by Fabio Tollon

We take words quite seriously. We also take actions quite seriously. We don’t take things as seriously, but this is changing.

We live in a society where the value of a ‘thing’ is often linked to, or determined by, what it can do or what it can be used for. Underlying this is an assumption about the value of “things”: their only value consists in the things they can do. Call this instrumentalism. Instrumentalism, about technology more generally, is an especially intuitive idea. Technological artifacts (‘things’) have no agency of their own, would not exist without humans, and therefore are simply tools that are there to be used by us. Their value lies in how we decide to use them, which opens up the possibility of radical improvement to our lives. Technology is a neutral means with which we can achieve human goals, whether these be good or evil.

In contrast to this instrumentalist view there is another view on technology, which claims that technology is not neutral at all, but that it instead has a controlling or alienating influence on society. Call this view technological determinism. Such determinism regarding technology is often justified by, well, looking around. The determinist thinks that technological systems take us further away from an ‘authentic’ reality, or that those with power develop and deploy technologies in ways that increase their ability to control others.

So, the instrumentalist view sees some promise in technology, and the determinist not so much. However, there is in fact a third way to think about this issue: mediation theory. Dutch philosopher Peter-Paul Verbeek, drawing on the postphenomenological work of Don Ihde, has proposed a “thingy turn” in our thinking about the philosophy of technology. This we can call the mediation account of technology. This takes us away from both technological determinism and instrumentalism. Here’s how. Read more »

If Joan Didion were alive today, she might write an essay about Prince Harry and include it in an updated version of Slouching Towards Bethlehem. She might write a passage like the one she wrote about Howard Hughes:

If Joan Didion were alive today, she might write an essay about Prince Harry and include it in an updated version of Slouching Towards Bethlehem. She might write a passage like the one she wrote about Howard Hughes:

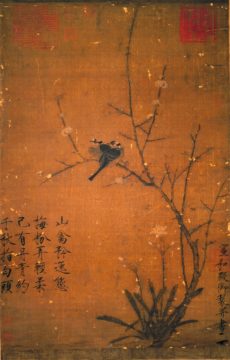

Ada Beams. Landscape Somewhere in France, 2022.

Ada Beams. Landscape Somewhere in France, 2022.

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge  Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s

Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s

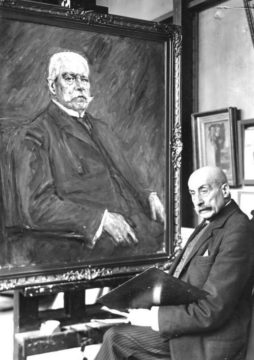

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022.

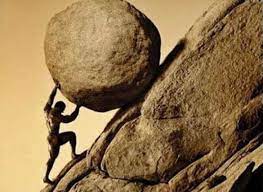

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022. If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.