by Mary Hrovat

There are many reasons to want to own a book. Most of them are straightforward: you can’t get it at the library, or you read the library’s copy and want your own copy to re-read or consult; you need it on hand as a reference; or it’s so beautiful that you want to be able to look at it whenever you like.

There are also more nebulous reasons for owning books that have to do with hopes, memories, and self-image—perhaps even illusions. I held onto my college textbooks for years after I graduated, even though I didn’t use my degree in my job. I finally got rid of most of them; space is always tight, and textbooks are typically bulky. Overall I suppose it was a good decision, but for years I missed my calculus textbook. I didn’t miss it for any practical reason. I never used calculus. I missed being the kind of person who needs to use calculus. I could probably pick up a calculus textbook easily enough at one of the used book sales held in my town, but there’s another reason I miss that book: It was mine. I carried it to class for four semesters; I worked the problems. It belonged to a past life that I still miss sometimes.

I’ve heard people use the term weeding to refer to the removal of books from library collections. In the collection development course I took in library school, I was taught to use the more formal terms deaccession and deaccessioning. The word withdrawal is also used. I agree that the word weeding isn’t suitable, not because it’s informal but because it suggests that the books being removed were never assets to the collection. I think pruning is better; when I decide to give away (or very occasionally throw away) some of my books, I’m removing things that no longer fit well enough to merit shelf space.

But suitability can be hard to define. Sometimes I keep books for reasons that aren’t easy to articulate. It’s often difficult to know when I’m ready to let go, or which books I might regret giving away. Consequently, there’s a lot of inertia in my book ownership. For months I’ve been contemplating going through a set of bookshelves that holds books more or less relevant to a blog I started in 2005. A couple of weeks ago, I finally tackled the job.

###

The story of the blog, the Thinking Meat Project, was reflected to some degree in the shelves. When I started the blog, I wanted to write, in very broad terms, about the human condition, about what it’s like to be an animal, vulnerable in the ways all living things are, while having a mind that’s aware of that vulnerability. I wanted to explore the ways we come to terms with that awareness. I thought that maybe art and religion were among the things that helped us deal with the loss and uncertainty inherent in our lives, and I planned to explore literature and poetry in addition to things more directly related to the study of the mind.

As it happened, Thinking Meat got pegged early on as a brain blog. That wasn’t quite how I’d envisioned it, but I was more interested in brain studies at the time than I am now. Because I have considerable experience with depression and anxiety, I was curious about what brain science can tell us about these conditions. In addition, as a result of my Catholic upbringing, I was still sorting out how to understand in a secular way concepts and emotions that are often associated with religion. I thought brain science had some interesting things to say about this subject.

Thinking Meat has been pretty much dormant for several years. While it was active, I wrote essays and book reviews that took an essentially humanist approach to the science of the brain. However, most of my posts were about current news in brain science, human prehistory, and social psychology. Those were the main topics because it was easy to find news stories and press releases on research in those fields. I also bought a fair number of books in these areas.

###

When I started sorting my TM books, I found that some of them had aged out of relevance and were fairly easy to let go. I didn’t need two books from the 1990s on the human genome, for example, or even one. I had several books on human origins by Louis and Richard Leakey, which might have been interesting to someone who knew the field of paleoanthropology well or was interested in its history. I saw no need to keep them. I suspect that my interest in human genetics and paleoanthropology might never have been strong enough to justify having these books on my shelves in the first place.

There were many books I’d simply grown away from. For instance, the books that focused on the brain and even on the brain and culture don’t interest me as much now, for various reasons. In the mid-2000s, I wrote many blog posts on neuroscience research that investigated human behavior and memory. I learned a fair amount, but I also realized the limitations of this work—in particular, the limitations of the association of brain regions with specific experiences, or of the evolutionary history of the brain—as a guide to what it means to be human. I was also much less interested in the quantification of human traits. Among the books I rejected were a 1952 book called The Scientific Study of Personality, by H. J. Eysenck, and a textbook on human intelligence.

I’d outgrown some books in a more positive sense; they’d served their purpose and were no longer needed. For example, I bought The Problem of the Soul, by philosopher Owen Flanagan, when I was trying to figure out how the concepts I’d learned from my conservative Catholic parents might work with my own (atheistic, non-supernatural) worldview. I had held onto the book because I remembered that it meant a lot to me when I first read it. I liked seeing it on the shelf and thought I might want to look at it again someday. But I realized that I can no longer articulate my reasons for wanting to read it; without noticing, I’d outgrown whatever problem I had with the soul. The book could go.

###

Still, I started to wonder, as the stacks of discards grew, whether I’d ever really wanted to read some of these books. Perhaps I’d wanted to be, or thought I should be, the kind of person who would enjoy them. Maybe what I’d outgrown in some cases was an idea of a possible future self. I’d stocked my shelves with an eye to someday carving out a niche in science writing, buying books that might provide good background reading or useful references.

I’d originally thought of TM as an outlet for energies and enthusiasms that weren’t tapped by my day job; I thought of it as an escape to more congenial work. But, like any human endeavor, it was shaped by external factors; it was a compromise between the desirable and the possible. To a degree I didn’t realize at the time, the books I bought were aspirational purchases, the belongings of a future self who never came into being. With hindsight, I wonder how plausible that potential self was. It seems clear now that for a while I lost track of the thing that originally motivated me to start writing: an urge to explore the felt experience of being a vulnerable animal.

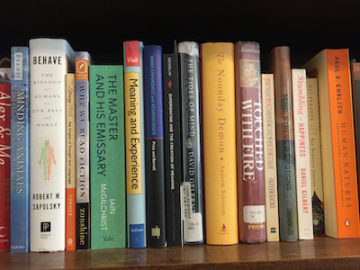

In the end, I cleared several shelves and donated around 75 books to the Friends of the Library Bookstore. The books that remain are much more focused on my original purpose. I thoroughly reorganized them and moved related books to the empty shelves. That set of bookshelves feels more alive than it has; a stagnant place has been re-energized. It’s sad to think of books as forming an obstacle, but I think to some extent that’s what happened, very slowly, without my noticing. Now I’ve cleared the blockage. It’s good to know that I’m still outgrowing things as I get closer to old age. I hope it means I’m still growing into things.

###

You can see more of my work at MaryHrovat.com.