A Conversation with Joan Giroux

by Andrea Scrima

Joan Giroux, born 1961 in Syracuse, New York, moved to the East Village in the early eighties to attend Parsons School of Design. After graduation, she began traveling back and forth between New York and Berlin, first as a guest student with Shinkichi Tajiri at the Hochschule der Künste, then to take part in a graduate program at the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY. With a focus on sculpture, Giroux moved from interactive objects and kinetic sculpture into installation, performance, social practice, and community engagement. She has shown internationally at venues including the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Weinberg/Newton Gallery, American Academy in Rome, Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Artists Space, BACA Downtown, and Künstlerhaus Hamburg, and has participated in international symposia for the arts and the environment in Korea, Japan, and Germany. She also shows her work in a number of public, alternative, and nontraditional venues, such as in the exhibition memory marks at the Hospice of Santa Barbara’s Leigh Block Gallery. Grants and awards include the Marie Walsh Sharpe Studio Residency, a Research Fellowship at the University of Michigan, and artist’s grants from Berlin’s Senate for Cultural Affairs and the Pollock Krasner Foundation, as well as residencies at the Squire Foundation and the MacDowell and Millay colonies. She teaches at Columbia College in Chicago.

Joan Giroux, born 1961 in Syracuse, New York, moved to the East Village in the early eighties to attend Parsons School of Design. After graduation, she began traveling back and forth between New York and Berlin, first as a guest student with Shinkichi Tajiri at the Hochschule der Künste, then to take part in a graduate program at the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY. With a focus on sculpture, Giroux moved from interactive objects and kinetic sculpture into installation, performance, social practice, and community engagement. She has shown internationally at venues including the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Weinberg/Newton Gallery, American Academy in Rome, Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Artists Space, BACA Downtown, and Künstlerhaus Hamburg, and has participated in international symposia for the arts and the environment in Korea, Japan, and Germany. She also shows her work in a number of public, alternative, and nontraditional venues, such as in the exhibition memory marks at the Hospice of Santa Barbara’s Leigh Block Gallery. Grants and awards include the Marie Walsh Sharpe Studio Residency, a Research Fellowship at the University of Michigan, and artist’s grants from Berlin’s Senate for Cultural Affairs and the Pollock Krasner Foundation, as well as residencies at the Squire Foundation and the MacDowell and Millay colonies. She teaches at Columbia College in Chicago.

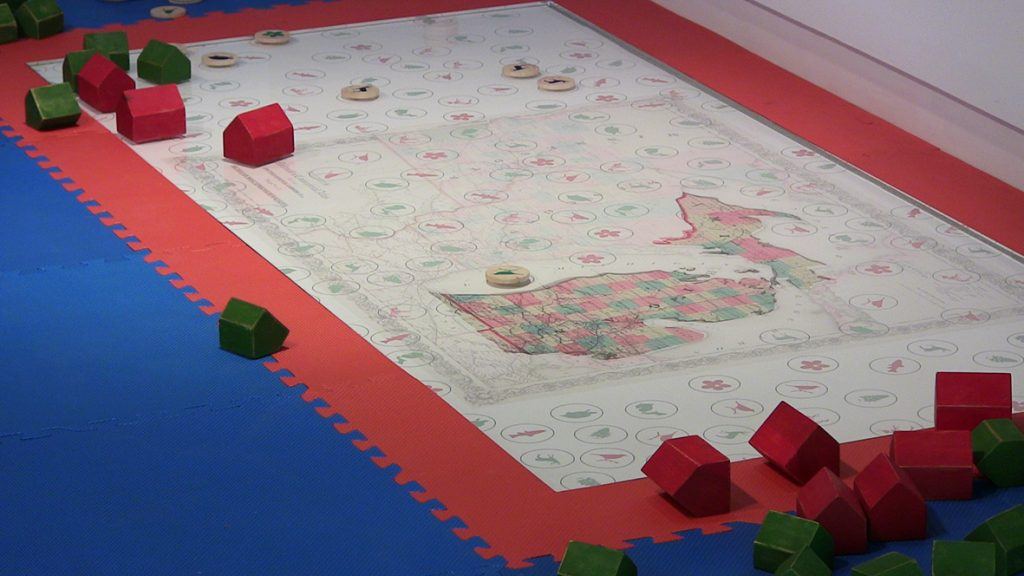

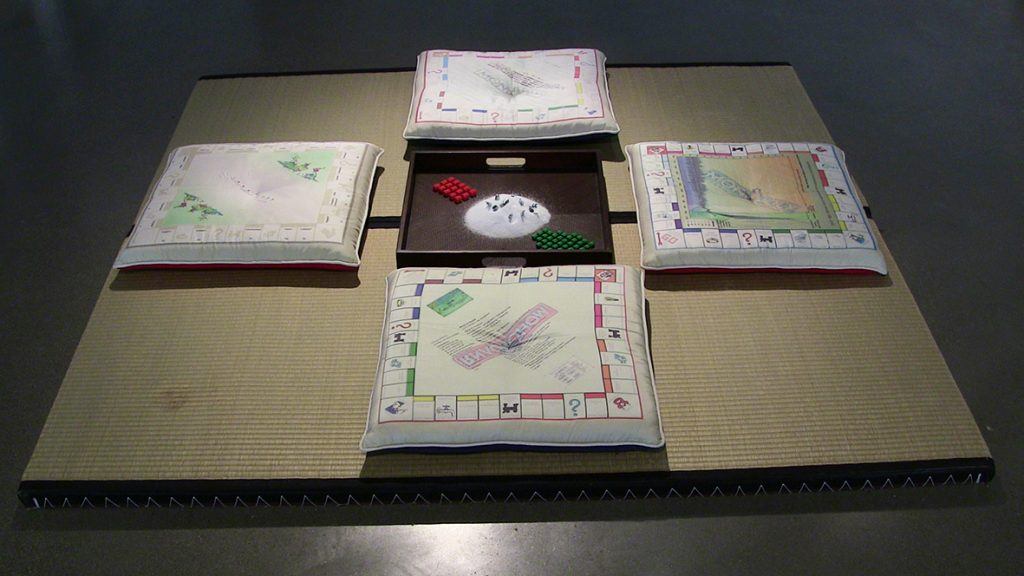

Andrea Scrima: Joan, a substantial part of your artistic practice is interwoven with socio-political and socio-economic concerns: I’m thinking in particular of the ongoing body of work titled eco monopolies, which examines land appropriation that feeds business interests at the cost of environmental sustainability, community, and quality of life. Could you talk a bit about the role of the artist as you see it today, and how you envisage your own work entering a larger public discourse? In other words, are we, as artists, equipped to change the world—and what role can activism play in art?

Joan Giroux: The eco monopolies series started out as a consideration of land development and its relationships to parks and green spaces, which isn’t a topic that’s high on many people’s minds. Since its nascent appearance in a forest in Yokohama, Japan, I’ve folded in the impacts of climate change and the relationship of economic policies to environmental justice. Insofar as art provokes us to consider alternate viewpoints, to imagine the world differently, or to expand our knowledge of cultures and attitudes other than our own, I do believe it can change the world, but it’s not a direct causal relationship. Though there are specific issues that repeatedly crop up in the work that can be interpreted and considered in overtly political terms, as in the eco monopolies body of work, I think of provocation in my work not as political activist provocation, but as a means for people to engage with ideas and experiences they might otherwise not be inclined to encounter. In the most recent iteration of that project, in an installation in the Commons at the MCA Chicago, I invited people—through a letterbox challenge developed in collaboration with the Chicago Park District—to venture outside their normal spheres and to visit different Chicago neighborhoods. In a highly segregated city, that individual act is a small gesture, but it opens windows of possibility. I see these windows opening up in my teaching practice, as well, where students—if you ask them enough questions, or confront them with enough unfamiliar territory—actually begin to teach themselves from their own experience.

A.S.: Some artists choose to take a more combative stance; I see your work as a nod of respect to this tradition, but in a category all its own.

J.G.: When we were students in the ’80s, and just out of school, beginning to find our voices, roles for artists were already shifting seismically. I remember being incredibly moved by Gran Fury’s Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do. That work was really a public service announcement to get people to sit up and pay attention to AIDS, and to consider the connections between the corporate greed of pharmaceutical companies and the indifference of politicians and the general public to the crisis. At the time I wished I had the wit and wherewithal to make such single-minded and clear work. But an activist stance, and even highly activist work, only makes sense for some artists; it’s not for everyone. Today, with so many directions in art—and types of artists making work—an incredible variety of roles exist; I don’t see any one role for the artist.

A.S.: How has your understanding of your own role changed throughout your career?

J.G.: Over the last three decades I’ve been making work, it’s evolved from a prior position of wanting to be a bit of a provocateur in the earlier work, to the outlook I have now, where I want the work and the experience of it to be more nuanced. I hope the work “speaks” to people who haven’t thought deeply about the subjects and experiences I’m broaching, some of which can be difficult to ponder.

To return to the question about whether artists (or art) are equipped to change the world: a few years ago, my colleague Meg Duguid asked me to participate in an exhibition she was planning titled Synapse. I remember finding the metaphor of a neuron powerful: the site where an impulse between nerve endings forms connections, and triggers cognitive responses, is a roadmap for how art at its best can work.

A.S.: What were some of the early experiences that most affected the evolution of your work?

J.G.: One big influence on my development as an artist was Joseph Beuys. I remember being almost smitten when I first learned about his theory of social sculpture. This idea that we all shape the world around us is at the core of how I was raised, with the understanding that we can all choose to actively participate (or not) in society. My parents were strongly civic- and community-minded, as were my siblings. My oldest brother Joe pivoted from going to college on an ROTC scholarship to involvement with the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society). As the youngest in this family of civically-minded folks in the ’60s, the women’s movement, anti-war protests, peace actions, civil rights, and the burgeoning of the environmental movement were just some of the forces triggering cognition for the young me. I was just turning nine after Nixon signed the executive order that gave rise to the EPA. And so it’s shocking where we’ve gotten to now with Citizens United and the erosion of environmental regulations that “burden” corporations.

A.S.: That reminds me of something Michael Chabon wrote in The Paris Review recently:

“Or, I wonder if it’s possible that I was wrong, that I’ve always been wrong, that art has no power at all over the world and its brutalities, over the minds that conceive them and the systems that institutionalize them. […] Maybe the world in its violent turning is too strong for art. Maybe art is a kind of winning streak, a hot hand at the table, articulating a vision of truth and possibility that, while real, simply cannot endure. Over time, the odds grind you down, and in the end the house always wins.”

J.G.: Yes, that’s exactly it. Art, the object itself, and the making of art, even being an artist, can feel at times like this incredible optimism that comes up against the realities of a world that at times has no patience for art, no space for art, or its conceits. Tilting at windmills is just one of the apt metaphors it brings to mind.

A.S.: In the face of such opposition, artists who have been making work for several decades often find themselves returning—sometimes intentionally, sometimes seemingly by chance—to sets of concerns from the earliest phases of their careers. What have been some of the recurrent themes in your oeuvre over the years?

J.G.: When I was quite young, four or five I think, I was convinced I would be a writer when I grew up. I would become a journalist, travel to war-torn countries, earn my bread and butter with adventure, and in the evenings write the great American novel, highlighting man’s inhumanity to man. During my teenage years, I read a lot of science fiction and fantasy, and it was also at this time that I was introduced to Kafka. As you noted earlier, socio-political structures and the dynamics of power relationships were part of the concerns and backstory driving the work and the thinking about the work. I think that’s why Kafka appealed to me: his writing seemed to comprise all the craziness of other realities and problems of power. Another thread that’s been present for a long time is an awareness of mortality and frailties, physical and nonphysical. That came about for a few reasons: my mother was a geriatric nurse, and after she retired, she volunteered as a hospice nurse. As a child I would sometimes accompany her to work, and so I was around elderly people who were essentially strangers, many of them in the active stages of dying. I came to know illness and death as a part of living. Then, as a teenager, I had an acute illness diagnosed as ulcerative colitis, considered psychosomatic at the time, but now understood to be an autoimmune disorder. In retrospect I think that experience at the age of sixteen formed a great deal of who I am today.

A.S.: I still remember some of your earlier works quite clearly, in which the game, for instance, was already a key trope. More often than not, the obvious playfulness of these pieces harbored an underlying subtext: the society as game, the economy as game, politics as game, the idea being less playful than systemic, in other words: a strict set of rules and strategies in which the dice are sometimes loaded and people really do lose.

J.G.: Yes, I’ve always been interested in the idea of fairness, and how even in the most apparent circumstances, where the rules of play are clearly spelled out, fairness can be so elusive. My dad used to say, “life isn’t fair” (and another, “people are no damned good”). I never really understood that, because he seemed to be an unfailingly fair person who also genuinely enjoyed the company of others. But then I read a book years ago, The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead, by David Callahan, and it spelled out in blunt terms how—due to fear, cynicism, and the gross inequities present in our economies and social systems—people take advantage of skewed systems to “get ahead.” It reads like a primer for the college cheating scandal recently come to light.

A.S.: And then there’s Lewis Hyde’s book Trickster Makes This World, which examines the creative and destructive forces in the trickster myth in light of contemporary art and the artist’s role.

J.G.: Yes, I’m familiar with the ideas from Hyde’s book, though I’ve never read it. I really should. I’ve thought about some of these roles for the artist and art as related to the idea of the truth teller. The Yes Men are a perfect example, with their role playing and creating entirely believable personas and the entire promotion, marketing, and web presence for these incredibly corrupt entities, exposing the venality of capitalism run amok. I found a postcard produced by them in my corner café in New York once, and wondered at the time about the satirical elements in their strategy and whether it works all the time. Now the model makes me think of disinformation campaigns, and question whether the culture jamming doesn’t at times reinforce those very elements it hopes to expose. . . It’s a complicated proposition.

Your bringing this up reminds me of a Lewis Hyde book I have read, The Gift, which for me resonates strongly with how I think art functions, a kind of sharing of energy and thought that moves out into the world and is carried forward in a gift economy governed by values of creativity and humanity rather than the bottom-line “fair” market value bestowed upon art as a commodity in neoliberal capitalism.

A.S.: This fits in with another prevailing motif throughout your oeuvre, the theme of caretaking. One of the earliest experiences you had with this involved your college friend Matthew, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1991. While I sometimes think that a good deal of work made by artists of our generation is somehow, at some very fundamental level, rooted in the experiences of the late 1970s and early 1980s, when people like Gordon Matta-Clark and Robert Smithson were active and important and the notion of commodification as we would come to know it in the arts was still on the horizon—just at the cusp, before the onset of the global art market—it was the arrival of AIDS and the sudden loss of young people close to you that seems to have been most formative.

J.G.: Well, growing up as the daughter of a geriatric nurse and hospice worker formed some of my earliest impressions. We had that Elizabeth Kübler-Ross book On Death and Dying at home, I can’t even remember much of the content, but I do remember thumbing through it. And my mom took care of many dying people even outside the institutions and volunteer work. The priest from our parish, my confirmation mother, and others I didn’t even know. That exposure, and understanding of the need for people to turn toward, rather than away from the dying, gave me the wherewithal to uproot my life in New York City and move to Germany after Matthew was diagnosed in ’85. At that time people weren’t faced with the question of how to live with AIDS; they were concerned with how long they would survive. Matthew lived longer than many, six years after his diagnosis. I knew then that the way to be the best support was to be there. AIDS as a pre-existing condition would have made it impossible for him to get insurance, and without insurance, no treatment would have been possible. He wasn’t coming back to the States. The experience of caring for him in those last months was so sharply human, and so embedded in trust. Several years ago, I trained in hospice myself, as a hospice volunteer, visiting people who were dying. I’d started a body of work, life review, after my mother died in 2008, unpacking her role as a caregiver in the home and in the institution, and later developed a series within this memorializing Matthew. That work has manifested in many forms: garments, prints, spoken word, staged performance. It’s still ongoing.

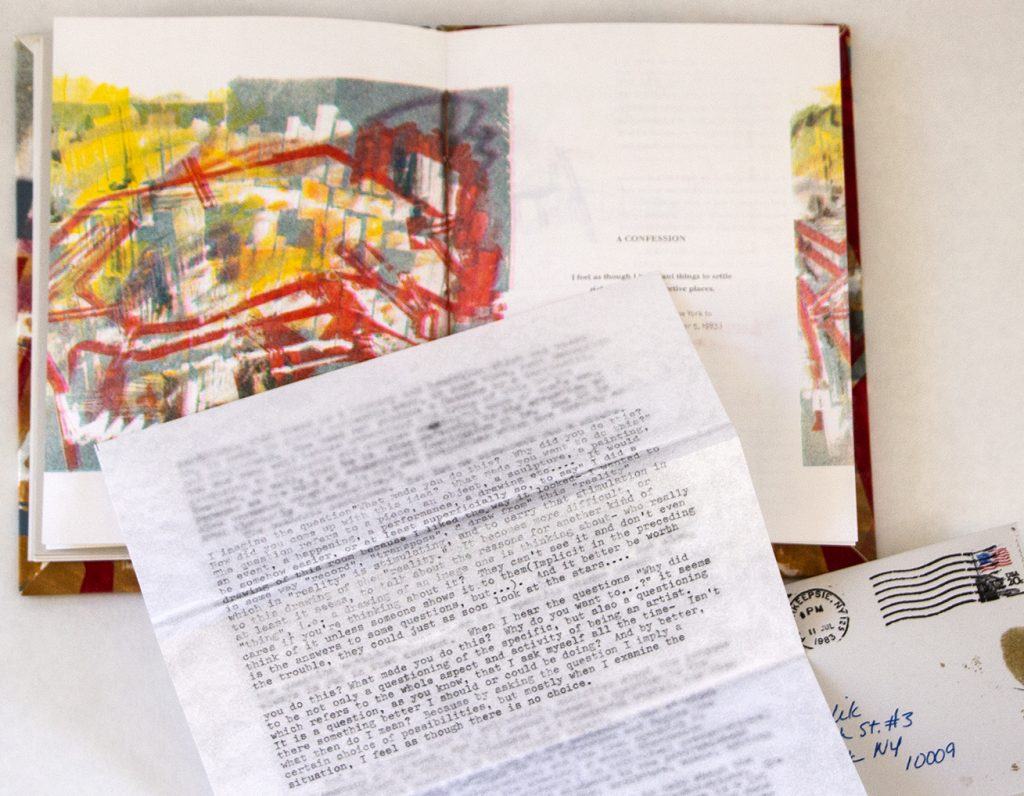

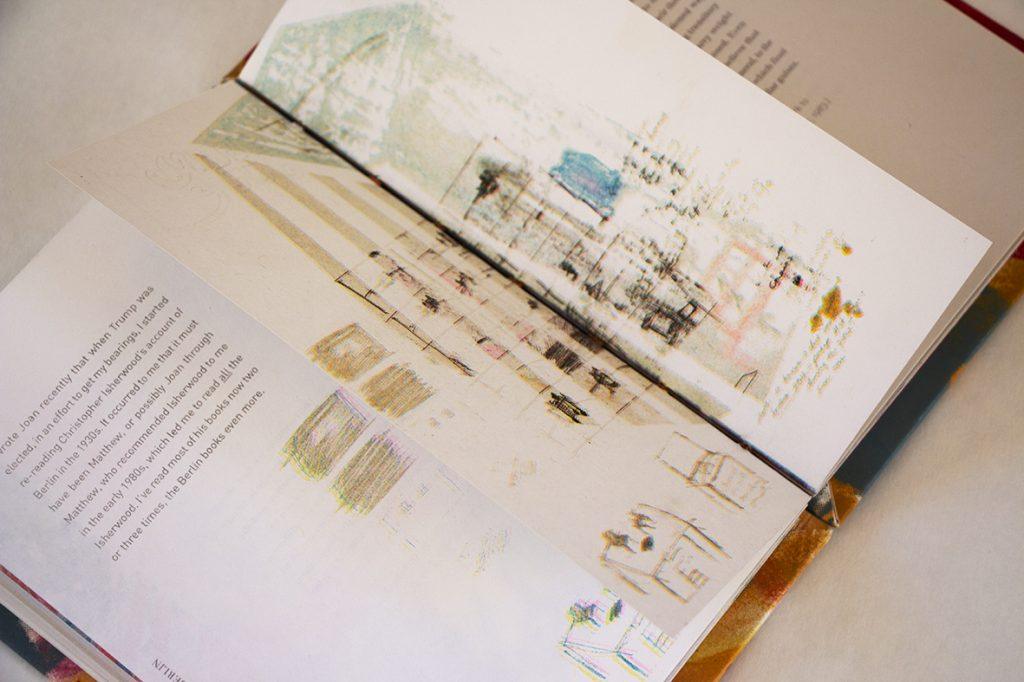

A.S.: Recently, you shared the text of a work-in-progress with me, an artist’s book titled marking a moment. It’s a collaboration with a writer friend, Steven Cheslik-DeMeyer, that draws on actual letters from the 1980s, when the two of you wrote back and forth to one another between Berlin, New York, points upstate, and the Midwest. I was very moved by some of what the young Joan had to say about artmaking, and I’d like to quote one section here, from a longer letter that’s reproduced in facsimile, in the form of an insert to the book:

“When I hear the questions ‘Why did you do this? What made you do this? Why do you want to…?’ it seems to be not only a questioning of the specific, but also a questioning which refers to the whole aspect and activity of being an artist. It is a question, as you know, that I ask myself all the time. Isn’t there something better I should or could be doing? And by better, what then do I mean?”

How did you ultimately resolve this nagging question, and when did you know that your art was the “something better” you were looking for?

J.G.: Honestly, I can’t say that I have resolved this nagging question, and that’s truly the right way to characterize it. I still find myself wondering whether I ought not to be doing something more directly in service to people. Right about now I wonder if I shouldn’t be volunteering for a political campaign. At the moment though, I’m at a residency at the Squire Foundation in Santa Barbara, where every day I get up and walk out the door of my bedroom, turn left, and walk into my studio. And that does feel like where I should be.

A.S.: Here is another quote from the same book, this one even more directly connected to your current work:

“So many people can and already have consolidated the two activities into one—the art, the politics—the activities of their thought and spirit combined in an impassioned way. But then most of them are creating transitory marks, temporal themes which carry weight no longer after the chapter is closed. Even given a specificity of situation, I believe that one must be able to extend to the general, to the pervasive, to the other pieces—that which float around in other places under similar guises.”

Where do you overlap with your younger artist self, and in what ways have you changed?

J.G.: How earnest that sounds. . . I can definitely say that—at this point in my life—I am not as earnest as all that. I’ve always taken things seriously, but now I do try (without a lot of success) to lighten up and roll with things. It goes back to what I said before, about shifting from a provocateur or rabble-rouser position, to thinking about and presenting things in a more nuanced way. A kind of a Benjamin Button development, maybe simply the result and process of getting older and less certain of my rightness, that state that visits us in our youth far too frequently.

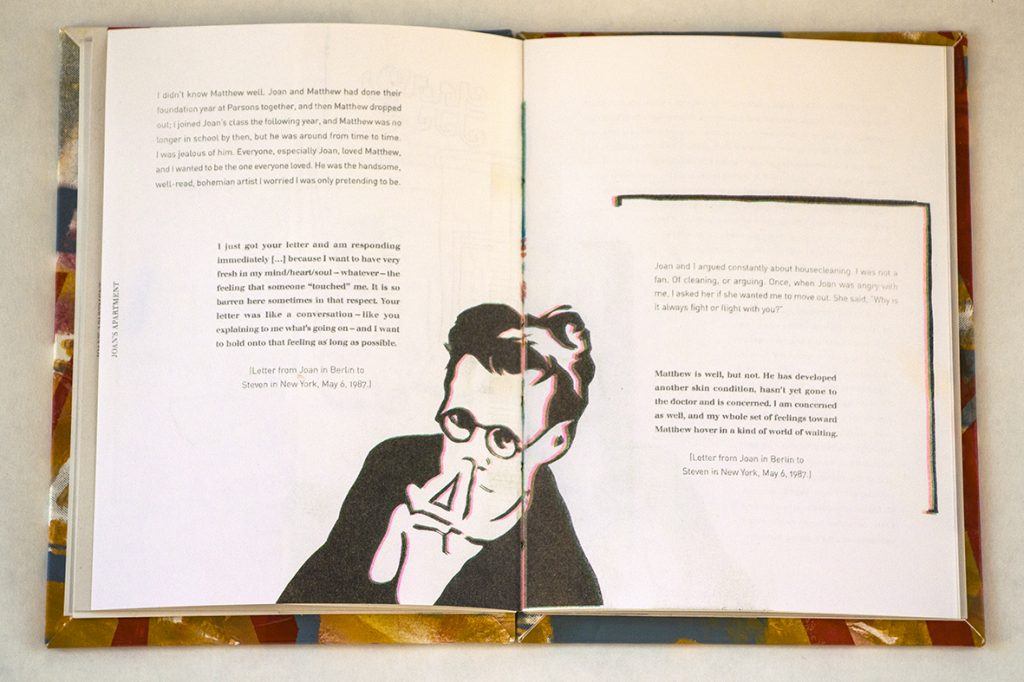

A.S.: Can you talk about some of the imagery in the book marking a moment, particularly the monoprints on the so-called “guards” separating the sections?

J.G.: During my training to be a hospice volunteer, and in subsequent reading, I’d encountered this concept of life review, which is understood in gerontology and psychology as a means through which individuals purposefully reflect upon and revisit life experiences in order to reconcile differences, achieve resolution, come to understandings and clarity, or accept states of uncertainty. I took life review as the overarching title to hold the work I was creating in reflection on my mother’s and Matthew’s lives—which by its nature included reflection on my own life both in relationship to them and as an individual. The book marking a moment is a life review for both Steven and myself: for him as the writer of a text originating today, and for me as I look back at letters I wrote and artwork I made decades ago.

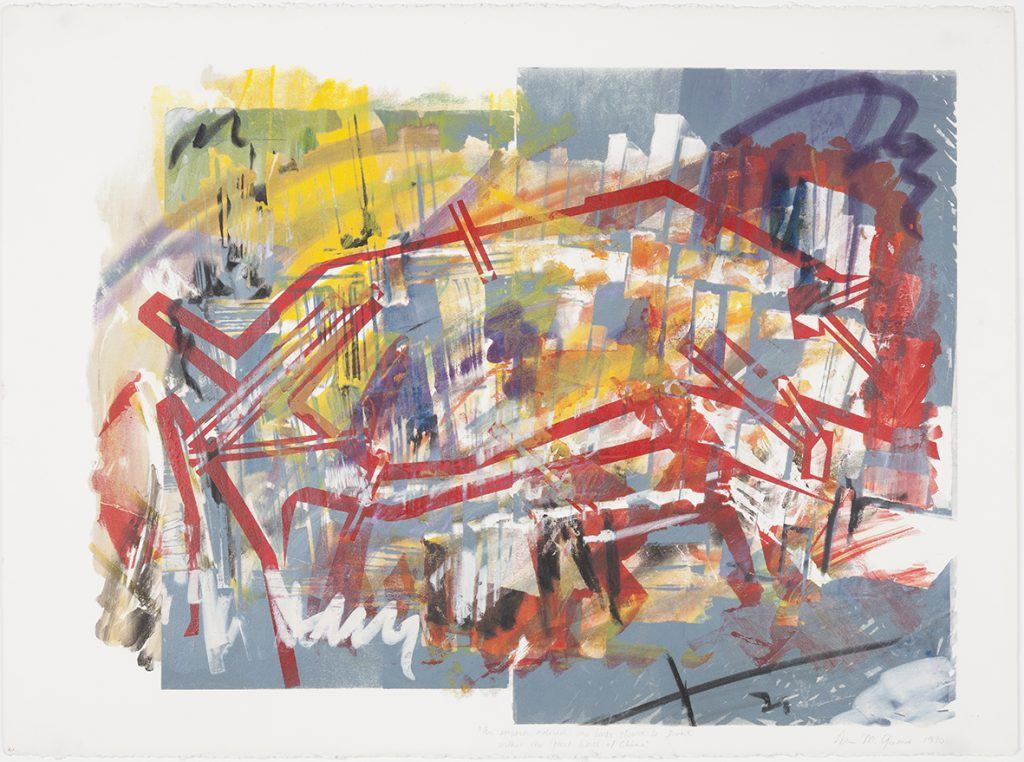

In 2017 a colleague had introduced me to curators at the University Club of Chicago while they were looking to commission sculpture for a space slated for renovation. That project got put on hold, but then the club invited me to exhibit work in another space where they show two-dimensional work. As my practice is generally object-, performance-, or spatially-based, I was at a loss. Then I recalled two series of prints I’d made in the ’80s and ’90s I’d always considered very strong, that had never seen the light of day.

The previous year I’d sat in on a basic silkscreen class to refresh my memory on those processes. As an undergrad I loved printmaking, especially silkscreen and lithography. Its immediacy and physicality attracted me to silkscreen, and, in a kind of opposition to that, the patience and concentration required to grind a litho stone was the incredibly calming pace I needed during those days of little sleep and continuous deadlines. As a form, printmaking seemed to me more related to sculpture than to painting or drawing, because, although the outcome was generally a two-dimensional object, the way to get there was, as with object-making, fraught with the harsh realities of physical laws.

Frequently as I was developing installation pieces, I would venture to the printshop to generate images and sketch out ideas. In some instances, the prints would become those permanent objects that could “document” the ephemeral performances and installations I was making. Looking ahead to December 2017, I decided to exhibit monoprints from two series: one, a series I’d made while developing the “pink chair installation” in 1984 for my undergraduate thesis defense, and another, a series of monoprints I’d made during graduate school to “document” the Ein Kaiser installation, from my first exhibition in Germany in 1988. I was also producing new monoprints related to the current work memorializing Matthew and engaging with illness, death, and dying as themes.

A.S.: How did the idea for an artist’s book come about?

J.G.: I thought it would be great to produce a small publication to accompany the show, which I called marking a moment. We’d recently gotten a risograph printer at the college, and I wanted to learn how to use this machine someone described to me as “what would happen if a mimeograph and a silkscreen had a baby.” I contacted Steven Cheslik-DeMeyer, a dear friend who’d been my roommate during art school and afterwards. He knew the early work really well, he was around during its making. We’d even collaborated on some drawings and ideas for performance pieces. When Matthew died, Steven was my roommate, working the graveyard shift as a legal proofreader, a “day” job he’d introduced me to in the late ’80s, and the means by which we both paid rent for many years. I remember getting the call at around 4:00 in the morning, about three weeks after I’d returned from that summer in Berlin, and my last time being there for, and with, Matthew. Steven’s cat Honey slipped into my room and snuggled up with me as I lay there crying until Steven came home.

Steven had known Matthew, and as a gay man he was also personally touched by AIDS, by what seemed like ceaseless instances of lives cut short in those days. Like Matthew, Steven had dropped out of Parsons after a couple of semesters, his creative trajectory shifting from visual art to music to theater to writing. I’d always respected his insights into art and my work in particular, and I thought Steven would be the perfect person from whom to commission a written piece tracing the connections between these projects spanning more than three decades. During the summer of 2017 I hired a photographer to document all the work in my flat files: drawings, paintings on paper, and prints, including the two series I would be exhibiting at the UCC, and the latest prints I had made in the last year.

A.S.: When I read Steven’s piece for the book, that entire time came back to me: the nihilism and the recklessness that seemed so normal to us back then, but also the earnestness, the innocence. We never knew how innocent we were. I’ve never been one to mythologize the ’80s or the East Village, but his writing invoked something in me that I’d forgotten, and it was very moving.

J.G.: Steven’s approach to writing the text was connected to his own current work, a musical based on his high school diaries. He’s been digging through his own past, reflecting on early life experiences, and so he pulled out all those letters he’d received from me in the ’80s. I can’t recall whether he and I talked about it at the time, but his process of poring through these papers he’d saved over the years presented an interesting parallel to the way I’d approached life review: sacrifice best what is not yours, a piece I developed for the 2015 QUEER, ILL + OKAY performance series. In that work the narrative arc is driven by images and texts from Matthew’s letters and postcards to me from the ’80s and ’90s, chronicling a decade of friendship and adventures together, with images of us two Americans in Berlin in that decade before the Wall fell.

A.S.: It’s a tricky thing to make work based on your own personal past, and even trickier to try this in collaboration.

J.G.: Yes, absolutely, but I think it’s been really successful. Steven approached the text by toggling between my voice in excerpts from letters to him, and his voice in recollections of that time and the linkages between it and the present. And so, like the life review QIO performance piece, marking a moment became another document of love and friendship, and a portrait of us young artists in New York City’s seedy East Village of the 1980s.

I decided to hire Madeline Noonan, a young designer recently graduated from Columbia College Chicago, to design the book. I shared all the documentation with her and gave her a broad brushstroke description of where certain pieces fit into my artistic development. I specifically pointed to images from the Ein Kaiser series that would be exhibited at the UCC. She chose these as the images at the front of each of three “chapters”: “Joan’s Apartment,” “Berlin,” and “A Confession,” and it was outtakes from this series that I cut up to make the book covers.

As 2017 was the year I turned 56, and seven signatures would generate 56 pages, the logic for what would ultimately become a limited edition of 56 books seemed unshakable. Just as with the two voices (mine and Steven’s, past and present), each signature alternates color: white with a gray guard, then gray with a white guard, then white with a gray guard again, and so on. Madeline took this idea of exchange with the voices and incorporated it visually into the guards by having each single signature’s guard image merge with the next on the leaf where both guards are visible. Each book, Coptic stitched with a handprinted cover, is incredibly tactile and visual.

A.S.: With the thirty-year anniversary coming up soon, I was recently commissioned to do an essay on the fall of the Berlin Wall; I spent a few days writing about the time, and that particular day, but then I felt something was missing—an immediacy, perhaps—and so I went back into my date books from 1989 and 1990 to fish for details. I’m familiar with working from journals, and drew heavily from my father’s for my last book, but confronting my own was frankly overwhelming. As we clock in the decades, the superimposition of all these different parts of our lives can feel surreal.

J.G.: Yes, when I was first becoming conscious of the forces that drive and inform the work, I recognized the surreal as part of it. I’ve always been fascinated by the tensions between what we see and think of as real, or factual, and another type of knowing that we have, where we just sense the truth of a thing or an experience. Now more than ever I accept a kind of absurdity connected to this, hearkening back to the incompleteness—and fracturing—of experience. Probably because of my earlier aspirations to be a writer, I’ve always looked to literature as a site of alternate possibilities. Worlds constructed in the imagination remind us what might be possible for our better selves. It makes me think of that conversation at King’s Cross where Harry Potter asks, “Is this real? Or has this been happening inside my head?” to which Dumbledore replies, “Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on Earth should that mean that it is not real?”

As I was wrapping up production for marking a moment, I recently revisited my undergraduate thesis. Your question—thinking about memory, looking back and looking forward—made me dig back to that. I opened the thesis with this quote from Nabokov’s Invitation to a Beheading which sums up quite nicely the surreality and the possibilities:

“But then perhaps I am misinterpreting these pictures […] But then perhaps I am misinterpreting […] But how can these ruminations help my anguish? […] the uncertainty is horrible—well, why don’t you tell me, do tell me—but no, you have me die anew every morning . . . On the other hand, were I to know, I could perform . . . a short work . . . a record of verified thoughts . . . Someday someone would read it and would suddenly feel just as if he had awakened for the first time in a strange country. What I mean to say is that I would make him suddenly burst into tears of joy, his eyes would melt, and, after he experiences this, the world will seem to him cleaner, fresher.”

The full text of the artist’s book marking a moment can be read here at Statorec.

Author’s note:

This conversation is part of a series I’ve done over the past year as a columnist for 3 Quarks Daily. I’ve talked to Madeleine LaRue about the Swiss writer Peter Bichsel; Liesl Schillinger about literature and politics; and Saskia Vogel about sex, pornography, and her debut novel Permission. There’s a conversation with Myriam Naumann that explores the connecting points between my book A Lesser Day and an installation I exhibited at the Berlin gallery Manière Noire, titled “The Ethnic Chinese Millionaire.” There are also conversations with the artists David Krippendorff, Alyssa DeLuccia, and others.

The series can be found in its entirety here.

My next 3Quarks conversation, which will appear on December 23, will be with the artists Eve Sussman and Simon Lee.