by Ashutosh Jogalekar

This is the third in a series of posts about J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life and times. All the others can be found here.

In 1925, there was no better place to do experimental physics than Cambridge, England. The famed Cavendish Laboratory there has been created in 1874 by funds donated by a descendant of the eccentric scientist-millionaire Henry Cavendish. It had been led by James Clerk Maxwell and J. J. Thomson, both physicists of the first rank. In 1924, the booming voice of Ernest Rutherford reverberated in its hallways. During its heyday and even beyond, the Cavendish would boast a record of scientific accomplishments unequalled by any other single laboratory before or since; the current roster of Nobel Laureates associated with the institution stands at thirty. By the 1920s Rutherford was well on his way to becoming the greatest experimental physicist in history, having discovered the laws of radioactive transformation, the atomic nucleus and the first example of artificially induced nuclear reactions. His students, half a dozen Nobelists among them, would include Niels Bohr – one of the few theorists the string-and-sealing-wax Rutherford admired – and James Chadwick who discovered the neutron.

Robert Oppenheimer returned back to New York in 1925 after a vacation in New Mexico to disappointment. While he had been accepted into Christ College, Cambridge, as a graduate student, Rutherford had rejected his application to work in his laboratory in spite of – or perhaps because of – the recommendation letter from his undergraduate advisor, Percy Bridgman, that painted a lackluster portrait of Oppenheimer as an experimentalist. Instead it was recommended that Oppenheimer work with the physicist J. J. Thomson. Thomson, a Nobel Laureate, was known for his discovery of the electron, a feat he had accomplished in 1897; by 1925 he was well past his prime. Oppenheimer sailed for England in September.

Thomson recruited Oppenheimer to work on preparing thin films of beryllium in his laboratory, work that Robert found tedious and uninspiring. Already in November he was writing to his friend Francis Fergusson, “I am having a pretty bad time. The lab work is a terrible bore, and I am so bad at it that it is impossible to feel that I am learning anything…the lectures are vile.” Compounding his disappointment with his own experimental work was his jealousy at the success of Patrick Blackett, a brilliant experimentalist and a naval officer with movie-star good looks who was one of Oppenheimer’s mentors; Blackett was later to win a Nobel Prize for his work on analyzing particle collisions and founded the field of operations research during the Second World War. This kind of jealousy at the success of others, especially in comparison with his own failures, was perhaps unsurprising for a brilliant, ambitious, insecure young man who often expressed his worldview in dramatic terms. But in Oppenheimer it was particularly pronounced.

Apart from being immersed in the excitement of the world of Cambridge physics, another reason Robert had been looking forward to coming to England was to reconnect with Fergusson who was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford and plugged into the reaches of upper-class British society. Robert envied his friend’s connections and also envied the fact that, unlike his own non-existent love life, Fergusson already had a girlfriend named Frances Keeley. Ineptitude with experiment combined with his jealousy at Fergusson’s successful induction into both the English elite and a successful romantic relationship made Robert miserable. This misery startlingly manifested itself during a much-needed Christmas vacation in Paris where Robert and Francis met up. It was clear to Fergusson that his friend was depressed. In order to cheer him up Fergusson told Robert that he had proposed to his girlfriend and she had accepted. Suddenly without warning, Robert jumped at Francis and tried to strangle him. The rugged Fergusson easily fended Robert off, but the episode made it clear to him how deep-seated his friend’s psychological troubles were.

Another disturbing episode attesting to Oppenheimer’s psychological state of mind occurred when he was on a vacation in Corsica in the spring of 1926 with two other old Harvard friends, Jeffries Wyman and John Edsall. This vacation was otherwise uneventful and seemed salutary for Robert; the three friends walked in the scenic mountains, stayed at small inns, discussed Tolstoy and Dostoevsky (Robert: “Dostoevsky is superior to Tolstoy – he gets to the soul and torment of man.”) and joked about minor misunderstandings involving culture and language. Encapsulating his view of life, Robert proclaimed to Edsall and Wyman, “The kind of person I admire most would be one who becomes extraordinarily good at doing a lot of things but still maintains a tear-stained countenance.”

All seemed going well until one day when Robert suddenly announced that he had to return to Cambridge right away because he had left a poisoned apple on Patrick Blackett’s desk. In retrospect, it is very difficult to verify the truth of this episode. The public at large knows about it principally because it was stated by Malcolm Gladwell in his popular book “Outliers”. But the only account of it we have is from Fergusson, who himself got it from Oppenheimer. While it might be impossible to judge the veracity of the story, something clearly happened, because the authorities wrote to Robert’s parents who rushed all the way to Cambridge from New York to intervene.

Under threat of probation and possible expulsion, they and the authorities reached a compromise in which Robert would see a London psychiatrist. The psychiatrist diagnosed Robert as suffering from ‘dementia praecox’ (“precocious madness”), the then popular term for schizophrenia. Given our modern definition of the disorder, it seems safe to say that that was not what Oppenheimer was suffering from, and he seems to have realized it as such. One day, after a few sessions with the psychiatrist Fergusson found him pacing the streets of London, saying that he understood his own ailment better than the man did and that he would no longer see him. It was about this time that we see the glimpse of a recovery in Oppenheimer’s own mind, the slight opening of a window into a clarity that told him what his life’s real goal should be.

That recovery was a clear realization that his talents did not lie in experimental physics. Several factors might have been responsible for this realization. Oppenheimer might have remembered his learnings in the theoretical aspects of thermodynamics and other fields at Harvard, and at Cambridge he had already started making some forays into theoretical work, his quick mind filling in the gaps from his somewhat checkered education in these areas. He undoubtedly would have gotten wind of the exciting news coming from over the Continent about the latest developments in quantum mechanics. And at least one important episode might have guided his thoughts – an encounter with Niels Bohr who was visiting his old teacher Rutherford’s laboratory. Bohr asked Oppenheimer if his difficulties were mathematical or physical. While Oppenheimer did not have an answer, the famous Dane’s interest in his work made an impression. Then as later, Bohr radiated an avuncular warmth and kindness to him and a genuine interest in people’s problems that attracted young physicists to his tutelage and that must have assuaged Robert’s troubled soul. “At that point I forgot about beryllium and films and decided to try to learn the trade of being a theoretical physicist.”, he later remembered.

Late that spring, Oppenheimer met the physicist Max Born in Cambridge. Born who had never heard of the young American was impressed with both his interest in some of the same problems he was tackling as well as his broad facility with fields other than physics, a taste that Born himself shared. “Oppenheimer seemed to me, right from the beginning, a very gifted man.”, Born later said. After speaking with Oppenheimer, Born agreed to have him as his graduate student at the University of Göttingen. Armed with two papers he had already submitted on small but important improvements to quantum theory, Oppenheimer was about to enter the center of the world of theoretical physics.

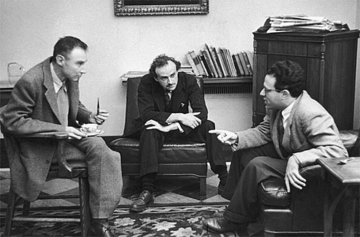

Max Born, born in 1882, was about the same age as Einstein and Bohr. He counted both among his close friends – it was in a letter to Born that Einstein uttered his famous phrase, “God does not play dice.” By the 1920s, Born had established the old University of Göttingen as the foremost center for theoretical physics, home to both his own group and that of James Franck, an experimental physicist who had won the Nobel Prize in 1925 and was on Oppenheimer’s Ph.D. committee (Born and Franck were later both forced to emigrate because of the Nazi purge of Jewish scientists). Over the years Born was to attract the finest young minds in the field, among them Werner Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli and Paul Dirac, all three of whom were among the founding fathers of quantum mechanics, the revolutionary theory of matter. Others like Einstein, Bohr and Arnold Sommerfeld from Munich visited often. Unlike Bohr who was as likely to lapse into philosophical soliloquies as discourses about physics, Born was a physicist’s physicist, steeped in rigorous mathematical training and entirely at home with working new theories out through hard calculations; he would win a belated Nobel Prize in 1954 for his interpretation of the quantum mechanical wave function. But along with being a great physicist, Born was also a great teacher. His mentorship of young men and women was without parallel. Along with Oppenheimer, Eugene Wigner, Maria Goeppert-Mayer, Max Delbrück and Victor Weisskopf were only four of the leading physicists of the 20th century who passed through his doors. His special talent was to guide gently and listen rather than issue orders in the style of a traditional blustery German professor. Discussions in his office could be accompanied by parallel discussions in his home.

Students could come to Born for either graduate study or on postdoctoral fellowships for a year or two. When Oppenheimer joined Born’s group, he immediately struck even his brilliant colleagues as unusual. For one thing, with his affluent family background he was much better off than the typical German students who were still struggling with the astronomical inflation that was the result of Germany’s defeat in the First World War. But more annoyingly, Oppenheimer came across as a know-all who seemingly jumped into any conversation in almost any language. Even more annoyingly, he was often right. The other students could only watch with indignation as Born stayed silent while Robert would suddenly jump up in a middle of a seminar, grab a piece of chalk and stride to the blackboard and interrupt whoever was speaking, saying, “This can be done in a much simpler way thus.” Born was known to make small mathematical mistakes in his complex calculations, often asking a junior colleague to check them. Once when Robert had checked his calculations he remarked to Born, “I couldn’t find any mistake – did you really do this alone?” Remarkably, Oppenheimer’s comment only increased Born’s esteem for him.

Born who was formidable in his command of physics was timid when it came to confronting his student. Soon matters came to a head. Maria Goeppert, one of Born’s most accomplished students, a former nanny to his children and one of the few female physicist of the 20th century to win a Nobel Prize, had her fellow students sign a petition. The petition said that unless Born silenced Oppenheimer’s frequent interruptions, his students would boycott his lectures. Born could not bring himself to face the American directly, so he used subterfuge. Once when Oppenheimer was in his office for a discussion, Born placed the petition visibly on his desk so that Oppenheimer was sure to see it. He excused himself for a few minutes under some pretext and stepped out of his office. When he came back, Robert’s face was white as a sheet. The interruptions stopped.

Robert’s larger than life personality, remarkable diversity of interests and rudeness continued to both fascinate and frustrate his colleagues. Apart from his physics studies, he still found time to read Chekhov, Fitzgerald and Zweig. His time at Göttingen coincided with a visit by Paul Dirac, the austere Cambridge theorist who is widely considered one of the greatest theoretical physicists in history. The taciturn Dirac and the voluble Oppenheimer improbably hit it off. Oppenheimer tried to get Dirac interested in poetry, leading Dirac to quip, “How can you work at both physics and poetry? In physics you want to say something that nobody knew before, in words which everyone can understand. In poetry it seems to be the opposite.” The two men retained a warm respect for each other, with Oppenheimer later frequently inviting Dirac to visit the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton which he directed after the war. Oppenheimer’s fluency with languages was also clear at Göttingen. Another set of friendships he sustained was with the Dutch physicists George Uhlenbeck and Sam Goudsmit who had made the seminal discovery of electron spin. “He was really a kind of oracle”, Uhlenbeck was to say. “He knew very much…he was very difficult to understand, but very quick.” Uhlenbeck and Goudsmit used to entertain each other in Göttingen’s cafes by quoting from Dante’s Divine Comedy. Oppenheimer was left out because he did not know Italian. For a few weeks the young American was absent from the cafes. When he emerged he could join the conversation, speaking perfectly adequate Italian (“Why do you waste time on such trash?”, was the single-minded Dirac’s predictable response).

At Göttingen Robert thrived both personally and professionally, breaking free from all the doubts and depression that had plagued him when he was doing experimental work. Göttingen was such a beehive of activity that more papers on quantum mechanics were published from there than from anywhere else, including Cambridge and Copenhagen; it was in Göttingen, working with Born, that the twenty-four-year-old Werner Heisenberg had published a paper essentially inventing quantum mechanics. During his fleeting tenure of just a year at the university, Oppenheimer published seven papers, an astonishing output for a twenty-three-year-old graduate student who just a year before had been floundering in experimental physics (the author of this piece remembers, with embarrassing nostalgia, how his own strenuous efforts in graduate school spread over six years led to six papers). Not surprisingly, the physics developed during that time, all done by men who were in their early 20s, came to be called “Knabenphysik”, the physics of the young. On the personal front, Oppenheimer formed lasting bonds with many of the leading physicists of the century who were visiting centers like Göttingen and Copenhagen, including Heisenberg, Pauli, Eugene Wigner and Enrico Fermi. Some were competitive bonds, some were friendly and some were both competitive and friendly. He also had a brief, platonic romantic attachment with a bright young physics student Charlotte Riefenstahl who was soon to marry Fritz Houtermans, a physicist with the same trappings of wealth and cosmopolitanism as Oppenheimer. But no serious romantic relationships intruded on Robert’s devotion to physics.

It was during his time with Born that Oppenheimer published what is, to students of physics and chemistry, his most famous and most cited paper. This paper refers to what is called the “Born-Oppenheimer approximation”. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation simplifies the mathematical treatment of complex molecules in quantum theory, opening the way to describing complex physics systems like semiconductors as well as chemical systems. To understand this approximation using a rough analogy, imagine a beehive surrounded by a cloud of buzzing bees. The light bees move very fast compared to the heavy beehive which might occasionally undulate because of the wind. If you were to now describe the combined system of the bees and the beehive, to a first approximation you could separate the motion of the two systems because of their very different patterns of movement. During any calculation describing the substantial movement of the buzzing bees in a single cycle, the beehive could be regarded as almost stationary and essentially ignored, simplifying the calculation. Similarly when you are describing a system with heavy nuclei surrounded by light electrons, as in a molecule of water for instance, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation allows you to ignore the movement of the nuclei and only take the electrons into account, simplifying the calculation. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is now a mainstay of calculations in many-body physics and quantum chemistry, taught to every graduate student in these fields.

It was clear by 1927 that Oppenheimer had come into his own as a promising theoretical physicist. While he was not in the first rank of theorists like Heisenberg and Dirac, he was certainly close. And he was American, ready to take the torch from the leading centers of Europe across the Atlantic. When his old teacher Edwin Kemble visited Göttingen to check up on his former student, he described Robert in a letter back home as being even more brilliant than what his Harvard professors had thought. In May 1927, Robert sat for his oral exam and passed it with excellent grades; one account has his committee member James Franck, a Nobel Laureate, saying, “I got out of there just in time. He was about to ask me questions.” Born found the parting hard. “It is all right for you to leave, but I cannot”, he told Oppenheimer. “You have left me with too much homework.”

While awarding him his degree, the university authorities found that Oppenheimer had failed to register formally as a student and threatened to withhold the degree. In response, Born came to Oppenheimer’s rescue and petitioned the authorities, telling the ministry of education that “economic circumstances render it impossible for Herr Oppenheimer to remain in Göttingen after the end of the summer term.” What the wealthy Oppenheimer who had a trust fund to his name must have thought of this obvious lie is not recorded. But there was no time to contemplate such minor infelicities. In just a year Oppenheimer had demonstrated that he had the brilliance and discipline to make theoretical physics his life’s work. It was time to take physics in America by storm.