by David J. Lobina

In this misguided series of posts on large language models (LLMs) and cognitive science, I have tried to temper some of the wildest discussions that have steadily appeared about language models since the release of ChatGPT. I have done so by emphasising what LLMs are and do, and by suggesting that much of the reaction one sees in the popular press, but also in some of the scientific literature, has much to do with the projection of mental states and knowledge to what are effectively just computer programs; or to apply Daniel Dennett’s intentional stance to the general situation: when faced with written text that appears to be human-like, or even produced by humans, and thus possibly expressing some actual thoughts, we seem to approach the computer programs that output such prima facie cogent texts as if they were rational agents, even though, well, there is really nothing there!

Naturally enough, many of the pieces that keep coming out about LLMs remain, quite frankly, hysterical, if not delirious. When one reads about how a journalist from the New York Times freaked out when interacting with a LLM because the computer program behaved in the juvenile and conspiratorial manner that the model no doubt “learned” from some of the data it was fed during training, one really doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry (one is tempted to tell these people to get a grip; or as Luciano Leggio was once told…).[i]

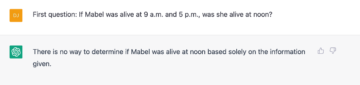

More importantly, when people insist that LLMs have made passing the Turing Test boring and have met every challenge from cognitive science, and even that the models show that Artificial General Intelligence is already here (whatever that is; come back next month for my take), one must at least raise one eyebrow. Here’s a recent, fun interaction with ChatGPT, inspired by one Steven Pinker (DJ stands for you-know-who):

So, no, LLMs definitely don’t exhibit general intelligence, and they haven’t passed the Turing Test, at least if by the latter we mean partaking in a conversation as a normal person would, with all their cognitive quirks and what not. Read more »

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

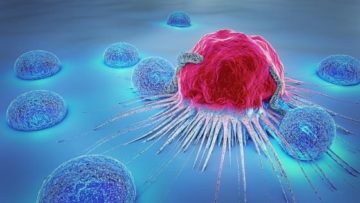

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes.

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes. Ideas often become popular long after their philosophical heyday. This seems to be the case for a cluster of ideas centring on the notion of ‘lived experience’, something I first came across when studying existentialism and phenomenology many years ago. The popular versions of these ideas are seen in expressions such as ‘my truth’ and ‘your truth’, and the tendency to give priority to feelings over dispassionate factual information or even rationality. The BBC is running a radio series entitled ‘I feel therefore I am’ which gives a sense of the influence this movement is having on our culture, and an NHS trust has apparently advertised for a ‘director of lived experience’.

Ideas often become popular long after their philosophical heyday. This seems to be the case for a cluster of ideas centring on the notion of ‘lived experience’, something I first came across when studying existentialism and phenomenology many years ago. The popular versions of these ideas are seen in expressions such as ‘my truth’ and ‘your truth’, and the tendency to give priority to feelings over dispassionate factual information or even rationality. The BBC is running a radio series entitled ‘I feel therefore I am’ which gives a sense of the influence this movement is having on our culture, and an NHS trust has apparently advertised for a ‘director of lived experience’.

Sughra Raza. Pavement Expressionism. June 2014.

Sughra Raza. Pavement Expressionism. June 2014.

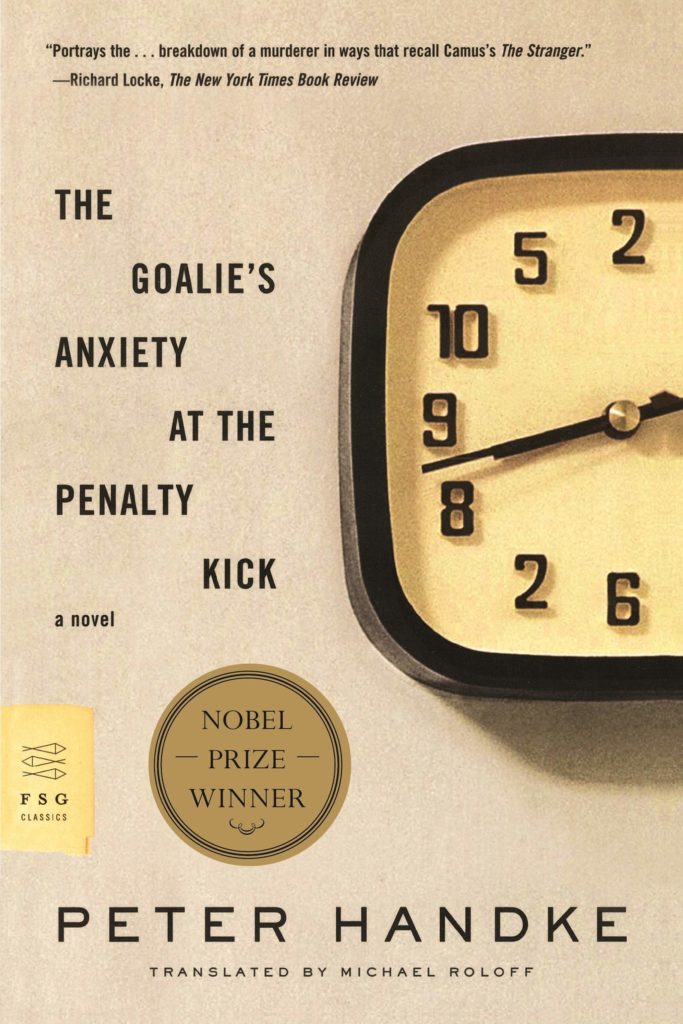

A few months ago, I wrote about Karl Ove Knausgaard’s Spring and how his focus in this book is the examination of two worlds: the physical world that exists apart from us (the outside world), and the world of meaning and significance that is overlaid on top of this world through language and consciousness (the inner world). Knausgaard’s main goal seems to be to shock us out of our habitual, unreflective existence, and to bring about an awareness with which we can experience our lives in a different way.

A few months ago, I wrote about Karl Ove Knausgaard’s Spring and how his focus in this book is the examination of two worlds: the physical world that exists apart from us (the outside world), and the world of meaning and significance that is overlaid on top of this world through language and consciousness (the inner world). Knausgaard’s main goal seems to be to shock us out of our habitual, unreflective existence, and to bring about an awareness with which we can experience our lives in a different way.

A couple months back, I wrote

A couple months back, I wrote