by Rafaël Newman

It’s been 90 years since Hitler was appointed German Chancellor, on January 30, 1933, despite his party, the NSDAP, having failed to achieve a majority in the elections to the Reichstag held the previous year; so naturally I’ve been thinking about Max Liebermann.

Born decades before the establishment of the German Empire, or Second Reich, in 1871, the painter Max Liebermann (July 20, 1847—February 8, 1935) was to die just as the Third Reich was rising to its hideous feet. Liebermann was a pillar of the German art world—or rather, he had become one by 1933, when he resigned from the Prussian Academy of Arts, the body he had served as president, but which had now fallen into line with the Nazis and had ceased exhibiting works by Jewish artists.

Max Liebermann was himself Jewish, but by the time of his death at the age of 87 he had long been accepted in the wider German bourgeois society into which he had been born, and which had persisted in its Prussian, Wilhelmine, and Weimar variations. After a rocky start to his career with scandalously “ugly” scenes of working-class life and “blasphemous” depictions of religious motifs, Liebermann would go on to play a leading role in the Berlin Secession, the fin-de-siècle movement opposed to the strictures of academic painting, which championed Impressionism and Realism and counted among its members such notable artists as Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, Käthe Kollwitz, and Otto Modersohn. Liebermann resisted the Secession’s eventual support for Expressionism, however, which moved him towards the conservative camp and prepared his entry into the Academy, the establishment’s artistic watchdog, and the mainstream of German culture.

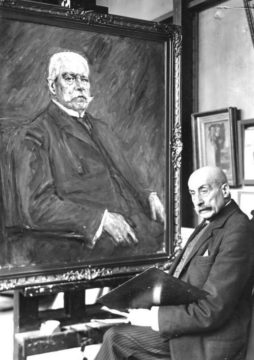

Having commenced his career depicting scenes of life among the common folk and painting Dutch-inspired landscapes, Liebermann later turned his hand to portraiture. To have one’s likeness rendered by him eventually became a must for members of Prussian high society. In 1927 Liebermann was given a prestigious commission: to paint Reichspräsident Paul von Hindenburg. Protocol required that Liebermann address Hindenburg as “Your Excellency” and that he acknowledge the honor bestowed upon him, the painter, by the task; instead, legend has it, Hindenburg addressed Liebermann with the ritual honorific, and declared himself honored by the occasion.

That same year, on Liebermann’s 80th birthday, Thomas Mann, another once and future pillar of German society, described the painter as the epitome of his native city, the once and future capital. “In Liebermann I admire Berlin,” wrote Mann. “I think it marvelous that he speaks the lively, cheeky Berlin dialect, frankly and unaffectedly; and when I visit him in his house on Pariser Platz, I feel myself at the nexus of jovial forces, in a prestigious location rich in symbolism, at the residence of the genius loci.”

Liebermann’s house (or Palais) on Pariser Platz, in the shadow of the Brandenburg Gate, had been the family estate, and had passed into Max’s possession upon his father’s death. It was the painter’s principal winter residence—summers were spent in his villa on the Wannsee—and had itself become such a landmark that it had given rise to a popular bon mot: “Where does the painter Liebermann live? When you enter Berlin it’s on the left.”

As Berlin expanded, what had once been the entrance to the city now became its center, and Liebermann effectively had a front-row seat to modern German history. During the street fighting that followed the abdication of the Kaiser in 1918, for instance, Liebermann’s house was briefly the site of skirmishes between revolutionaries and monarchists, who had positioned artillery on its grounds; and when, on January 30, 1933, Nazis organized a torch-light parade through the Brandenburg Gate to celebrate Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor by that same Hindenburg who had sat for Liebermann, their route took them right past the Palais. Liebermann’s rueful comment on watching the procession has become proverbial. In his “lively, cheeky Berlin dialect,” he remarked:

Ick kann jar nich soville fressen, wie ick kotzen möchte.

“I can’t eat nearly as much as I would like to vomit.”

*

The Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM) in Berlin, on Unter den Linden, the same grand boulevard that had once been Liebermann’s address, is installed in what was an armory before serving as the royal Prussian army museum and passing into the hands of the Nazis, and then the GDR regime. The DHM is currently featuring an exhibition under the slogan “Roads not Taken.” Subtitled “Things Could Have Turned Out Differently. German Caesuras 1989–1848”, the show aims to reverse the teleological regard of conventional historiography—the view that necessity had dictated the course of events as they were subsequently set down in the annals—with an appreciation for contingency, for the potential that underpins the actual.

This rhetorical reversal of perspective is literalized in the exhibition’s timeline, which runs from the “peaceful revolution” that culminated in the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 backwards, to the revolutions of 1848—the year after Max Liebermann’s birth, as it happens—when German political history might have run a very different course: if the movement for constitutional democracy had been successful, and the Second Reich had not come into being; if Prussian militarism had not compounded the nascent nationalist imbroglio in Central Europe, and internecine monarchic rivalry had not led to an arms race with the British Empire; if the First World War had not led to reparation payments, and economic crisis, and the rise of fascism…

And yet for all that, the exhibition is not simply a speculative exercise in “what if”. In his address at the opening of the show, on January 18, the historian Dan Diner ruled out fantasy as a curatorial motive.

“It is important to stress that the exhibition never departs from the ground of reality as it actually occurred. In that sense, what is presented here is not what is known as counterfactual history. All the exhibition does is lean out over the edge of reality as it came into being in order to detect what had been laid down there, far below, and what was germinating. This is the point of view adopted by the exhibition, and thus also the question that it poses: Did it have to turn out the way it did?”

In other words: Did the road on which Liebermann’s house once stood necessarily have to lead, not only to the villa on the Wannsee where the painter spent his summers, but also to another villa with a very different purpose on that same lake, where the destruction of Jewish life in Germany, as in the rest of Europe and, if things had gone to plan, the Nazi-dominated world, was plotted out?