quoting a passage from the book itself:

and that’s how it also is with all the paintings by other people that mean anything to me, it’s like it’s not the painter who sees, it’s something else seeing through the painter, and it’s like this something is trapped in the picture and speaks silently from it, and it might be one single brushstroke that makes the picture able to speak like that, and it’s impossible to understand, I think, and, I think, it’s the same with the writing I like to read, what matters isn’t what it literally says about this or that, it’s something else, something that silently speaks in and behind the lines and sentences (italics mine)

The narrator who is talking, an elderly painter named Asle who lives in rural Norway, spends much of the book like this, thinking about his paintings and trying to explain what they mean. He is unable to explain their meaning, however, because language and painting are two different things, and something gets lost in translation. What he says about writing takes things even further, suggesting that words don’t mean what we say they mean—“what matters isn’t what it literally says about this or that, it’s something else, something that silently speaks in and behinds the lines and sentences.” I would like to suggest that this is the true subject of Fosse’s book (or at least the first two that I’ve read), the idea that words do not mean what we say they mean, but something else, something behind the words.

Fosse’s challenge, of course, is to express this idea through language. How do we say one thing with words that mean something else? Read more »

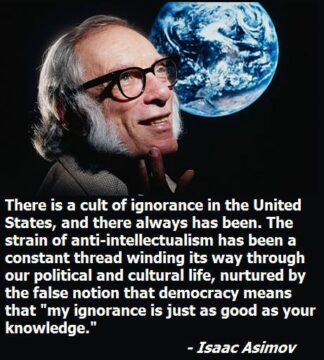

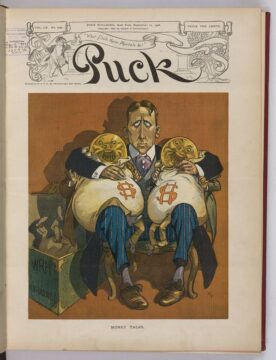

As atrocious, appalling, and abhorrent as Trump’s countless spirit-sapping outrages are, I’d like to move a little beyond adumbrating them and instead suggest a few ideas that make them even more pernicious than they first seem. Underlying the outrages are his cruelty, narcissism and ignorance, made worse by the fact that he listens to no one other than his worst enablers. On rare occasions, these are the commentators on Fox News who are generally indistinguishable from the sycophants in his cabinet, A Parliament of Whores,” to use the title of P.J. O’Rourke’s hilarious book. (No offense intended toward sex workers.) Stalin is reputed to have said that a single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic. Paraphrasing it, I note that a single mistake, insult, or consciously false statement by a politician is, of course, a serious offense, but 25,000 of them is a statistic. Continuing with a variant of another comment often attributed to Stalin, I can imagine Trump asking, “How many divisions do CNN and the NY Times have.”

As atrocious, appalling, and abhorrent as Trump’s countless spirit-sapping outrages are, I’d like to move a little beyond adumbrating them and instead suggest a few ideas that make them even more pernicious than they first seem. Underlying the outrages are his cruelty, narcissism and ignorance, made worse by the fact that he listens to no one other than his worst enablers. On rare occasions, these are the commentators on Fox News who are generally indistinguishable from the sycophants in his cabinet, A Parliament of Whores,” to use the title of P.J. O’Rourke’s hilarious book. (No offense intended toward sex workers.) Stalin is reputed to have said that a single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic. Paraphrasing it, I note that a single mistake, insult, or consciously false statement by a politician is, of course, a serious offense, but 25,000 of them is a statistic. Continuing with a variant of another comment often attributed to Stalin, I can imagine Trump asking, “How many divisions do CNN and the NY Times have.”

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013.

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013. It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.