by Christopher Horner

Become That which You Are —Nietzsche.

What is it to lead a free life? Perhaps it is doing what we want with the minimum of external constraints, so we can follow our desires. Also to be free from anything within us that would prevent us from choosing wisely and acting effectively. I don’t want to bungle an action, I don’t want to get things wrong that might lead me to misread a situation, and I don’t want to be knocked off track by some outburst of the irrational, blind anger or a neurotic compulsion that reaches me from my past. The ideal of a free life includes in it the notion that I can to identify with my actions as my own, to stand by them, as it were.

We picture the rational self that wills, as somehow brightly lit in the conscious mind: I know, I choose, I act, and I say: I did that. The darkness is in the unconscious, and we need the light to choose freely. However, this image of the free self is at best incomplete. [1] We know that we are being pushed in all sorts of ways, even – perhaps especially – when we think we are making a free choice. I choose A over B: to marry or not; to go on holiday here and not there; to go for a walk; to buy that laptop. Are these free, independent choices? How did I come to have just these desires, here and now? My desire for A over B was conditioned by who I came to to be, and my goals are embedded in my biology and in my place and time in history. Since desires aren’t simple and basic can I say I am free when I act on them? If not it would appear that responsibility, and the praise or blame that goes with it, are just empty words.

‘Ought implies can’

The phrase comes from is Immanuel Kant, who was much exercised by the question, as he saw that morality implies freedom. Since my reasons for doing something are also causes, and are the outcomes of the push and pull of social life, it looks like my inclinations are anything but free, if we imagine that to mean that I could have chosen to do something else. We may feel free, but that isn’t proof that we are free.

Indeed, for Kant, morality had to come from a sense of duty that goes against inclination, that acts from something other than ‘what I want’. For Kant, that duty is a sign that we are not only inhabitants of the world of necessity, but also subjects able to act freely, on principle, and thus morally. We are in a way, inhabitants of two worlds: the causal one of ordinary desire and the free one of duty. His controversial answer, and the arguments it provoked, we won’t follow here. Yet there are phenomena that we may come to see as signs that he may have been on the right track..

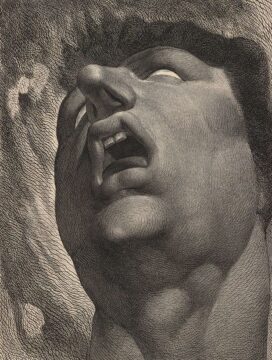

I’ve mentioned the experience of feeling free in our actions, and that that feeling might be misleading us. But what about the other way around? There are surely times when we feel that we must do something, so much so that it may make us feel fated to do that thing. Falling in love, for instance. If you have had that experience, I would suspect that you didn’t experience it as a choice you were making; you may even have felt it as a kind of thing that you just couldn’t stop, as a fate, indeed. And its not necessarily the case that you found the experience pleasurable. It might be more like a enjoyment as pleasure plus pain.[2] I want to suggest that it is in moments like this that we act freely, if we ever do.

What makes a decision mine?

We are looking in the wrong place, if we expect to find the free self in the quotidian choices of daily of life. Instead, we should look to the unconscious for freedom. In significant experiences that don’t feel like free decisions, like falling in love, committing to a political cause, pursuing an artistic vocation, we act freely, while feeling we could do no other thing. This is because we have made the decision unconsciously, before we consciously ‘know’ it. The decision never happens in the present.[3] If we reject the spontaneous feeling of freedom as an illusion we are left with the subject, emptied of what Kant called its ‘pathological’ motivations, which are ruled by causality.

Of course it may be objected here that the unconscious, too, is the product of natural causality. Yet the deeper demand that we act in ways that go against our felt inclination may be a sign that if anything is ‘ours’, then these acts are. We catch desires: they are more contagious than the common cold – all our desires are desires of the Other. But the Thing that really drives me has another meaning. It is The Thing that is uniquely my own. They make the poet, the painter and the lover something more than the shopper in the Mall. They allow us to become what Nietzsche meant when he encouraged us to become that which we are.

***

[1] I’ve discussed the problem of freedom and determinism on 3QD before – here , for instance.

[2] One of the words commonly used by psychoanalysts for this experience is French: Jouissance.

[3] The fact that others often notice what is driving us and what we mean when we speak, long before we do ourselves, might help to dispel the image of the unconscious as a dark deep well within us. The unconscious, on the contrary, is with us in all we do, in slips of the tongue, bungled actions as well as in the things that seem to constitute our fate: it is caught up with our being as subjects of language, entangled in the web of words and actions.

Books consulted:

Alenka Zupancic: Ethics Of The Real: Kant And Lacan, London, Verso Books 1995.

Slavoj Zizek: Freedom, A Disease Without Cure, London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2023.