by Scott Samuelson

Though I can’t say that I’ve made any great effort to learn how to meditate or be mindful, the experiences I’ve had have left me cold. Not only am I no good at emptying my mind, I don’t want to empty my mind. I enjoy thinking. Plus, the only times I’ve been anything like “mindful” have been precisely the times when I wasn’t at all focused on being mindful.

While an enviously calm slow breathy voice is intoning, “Breathe in . . . breathe out . . . focus on each breath . . . let go of your thoughts,” I’m thinking, “Can I consciously let go of consciousness? Wait, I’m thinking about not thinking—stop that. Now I’m thinking about thinking about not thinking. Why am I trying to let go of my thoughts, anyway? Isn’t not-thinking what evil people want you to do? Also, I’m beginning to feel light-headed.” It doesn’t help that I’ve hated sitting cross-legged on the floor ever since kindergarten.

Still, I like the idea of a meditative practice that makes use of the one thing that we’re always doing—unless we’re underwater or dead. Like anyone, I can go down bad mental rabbit holes and am prone to all the clingy egocentrism that spiritual traditions rail against. I could use a calming mental discipline—so long as it doesn’t involve trying to space out with my fingers in a weird formation.

So, I decided to come up with my own breathing meditation. After a few months of trying it out, I’m pleased to say that it works marvelously and avoids the pitfalls of my previous experiences.

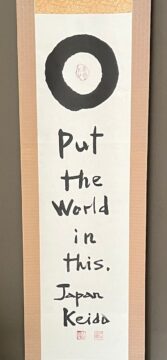

Friends inform me that it’s actually a form of Zen meditation. That makes sense, because all the good original ideas I’ve ever had turn out to be unoriginal. Also, whenever I’ve read Zen poets or philosophers, or wandered in actual Zen gardens, I’ve felt like I was in the presence of something usefully useless. Read more »

In my last

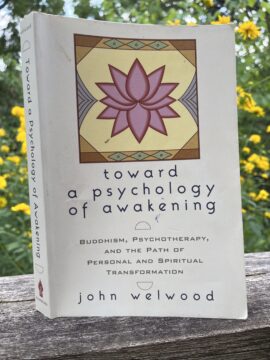

In my last  Vitamins and self-help are part of the same optimistic American psychology that makes some of us believe we can actually learn the guitar in a month and de-clutter homes that resemble 19th-century general stores. I’m not sure I’ve ever helped my poor old self with any of the books and recordings out there promising to turn me into a joyful multi-billionaire and miraculously develop the sex appeal to land a Margot Robbie. But I have read an embarrassing number of books in that category with embarrassingly little to show for it. And I’ve definitely wasted plenty of money on vitamins and supplements that promise the same thing: revolutionary improvement in health, outlook, and clarity of thought.

Vitamins and self-help are part of the same optimistic American psychology that makes some of us believe we can actually learn the guitar in a month and de-clutter homes that resemble 19th-century general stores. I’m not sure I’ve ever helped my poor old self with any of the books and recordings out there promising to turn me into a joyful multi-billionaire and miraculously develop the sex appeal to land a Margot Robbie. But I have read an embarrassing number of books in that category with embarrassingly little to show for it. And I’ve definitely wasted plenty of money on vitamins and supplements that promise the same thing: revolutionary improvement in health, outlook, and clarity of thought. Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).