by Marie Snyder

Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s significantly different and can be useful in recognizing that we’re all innately different kinds of people. This awareness can help us get along in this world and maybe even find love, or at least a better roommate.

Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s significantly different and can be useful in recognizing that we’re all innately different kinds of people. This awareness can help us get along in this world and maybe even find love, or at least a better roommate.

Dividing people into types based on intrinsic tendencies has been around for millennia, born of scrutinized observations of human nature. Ayurvedic Doshas were recorded about 3,000 years ago identifying people who are Vata (energetic but scattered), Pitta (systematic and ambitious, but dogmatic), or Kapha (methodical but slow moving). The four humours came around 500 years later with Alcmaeon of Croton to differentiate those who tend to be sanguine, phlegmatic, choleric, or melancholic. If you think of those categories long enough, you can easily find yourself playing a game of slotting your friends and family under each term.

Then Jung wrote Psychological Types in 1921, outlining opposing traits along three continuums: extraverted/introverted, sensing/intuitive, and thinking/feeling. (That last one might be better updated to task-oriented/people-oriented.) Although it produces only nine specific types, the continuum set-up provides infinite possibilities within each set of four letters. It’s similar to being mainly melancholic with a touch of sanguine, or having a primary and secondary dosha. Jung explains his stance on innate personality:

“The fact that, in spite of the greatest possible similarity of external conditions, one child will assume this type while another that, must, of course, in the last resort be ascribed to individual disposition.”

This typology was popularized by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers who added the perception/judgment continuum and found a market for attaching types to careers. Later the Big 5 added another continuum: sensitive/resilient, and now it’s used by data miners. The fact that companies like Cambridge Analytica use psychographic marketing to influence our purchasing and decisions (and possibly our voting choices), means there’s likely something to understanding people under categories.

These are all similar tactics toward understanding our nature. Where a horoscope looks at the stars and our birthdate to make predictions, these “type delineators” look at each person and then merely presents a label to name the set of characteristics. Where Myers-Briggs deserves criticism is when it’s used to predict career goals. Even if all rocket scientists are ISTJs doesn’t mean all ISTJs will enjoy being a rocket scientist. That’s an affirming the consequent error. And we no longer do as much blood-letting as we once did. But we do still strive to find a balance within the self.

I wonder if that quest for a balanced self isn’t too much to ask.

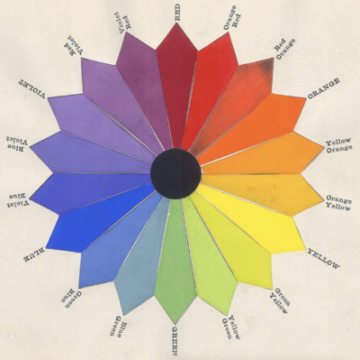

There are two other options: seeking a complementary or analogous type for some shared balance. Instead of being on our own on this, perhaps we work better together in pairs or groups, creating a beautiful colour scheme together. Maybe instead of balancing our humors or integrating the opposing type in a process of individuation, we need to find other types to help us balance out as a collective. We often see this in sitcoms with best buddies having a serious calm type paired with a crazy wild type and together they resolve the inciting incident, and we can likely think of couples in real life who operate as a pair. My mom was brilliant but scattered, unable to remember details of any story or explanation, but my dad was always there to flush out the specifics for us. The other option might be, instead of pushing introverts to get out there more or trying to quiet down extroverts, people can find similar types to be with, where they feel at home as they are. This is less often portrayed in entertainment because a room of people happily reading books doesn’t make for good TV.

There are two other options: seeking a complementary or analogous type for some shared balance. Instead of being on our own on this, perhaps we work better together in pairs or groups, creating a beautiful colour scheme together. Maybe instead of balancing our humors or integrating the opposing type in a process of individuation, we need to find other types to help us balance out as a collective. We often see this in sitcoms with best buddies having a serious calm type paired with a crazy wild type and together they resolve the inciting incident, and we can likely think of couples in real life who operate as a pair. My mom was brilliant but scattered, unable to remember details of any story or explanation, but my dad was always there to flush out the specifics for us. The other option might be, instead of pushing introverts to get out there more or trying to quiet down extroverts, people can find similar types to be with, where they feel at home as they are. This is less often portrayed in entertainment because a room of people happily reading books doesn’t make for good TV.

A further question is what makes us different by type? Where does this individual disposition come from? Our understanding of it all is still focused on bodily fluids, but now we’re less focused on mucus and bile and much more interested in the role of specific hormones and neurotransmitters in our cerebrospinal fluid. Neuroplasticity has made it clear it’s all a mix of nature and nurture, so we may never pinpoint why I’m an INTP.

Perhaps it’s more important to focus on what to do with this information once we have it.

Used as Jung intended, to understand our differences in order to better accept ourselves and interact with others, it appears to stand the test of time. It can be useful to consider that we’re all a bit different in fundamental ways. We can understand ourselves and accept these core attributes in order to help ourselves better integrate with the world.

It’s not too dissimilar from how we understand dog breeds.

I’ve lived with two mutts and a purebred. The purebred was purchased by an old boyfriend explicitly for the personality of that type of breed. But even though the mutts were a mix, they were also chosen for their specific type of assumed attributes. It’s not just about finding non-allergic breeds; we also don’t think twice about asking how much exercise a breed might need, or how well they could manage in a small space or alone for nine hours each day. Most dog-lovers would know better than to get a border collie if they have an apartment and work long hours; that breed needs to run and think and have ongoing challenges or they end up with serious mental health issues. But other breeds can manage the wait and love a cosy living space. We get a certain breed because we expect it to come with a general personality that matches our current lifestyle.

Typology can be used in a similar way. It might not predict our best career move, but it can help us understand why we find lots of noise so irritating when others seem to actually enjoy it. Some are really hyper and thrive on people and might be a good fit with someone calm but a disaster with someone who finds people or too much noise absolutely nerve wracking.

Some dogs with a soft bite are unlikely to harm unless someone worked hard to make them vicious, and others need extremely firm boundaries to keep them from getting too territorial. We each have a nature to us that needs to be worked with, not overruled. People around us can bring out the best in us, or the worst.

Dating apps typically ask a lot about appearances, religious and political affiliations, income, and hobbies. I never dive in for long, finding most bios focus on travel, working out, and food. Not that there’s anything wrong with those interests, but they’re not a good fit for me. But maybe these sites would work better if they focused on questions around what type of people we really are instead of what we’re interested in. We can have identical interests but not gel or have different interests but it just works. Instead, we can ask people directly instead of making hopeful assumptions:

How energetic are you? Do you need daily exercise with someone else, or are you okay if your partner’s energy is very different?

Do you prefer big parties or quiet evenings? Or, more specifically: How many big parties per year would be ideal for you ranging from 0 to 365?

How flexible is your schedule? Do you prefer spontaneous encounters or do you keep to a routine?

What is the time commitment for being with you? How much time is ideal to be with a partner in a week?

Can you tolerate noise well or do you prefer a quiet environment?

Do you need mental challenges to stay sane? Do you love or hate to debate issues?

Do you need a lot of toys, or are you more content with just one good one? Do you need someone to play with you, or do you prefer to play alone or with someone nearby.

Do you regularly pick up your toys, or do you prefer to leave them scattered around because you’re still using them?

Do you like straightforward communication, or do you prefer messages couched in niceties?

Do you need a special diet, or will you eat just about anything? Can you be content eating the same thing every night?

Do you prefer to stay close to home, or will you need more variety in your setting?

Do you fit well in a cosy corner of the room, or do you need miles to roam?

Neurotic, quick to bark from under a table or calm enough to sleep through an intruder?

How territorial/protective are you (with people and with things)?

How hard is your bite?

But then, after all that, it still has to pass the sniff test in real life.

One of my dogs was super friendly with everyone and every dog we met, except for one. He hadn’t had  a negative experience at all with this particular dog, but, out for a walk, I could tell when the enemy was nearby by the low growl and huffing from my dog as they’d turn the corner towards us. I learned a good life lesson from their dynamic. Sometimes people just won’t be that into you even if you’ve done nothing to cause their dislike. The chemistry’s just not right; move on.

a negative experience at all with this particular dog, but, out for a walk, I could tell when the enemy was nearby by the low growl and huffing from my dog as they’d turn the corner towards us. I learned a good life lesson from their dynamic. Sometimes people just won’t be that into you even if you’ve done nothing to cause their dislike. The chemistry’s just not right; move on.

And, some of us are rare breeds, too often misunderstood, maybe seeming a bit neurotic, but that’s just because we’re not living in an ideal environment. How many of us are in a situation that’s giving us mental health issues? Sometimes things are too noisy or quiet or bouncy or tedious for us to really thrive.

We might never be able to get to that perfectly balanced center of things, but we might be able to find a community of acceptance or someone out there to match our weirdness.