by Akim Reinhardt

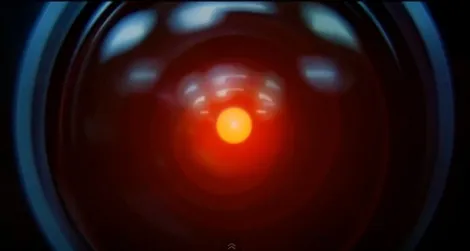

The ChatGPT Bot has changed everything! That’s the basic vibe I’m getting from frantic press reports, early return think pieces, and even public-facing academicians. Specifically, this new, free AI software, only a few weeks old and still improving, is already churning out high school-quality essays on just about any subject a teacher might assign, and it now stands as a real threat to the very concept of high school and even college term papers.

As a History professor myself, I suppose I should be duly panicked. However, I don’t see the rise of the bot as something to fear or even resent. That’s not to say there isn’t cause for concern. There absolutely is, and adjustments are required. But my own personal history leads me to see charlatanism as something you simply have to deal with. Growing up in New York City, we learned to dodge it from a young age, with an understanding that it was up to us to spot it. Suckers may not deserve to get taken in a sidewalk game of Three Card Monty, as hustlers love to claim, thereby muddying their own immorality. However, even if the victims are to be pitied, suckers fill an ecological niche: they function as an object lesson to the rest of us: Don’t be like them. Don’t be a chump. I also wasn’t a very good undergraduate college student, though I didn’t cheat (too much pride, not enough giving a shit).

Add it all up, and I’m primed to stop cheaters. I know how a lazy student thinks, and I’m always on the alert, guarding against getting taken. I’ve also been designing and grading college student assignments for close to a quarter-century. So for me, this new AI bot is not scarey, or even revolutionary. It’s just the latest con for those who would seek to dupe me out of my most prized professional possession: passing grades. A quick rundown shows how the academic bunko game has changed just in my time as a professor. Read more »

I’m going to date myself in a significant way now: when I was in high school, we had to use books of trigonometric tables to look up sine and cosine values. I’m not so old that it wasn’t possible to get a calculator that could tell you the answer, but I’m assuming that the rationale at my school was that this was cheating in some way and that we needed to understand how actually to look things up. I know that sounds quaint now. I also remember when I used an actual book as a dictionary to look up how to spell words. Yes, youth of today, there were actual books that were dictionaries, and you had to find your word in there, which could be challenging if you didn’t know how to spell the word to begin with.

I’m going to date myself in a significant way now: when I was in high school, we had to use books of trigonometric tables to look up sine and cosine values. I’m not so old that it wasn’t possible to get a calculator that could tell you the answer, but I’m assuming that the rationale at my school was that this was cheating in some way and that we needed to understand how actually to look things up. I know that sounds quaint now. I also remember when I used an actual book as a dictionary to look up how to spell words. Yes, youth of today, there were actual books that were dictionaries, and you had to find your word in there, which could be challenging if you didn’t know how to spell the word to begin with.

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Sughra Raza. Cactus In My Window.

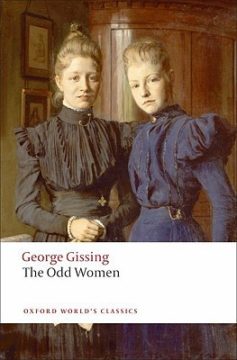

Sughra Raza. Cactus In My Window. This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them.

This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them.

It’s halfway through the month of December and New York is filled with pine boughs and small yellow bells and horse-drawn carriages and scarves. We are seated on the edge of the fountain in Washington Square Park, though this time of year the water has been shut off. A group of five skateboarders are practicing jumps in the large basin. We just bought a pre-rolled joint from one of the stands in the park, of which there are many. But we only buy from one of them. Weed is legal in the city now, but it’s not legally sold, so it can be questionable, and you never want “questionable” when you’re prone to paranoia. We trust the woman who runs this stand, though, because we know where she buys it and she has a rainbow flag on the front of her table.

It’s halfway through the month of December and New York is filled with pine boughs and small yellow bells and horse-drawn carriages and scarves. We are seated on the edge of the fountain in Washington Square Park, though this time of year the water has been shut off. A group of five skateboarders are practicing jumps in the large basin. We just bought a pre-rolled joint from one of the stands in the park, of which there are many. But we only buy from one of them. Weed is legal in the city now, but it’s not legally sold, so it can be questionable, and you never want “questionable” when you’re prone to paranoia. We trust the woman who runs this stand, though, because we know where she buys it and she has a rainbow flag on the front of her table.

Numerology can easily result from free association and, given its assertions, it certainly seems like it has been. In any case, I thought I’d try my hand at it.

Numerology can easily result from free association and, given its assertions, it certainly seems like it has been. In any case, I thought I’d try my hand at it.

In 1995, I made two Christmas mixtapes that I labeled A Very Mary Christmas. I had recently gone through a period of wondering whether it made sense to go on celebrating Christmas, given that I’d stopped believing in the Christian story years earlier. In particular, I’d thought about whether I wanted to go on listening to Christmas music—especially the old traditional carols I love, many of which have explicitly religious lyrics. In the end, I decided that there were other good reasons to celebrate the time around the winter solstice. I made the mixtapes in a spirit of enjoying winter and celebrating both the darkness and the light to be found in family and friends. I kept some of the traditional carols (some only in instrumental versions) and religious music—Handel’s Messiah, for example. In addition, I included music that’s not traditionally considered Christmas music or even winter music; hence the now mildly embarrassing substitution of Mary for Merry.

In 1995, I made two Christmas mixtapes that I labeled A Very Mary Christmas. I had recently gone through a period of wondering whether it made sense to go on celebrating Christmas, given that I’d stopped believing in the Christian story years earlier. In particular, I’d thought about whether I wanted to go on listening to Christmas music—especially the old traditional carols I love, many of which have explicitly religious lyrics. In the end, I decided that there were other good reasons to celebrate the time around the winter solstice. I made the mixtapes in a spirit of enjoying winter and celebrating both the darkness and the light to be found in family and friends. I kept some of the traditional carols (some only in instrumental versions) and religious music—Handel’s Messiah, for example. In addition, I included music that’s not traditionally considered Christmas music or even winter music; hence the now mildly embarrassing substitution of Mary for Merry.