by David Greer

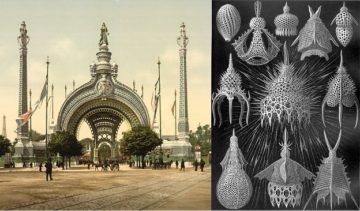

The 1900 Paris Exposition was a grand event, a world’s fair intended to honor the great achievements of the century just completed while heralding those of the century about to begin. In this spirit, architect René Binet designed a daring, futuristic entrance gate unlike anything ever seen before. It was as if he had had a prophetic vision, sixty years into the future, of a rocket launching into space. Binet’s concept, bizarre as it seemed, was far from imaginary. It was modelled after one of the most common creatures on Earth, though not one ever seen by anyone without a microscope. The animal that inspired the design of Binet’s Porte

Monumentale was a radiolarian, a form of zooplankton found in oceans everywhere.

The image of the radiolarian that so entranced Binet had been drawn by the German scientist Ernst Haeckel, a contemporary and admirer of Charles Darwin. Fascinated by the diversity of species and especially of the minute sea creatures seen through his microscope, Haeckel obsessively drew their forms in painstakingly detailed images. Reproduced in book form as Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms in Nature), Haeckel’s images caught the attention of architects and designers and became an inspiration for the Art Nouveau movement, of which Binet’s radiolarian gate was an early example.