by Mary Hrovat

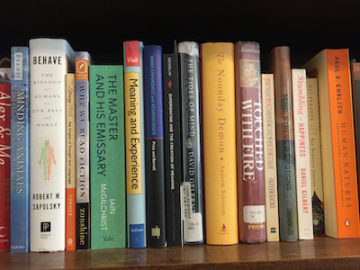

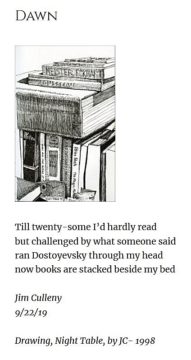

There are many reasons to want to own a book. Most of them are straightforward: you can’t get it at the library, or you read the library’s copy and want your own copy to re-read or consult; you need it on hand as a reference; or it’s so beautiful that you want to be able to look at it whenever you like.

There are also more nebulous reasons for owning books that have to do with hopes, memories, and self-image—perhaps even illusions. I held onto my college textbooks for years after I graduated, even though I didn’t use my degree in my job. I finally got rid of most of them; space is always tight, and textbooks are typically bulky. Overall I suppose it was a good decision, but for years I missed my calculus textbook. I didn’t miss it for any practical reason. I never used calculus. I missed being the kind of person who needs to use calculus. I could probably pick up a calculus textbook easily enough at one of the used book sales held in my town, but there’s another reason I miss that book: It was mine. I carried it to class for four semesters; I worked the problems. It belonged to a past life that I still miss sometimes.

I’ve heard people use the term weeding to refer to the removal of books from library collections. In the collection development course I took in library school, I was taught to use the more formal terms deaccession and deaccessioning. The word withdrawal is also used. I agree that the word weeding isn’t suitable, not because it’s informal but because it suggests that the books being removed were never assets to the collection. I think pruning is better; when I decide to give away (or very occasionally throw away) some of my books, I’m removing things that no longer fit well enough to merit shelf space. Read more »

Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of

Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite.

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite. Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.

Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around