by Dilip D’Souza

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.

But as the name might suggest, it is a place where you see some incredible night skies, and that’s really why it is spectacular. Last night was partly cloudy, but I saw the Milky Way arcing high above my head, as well as plenty of stars I would never see at home in Bombay. The dark sky is the reason there are two large optical telescopes here, operated by the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA), in Bangalore.

And under that dark sky last night, taking several photographs of the stars that I’m inordinately pleased with, I also had plenty of time to ruminate. At one point, it was probably being at this IIA facility that had me thinking briefly – of all things – of a temple in Ayodhya. That’s the temple to Lord Ram, consecrated by the Prime Minister in January last year.

One day a few months later, a shaft of sunlight fell directly on the idol of Lord Ram in that temple, making for a gorgeous sight. At the time, I was reminded of a photograph I have somewhere, that I took in a cavern at the ancient fort of Masada, in Israel. A man stands there, reading a book, and there’s a shaft of sunlight directly on him, just like Lord Ram in Ayodhya. While that photograph owed everything to a hole in the roof of the cavern, the sunbeam in Ayodhya was a little more complex. Read more »

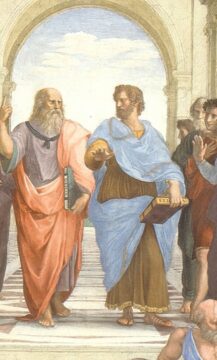

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.

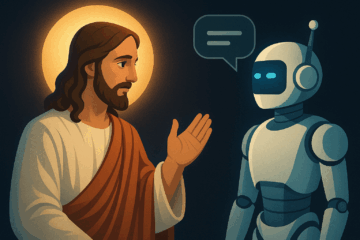

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have