by Mark R. DeLong

In February, after a month-long consideration, I set my New Year’s resolutions into a five-by-five grid. I made a BINGO card—twenty-four resolutions plus the FREE space. It was my attempt to gamify the whole tired resolution process that I’ve failed at so well. Surprisingly the trick seems to have worked, at least partially.

In February, after a month-long consideration, I set my New Year’s resolutions into a five-by-five grid. I made a BINGO card—twenty-four resolutions plus the FREE space. It was my attempt to gamify the whole tired resolution process that I’ve failed at so well. Surprisingly the trick seems to have worked, at least partially.

One of my BINGO New Year’s resolutions was to write more letters. In fact, that was the first thing I thought of when I compiled my list and so it occupies under the “B”, one (to use BINGO-caller’s lingo). Activities have implications, I told myself, and “doing stuff teaches habits that transcend the things you do. Sure, some of my items look to-do-ish, but they can also lead to virtues.” That message headed up a post entitled “The Fate of Letters,” and I now wonder whether there was some subtle prognostication in the works.

Letter writing has begun to teach me some things.

“One thing about your letter,” someone told me “it’s so hard to read your handwriting.” He was referring to my handwritten note to North Carolina’s US Senator Thom Tillis, written as the new administration was winding up the wrecking ball and Congress sat in the bleachers, silently watching. “In the Senator’s office,” he continued, “they’d not bother to read it, I’m afraid.” (I was glad to have provided my readers a transcript.) And it is true, my handwriting is bad but not illegible. Scores of students have trudged through my comments squeezed into margins and in closing notes on their papers. Only occasionally have I had to “translate.”

Three of my recent letter recipients have commented (not exactly complained) about my writing, too. One, a physician, admitted his handwriting was about as scrawly and awful as mine. Another commented, “It was a pleasure to decipher your handwriting—not as bad as mine but a challenge nonetheless.” Even in a bewilderment of inky swirls and stabs, some readers were able to find a certain pleasure.

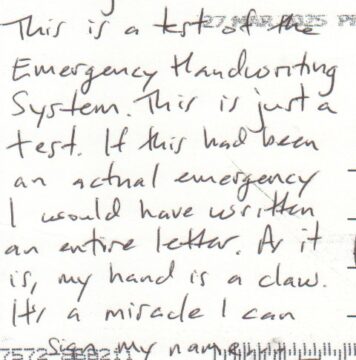

Another recipient sent me a postcard response, which he labelled a “test of the Emergency Handwriting System.” Read more »

In the context of growing concern about educational equity, the persistent racial disparities associated with the Specialized High School Admissions Test in New York City continue to spark debate. As cities and school systems nationwide reconsider the role of standardized testing, the story of the origins of this test shed light on how deeply embedded policies can appear neutral while, in reality, reinforcing inequality.

In the context of growing concern about educational equity, the persistent racial disparities associated with the Specialized High School Admissions Test in New York City continue to spark debate. As cities and school systems nationwide reconsider the role of standardized testing, the story of the origins of this test shed light on how deeply embedded policies can appear neutral while, in reality, reinforcing inequality.

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

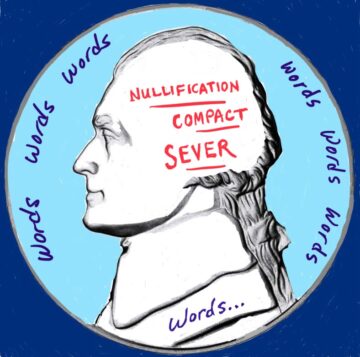

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

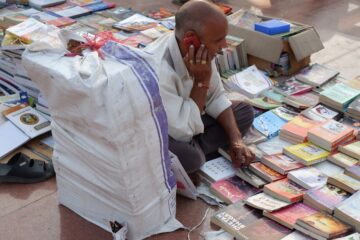

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.