I was startled for a moment before realizing that our neighbors had taken their child out of this suit before hanging it out to dry.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

I was startled for a moment before realizing that our neighbors had taken their child out of this suit before hanging it out to dry.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Ken MacVey

Do corporations have free will? Do they have legal and moral responsibility for their actions?

Do corporations have free will? Do they have legal and moral responsibility for their actions?

Many argue that legal and moral responsibility must rest on free will. If there is no free will there cannot be such a thing as legal or moral responsibility. But consider these two questions and their potential answers.

Do corporations have free will? Answer: No.

Do corporations have legal and moral responsibility for their actions? Answer: Yes.

Both answers intuitively sound plausible. On reflection these two answers, when taken together, logically imply legal or moral responsibility may not necessarily have to rest on free will. But maybe something is wrong with these answers. Maybe corporations do have free will of some sort. Or maybe any responsibilities corporations are said to have really rest on human stakeholders who do have free will. And if that is right, what are the implications for the legal and moral responsibility of corporations as their decisions become increasingly driven by AI instead of by people?

Under American law corporations are considered to be artificial persons. They are artificial in the sense that they are creatures of law. They are persons in the sense that they can be legal actors or agents. They can own property, enter contracts, sue and be sued, and file for bankruptcy. They have rights. They have First Amendment rights to free speech. They are entitled to compensation under the Fifth Amendment if their property is taken by eminent domain. They have legal obligations—such as paying taxes. Corporations can also commit crimes, even manslaughter. For example, Pacific Gas & Electric a few years ago pled guilty to 84 involuntary manslaughter charges stemming from a horrific fire in Northern California that PG&E caused. Corporations can have goals—sometimes they are recited in mission statements. They can take stands—such as endorsing by corporate resolution a ballot measure.

Historically corporations were not always legally treated as persons or as entities that could be charged criminally. Originally under the common law ( Anglo-American judicial precedents developed over hundreds of years) corporations could not have what is called mens rea, the “guilty mind” required for charging a crime. Nor could corporations commit an actus reus, or a wrongful physical act, also required for charging a crime. Judges ruled that corporations did not have minds so they could not have wrongful intent or a “guilty mind.” Judges would emphatically note that corporations do not have mouths to speak with, eyes to see with, hands to touch things and people with, thus they could not commit the “actus reus” or physical act required for being charged with a crime. As Supreme Court Chief Justice Marshall observed in 1819 in another context “a corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law.” Read more »

by Azadeh Amirsadri

I am in Del Mar having breakfast with two of my adult children who are telling me what sort of man I should date, and I wonder when did we switch roles. When did I stop being the one they were a little apprehensive about introducing a new person to and I became worried about their approval? Is it because I am too open with them? Am I too accepting of everything they do? Not that at their ages, I would want to control them or anything, but still. Is it because the last guy I dated was too enthusiastic about building an addition to my house to live in after a few weeks of our meeting, even though a few things were starting to not go well? Is it because in my euphoria of having found love again, I briefly looked at every red flag presented to me and just filed it away in a very far away part of my brain? Or is it because my daughter saw who he was when they first met when he told her that he is a silo and can move easily between different groups. Did she sense that he was all compartmentalizing and barriers, to my openness and connections?

I don’t stay with those questions long enough, because we are surrounded by the Lululemon crowd at this beautiful outdoor cafe. What Tom Wolfe called the Social X-Rays are brunching, and unlike my kids and me, they did not order extra pancakes on top of their regular orders. We seem to have to taste as much variety as possible, so every order has an extra side order. This crowd though is slightly less social x-ray and more face-fillers and pouty-lipped. A part of me is envious of their toned bodies and their casual Southern California relaxed vibe, workout outfits, and flip-flops, and another part of me is amused at the whole face thing. After our meal, which looked amazing but tasted quite bland, we went to the beach and soaked up all the sun we could for one day before two of us had to go back to the East Coast to attend a funeral.

Michael was my brother-in-law and became my brother-in-love. From the first time I met him in 1984, while his mother disapproved of her middle son’s relationship with me, and his sister warned her brother not to eat the food I made in case I added some sort of sorcery to it, Michael was all kindness and acceptance. He was amused, yet not surprised by his younger brother’s choice, and welcomed me and my children to his family without any questions. He was curious about me and my history, wanting to know more about how I grew up in Iran and France, my catholic school experience, my learning English days, and my religious and national holidays. He and his wife hosted us at their house in Pittsburgh and we all still remember the pizza they bought that was so rich, it was wrapped in newspaper to absorb the grease.

Michael was one of the most intelligent men I have known. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for the people of a nation to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with their Executive, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all Americans are created equal, that they are endowed by their Constitution with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, the Executive is chosen among Men and Women, deriving his or her just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Executive becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute a new Executive, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Executives lawfully appointed should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such an Executive, and to provide new Guards for their future security.–Such has been the patient sufferance of the people of these United States; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their present Executive.

The history of the present Executive of the United States is a history of repeated injuries, usurpations and monarchical tendencies, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Checks and Balances, Separation of Powers and Due Process, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has caused the destruction of the United States economy, which until recently was the Envy of the World, and consigned its Citizens to poverty and inflation.

He has eroded the goodwill of the United States among the Nations of the world, turning what was once a most admired country into the world’s pariah.

He has alienated our Friends and Allies and embraced other Tyrants and autocrats. Read more »

by Jonathan Kujawa

The humble 2. It’s not big, like the Brobdingnagian numbers. It’s not nothing, like zero. It’s not the first something, like one. It’s hard to imagine much can be said about the unremarkable two.

Of course, Covid gave us a newfound appreciation for the power of exponential doubling. If you know of a novel disease and have 3 cases yesterday, 6 cases today, and are told to expect 12 cases tomorrow, it is quite something to predict close to zero new cases by April. But I’m just a simple mathematician who finds pulling random numbers from my rear end uncomfortable.

A happier, if apocryphal, tale is about the invention of chess. The story goes back to at least the 11th century: a clever courtier invents chess and presents it to their king. The king so loves the new game that he offers to give the courtier whatever they request. The courtier says that they’d like one piece of wheat for the first square of the chessboard, another two pieces for the second square, another four pieces for the third square, another 8 pieces for the fourth square, and so on for the 64 squares of an 8 x 8 chessboard.

18,446,744,073,709,551,615

grains of wheat for the courtier. That seems like a lot to count and you might rather weigh it out. Even then, it’ll be some work. After all, we’re talking about something like 18,446,744,000 metric tons.

A riddle loved and hated by students when they first learn about the prime numbers is: “What is the oddest prime?”. Sure to generate groans, the answer, of course, is two. Why the oddest? Being the only even prime makes two the black sheep among the primes.

On a questionably more serious note, the largest prime numbers are found using powers of two. As we talked about here at 3QD, last October the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search announced that

2136279841-1

is the largest prime number known to humankind. It has 41,024,320 digits. Printing it out would take an 8,000 page book if you wanted to carry it around with you. Read more »

Stephanie Morisette. Hybrid Drone/Bird, 2024.

Stephanie Morisette. Hybrid Drone/Bird, 2024.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

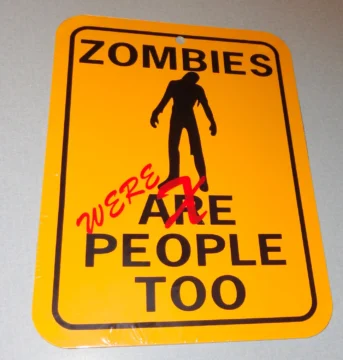

by Tim Sommers

Or, rather, the very real threat to Physicalism posed by Philosophical Zombies.

On the one hand, there are the Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, Shaun of the Dead, Walking Dead, zombies, which are rotting, but animated, corpses that devour human flesh and can only be stopped by destroying their brains. They pose a physical threat.

On the other hand, there are philosophical zombies that pose a much deeper, more unsettling threat to physicalism itself. Philosophical zombies look and act just as we do, but they have no internal, phenomenal mental life. Like celebrity influencers.

Physicalism is, roughly, the view that everything real is either physical or reducible to something that is physical. Arguably, it’s the philosophical view that undergirds modern science. The physicalist slogan that I grew up with was “all concrete particulars are physical.”

That is, there are abstract objects (like numbers or sets) as well as generalizations about concrete objects (say, about horses having four legs). And these are in some attenuated sense real. But any given example of a nonabstract object will be physical. When it comes to the human mind, physicalism does not have to mean that “redness” or “pain” is some particular unitary brain state, but rather that every time you perceive something as red your perception is caused, and constituted, by you being in some particular brain state. That’s called token physicalism or nonreductive materialism.

There are plenty of objections to this view. In a recent 3 Quarks Daily article Katalin Balog discussed the problem of causality. Since most philosophers accept the “causal closure of the physical” – every physical event has a physical cause, so nothing nonphysical can cause something in the physical world – mental events like pain or redness are, at best, epiphenomenal*. Even if they exist, in other words, they are caused by physical events or processes, but they can’t cause anything. Yet, the causal objection goes, isn’t it the fact that I see a light exemplifying the phenomenal property of redness (as philosophers used to say) that causes me to stop?

I want to discuss a different argument, however. The one about zombies, which Balog also mentions in passing. Rather, than being causal this is an objection to physicalism from phenomenal consciousness. Read more »

by Ed Simon

Alternating with my close reading column, every even numbered month will feature some of the novels that I’ve most recently read, including upcoming titles.

There was a meme that circulated a few years back amongst the tweedier of the interwebs which roughly claimed that when it came to literature, great French novels are about love, the Russians focus on existence, and Americans are concerned with money. Like most jokes in that vein, the observation is more funny than perceptive, though it’s not really much of either. Regardless, there is some truth to the quip, one worth considering no more so than right now, the month that sees the centennial of that greatest American novel of upward mobility and conspicuous consumption F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. “Let me tell you about the very rich,” promises Fitzgerald through his narrator Nick Carraway, they “are different from you and me.” From Edith Wharton’s The Age of Mirth to Brett Easton Ellis’ Less Than Zero, American literature has long focused on money, even if it’s under the guise of “freedom” (the former being a prerequisite for the later anyhow). Whether or not that’s the intrinsic, essential, integral deciding difference and definition for American letters is too sweeping a claim to make, for certainly there are Frenchmen not concerned with love and Russians of a lighter disposition, but for the four new American novels I read this month, and the single English novel concerned with class – which is just money baked for four centuries and dressed in a tuxedo and top hat – money was certainly the major topic of concern.

Sara Sligar’s deft and entertaining new novel Vantage Point, published this past January, imagines inherited wealth as the wages of a historic curse, returning to that earliest and most American of genres in the gothic. Vantage Point’s narrative is loosely based on Charles Brockden Brown’s 1798 Wieland; or, The Transformation: An American Tale, arguably the first example of the American novel and one that you’re unlikely to ever heard of unless you’re a specialist, for the simple reason that it’s more interesting than it is good. In Brockden Brown’s original, the titular Wielands are Pennsylvania gentry, cursed by the memory of their father spontaneously combusting in his library overlooking the Schuylkill as a result of his alchemical experiments, only a generation latter to be taken in by the nefarious machinations of a biloquist named Carwin. Read more »

Don’t tell me the earth’s a sphere

and the sun’s kiss amounts to half-day

terminal bliss with a dark end,

or that seasons have to do with angles,

mystics have to do with angels,

and lovers are about orbiting passions,

that pulse like binary stars across

light years and come in telescopes

Don’t tell me the wind’s a metaphor

for a longing to fill vacuums that

sometimes spit typhoons

or that cardinals seen

in the high reaches of cherry trees

are no more sublime than worms

who burrow among turnip roots

for a living

Don’t tell me the chance of being

is equal to the odds of not being

——tell me something I don’t know

Tell me how to weave

tomorrow into yesterday

without tangling, without

strangling today

Jim Culleny

from Odder Still

Lena’s Basement Press, 2015

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Daniel Shotkin

Last summer, I wrote an article about Affirmative Action, college admissions, and what it meant for me as a high school senior. At the time, I’d just begun the arduous process of applying to colleges, and I was frustrated. Getting into a ‘top’ college had been my dream for the past four years, but the admissions process I had to go through to achieve said dream seemed to be purposefully designed to be as opaque as possible. So, while many of my friends developed fixations on ‘dream schools,’ I adopted an ultra-cynical view on the whole ordeal—I’d play the admissions game, but I’d expect nothing more than a loss.

But that view has been slightly complicated by a recent development. Last week, I was accepted to Harvard.

As streams of digital confetti floated down my refreshed application portal, I felt like I’d won the lottery. No, it couldn’t be true. Harvard’s acceptance rate sits at a measly 3.6%, meaning to get in, I’d have to squeeze past 50,000 chess prodigies, olympiad winners, and violin virtuosos. Add the fact that my suburban New Jersey public school had only had one accepted student in the past ten years, and such a feat was impossible. But somehow, there I was, mouth agape, mom hollering, and acceptance letter in hand.

So what now? Was my pessimism an overreaction?

The irony of my situation isn’t lost on me. In discussions with friends, family, and teachers, I’d been the Ivy League’s biggest critic. But I’d also worked hard to craft an application that appealed to their admissions system. How do I reconcile these two truths? To answer that, we first need to understand why a certain Boston-area liberal arts college has such a hold on high-achieving high schoolers. Read more »

by Scott Samuelson

But lo! men have become the tools of their tools. —Henry David Thoreau

The other day I was talking to some university students, and I asked them to what extent AI could be used to do their required coursework. Would it be possible for ChatGPT to graduate from their university? One of them piped up, “I’m pretty sure ChatGPT has already graduated from our university!” All chuckled darkly in agreement. It was disturbing.

Workers experience anxiety about the extent to which AI will make their jobs yet more precarious. Because students are relentlessly conditioned by our culture to see their education as a pathway to a job, they’re suffering an acute case of this anxiety. Are they taking on debt for jobs that won’t even exist by the time they graduate? Even if their chosen profession does hold on, will the knowledge and skills they’ve been required to learn be the exact chunk of the job that gets offloaded onto AI? Are they being asked to do tasks that AI can do so that they can be replaced by AI?

This crisis presents an opportunity to defend and even advance liberal arts education. It’s increasingly obvious to those who give any thought to the matter that students need to learn to think for themselves, not just jump through hoops that AI can jump through faster and better than they can. The trick is convincing administrators, parents, and students that the best way of getting an education in independent and creative thinking is through the study of robust subjects like literature, math, science, history, and philosophy.

But if we really face up to the implications of this crisis, I think that we need to do more than advocate for the value of the liberal arts as they now stand. The liberal arts have traditionally been what help us to think for ourselves rather than be tools of the powerful. We need a refreshed conception of the liberal arts to keep us from being tools of our tools. (More precisely, we need an education that keeps us from being tools of the people who control our tools even as they too are controlled by the tools.) To put the matter positively, we need an education for ardor and empowerment in thinking, making, and doing. Read more »

by Abigail Tulenko

On March 25th, Tufts University PhD student and Fulbright scholar Rümeysa Öztürk was forcibly detained and taken into ICE custody. Though the young woman posed no physical threat, she was surrounded and restrained by no less than six plain-clothed officers. Video footage shows that badges were not presented until after Rümeysa was restrained. No charges have been filed against her, and she was not afforded the right to due process. As they arrested her, the officers covered their faces with masks. In the Nation, Kaveh Akbar writes that “they looked suddenly…like they needed to hide from God their ghoulish glee at disappearing a…student who, it was later reported, was walking to break Ramadan fast with her friends.”

Like the masks, the words we use for this incident often function to obscure. Take the word “detained.” Rümeysa isn’t being detained in any sense of the word as we use it in non-legal contexts. It’s not as though the officers have held her up or made her late to her dinner. For over 24 hours, her family and friends were not able to contact her or informed of her whereabouts. Rümeysa’s belongings were taken from her, she was barred from communication, and disappeared to Louisiana- over a thousand miles from the city she lives in.

Take the word “custody,” which implies care, protection, guardianship. Gardeners are custodians of their plot, parents have custody over their children. To call the violence of the state “custody” is a profound perversion of the word’s historical meaning. The violence Rümeysa experienced and continues to experience is the opposite of care and protection.

Take the “detention center.” This too, glosses over the reality of her situation. “Detention” evokes a stale classroom after-school. In actuality, as a special report from the American Immigration Center argues, the US immigration detention center is in many ways virtually “indistinguishable from criminal incarceration” from the layouts of its facilities, to its systems of punishment and surveillance.

I begin with this analysis of words because Rümeysa herself holds language dear. Her academic work reveals a profound attention to the manner in which our concepts have real consequences in the world, shaping and demarking the realm of political and personal possibility. As we can see in the news coverage of Rümeysa’s abduction, the language we use to refer to state violence covertly shapes our imagination of its nature. Words like “custody” and “detention” obscure the reality of what Rümeysa experienced. But Rümeysa’s work shows us how words can also be liberatory- revealing not only what is, but what can one day be.

Like Rümeysa, I am a third year PhD student in the greater Boston area. Read more »

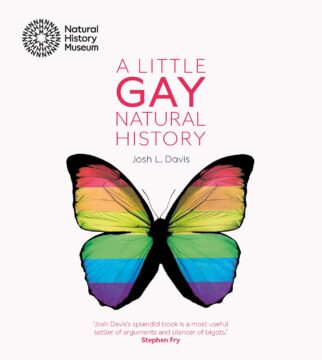

by Adele A.Wilby

In his inaugural speech on 20 January 2025, Donald Trump jumped into the fray on the contentious issues of gender identity and sex when he announced that his administration would recognise “only two genders – male and female”. At this point there is no conceptual clarity on his understanding of the contested issues of ‘gender’ and ‘male and female’, but we do not have to wait too long before he clarifies his position. His executive order, ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremists and Restoring Biological Truth to Federal Government’ signed by him soon after the official formalities of his inauguration were completed, sets out the official working definitions to be implemented under his administration.

In his inaugural speech on 20 January 2025, Donald Trump jumped into the fray on the contentious issues of gender identity and sex when he announced that his administration would recognise “only two genders – male and female”. At this point there is no conceptual clarity on his understanding of the contested issues of ‘gender’ and ‘male and female’, but we do not have to wait too long before he clarifies his position. His executive order, ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremists and Restoring Biological Truth to Federal Government’ signed by him soon after the official formalities of his inauguration were completed, sets out the official working definitions to be implemented under his administration.

Trump issuing orders for ‘defending women’ would have undoubtedly raised the hackles of many and sniggers from even a greater number of women who are only too aware of his derogatory comments about women and his questionable and contested long history of relationships with them, but that is not the issue here. What is at issue is the clarification the executive order expounds on his conceptual understanding of sex when it says, “Sex’ shall refer to an individual’s immutable biological classification as either male or female. “Sex” is not a synonym for and does not include the concept of gender identity’. This delinking of sex and gender allows space for gender diversity, but that is a short-lived optimism. The executive order continues to elaborate the gender essentialist view that ‘women are biologically female, and men are biologically male’. In other words, he denies the fluidity of gender identity and the diversity of cultural constructions of ‘man’ and ‘woman’ and posits gender as inextricably linked to biology.

The gender concepts of ‘woman’ and ‘man’ remain unclarified in the text, but by grounding these identities in biology, the executive order, in one sweep, rejects the cultural constructions of gender and delegitimises the identity of transgender persons or any other gender identity an individual might feel and experience themselves to be. Read more »

by Steve Szilagyi

Edgar Watson (E.W.) Howe (1853–1937) was a small-town newspaperman who became nationally known for his plainspoken wit, tart epigrams, and relentless skepticism. “I must make everything so simple that people will see the truth,” he once said. His sayings—blunt, dry, and often astringent—were the fruit of decades spent editorializing in the Atchison (Kansas) Daily Globe and later in his one-man magazine, E.W. Howe’s Monthly.

How famous was he? Howe’s Daily Globe had subscribers not only across the U.S. but in thirty countries. His columns were praised by the likes of Heywood Broun and Mark Van Doren—who called them “the best in the language.” H.L. Mencken became a devoted admirer. At the 1915 San Francisco Exposition, his sayings were spelled out in electric lights. A 1927 testimonial dinner in New York drew a crowd of luminaries: Bernard Baruch, Ring Lardner, Walter Winchell, Rube Goldberg, and John Philip Sousa.

Though Howe also wrote novels, memoirs, and travel books, his enduring reputation rests on the sharpness of his aphorisms. These were collected in volumes like Country Town Sayings, Ventures in Common Sense, and Sinners Sermons. A few examples:

His personal story was every bit as compelling as his quips. Howe was the son of a hellfire Methodist preacher who forbade toys, candy, or any whiff of fun. The defining calamity of his youth came when he was eleven: his father abandoned the family and ran off with a woman from church. Howe became a tramp printer, working odd jobs and roaming the West. Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

The popular TV horror-drama The Walking Dead followed an evolving cast of characters in the aftermath of a zombie apocalypse. The comic on which it was based called it “a continuing tale of survival.” And that it is. Time after time, the survivors settle into some particular situation, only to be met by some new threat that upends their safety and sends them out into a dangerous world time and again. The real danger is other people, not the zombies who become a manageable threat. By the end of the series (SPOILER ALERT) some of the original core group manage to find a community large enough to ensure some peace and normalcy, even as the apocalypse grinds on outside their gates. Many read the show/comic as a warning about humanities’ propensity for unbridled violence in the absence of civilization. Without the threat of the state monopoly on violence, most humans will turn to some sort of violent primitivism, goes the argument. But different messages can come from the show and comic.

Rather than being evidence of man’s Hobbsian state of nature, I’d argue that it’s evidence of what happens when the structures of neo-liberalism begin to crack, but not the underlying ideology of neo-liberal individualism. This precisely describes what we’re seeing under the second Trump administration and in other authoritarian regimes around the world. Since the emergence of capitalist modernity and especially in the wake of two global wars, the world has been organized into nation-states in the international rules-based order. Authoritarians of the postmodern right tell us that these systems are the problem, and destroying them will fix it. But they seek to tear apart systems in order to benefit themselves, not to replace it with anything beneficial for humanity. But can these systems now under attack be employed for more democratic ends? I’d argue yes, they can. Systems are tools and tools can be used in multiple ways, for good or ill. We can turn these systems for good.

The nation-state is the building block of the modern international rules-based order. Modern nationalism, a modern understanding of political belonging, was deployed during the 19th century against eastern empires that western empires sought to destabilize. The Ottoman Empire was one such target of this process of destabilization. Nationalist activist from the Balkans, often educated in Paris or London, brought back new-fangled ideas about an immortal national body being suppressed and abused by an illegitimate imperial (orientalist) power.1 Such ideological machinations would not just disrupt the peace of the Ottomans, but would soon boomerang back on the French and British empires, such as with the Irish rebellion against British colonialism or Vietnamese and Algerian uprisings against the French, among others. By the time the Second World War ended, a war which some have described as imperial rule coming home to roost, a new system was emerging that favored the nation-state over empires, the US and Soviet-led interstate system. Read more »

by TJ Price

My first job, like so many others before me, was in customer service at a grocery store. I started as a bagger, positioned at the tailboard of a register, waiting for the cashier to slide down the items the customer chose from the store at large, though eventually I moved up to manning the register myself. I learned the PLUs for various items of produce, and even in the intervening twenty-odd years, none of them have changed. It’s stil 4011 for bananas, 4065 for green bell peppers, 4048 for limes, 4664 for tomatoes on the vine. Organic? Toss a 9 on the front of the number, and the price magically raises—but so, too, ostensibly, does the quality of the item.

I remember with great clarity these days, standing behind the belt, greeting each shopper, sending them on their way, besieged by the inane requests and tyrannical behavior of managers. I remember one day in particular, when an elderly woman was checking out at the register next to mine, manned by a tough-as-nails woman named Deb with iron-gray hair and no-nonsense attitude that nonetheless often bore the thin twist of an acidic smile. I liked Deb—she didn’t take shit from anyone, and the customers appreciated her briny, forthright manner too, as well as her brisk pace.

On this day in particular, a man approached the line from behind, licking his lips and looking nervously around. He wore a pair of ratty sweatpants and a long coat, and looked disheveled, but otherwise non-threatening. He greeted Deb, and then the elderly woman in front of him. I didn’t hear how he got her attention—perhaps a dry, “Excuse me, ma’am,”—but the next thing I knew, he’d pulled down the front of his sweatpants and exposed himself to the woman. She gasped in shock, reeling backward. I only caught the briefest glimpse, and a similar horror froze me in place—but Deb didn’t even blink. With one hand, she seized one of the plastic separators from its sill next to the belt and, in one swift motion, smacked the man right in his … let’s call it his “display area.”

“Put that away, you pervert!” Deb shouted over his howl of pain—like a flash, the man was gone in a cartoonish tousle of coat and a shocked, blinking expression. I’ll always remember the look on the elderly woman’s face—a confused mix of horror and admiration—and yet, after her transaction, she hurried out of the store without so much as a thank you to Deb. Read more »

by Mark Harvey

Geography has made us neighbors. History has made us friends. Economics has made us partners, and necessity has made us allies. Those whom God has so joined together, let no man put asunder. —John F. Kennedy addressing the Canadian Parliament, 1961

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.

I’ve always loved Canada. My first visit there was as an eleven-year old when my mother sent me up to Vancouver to live with a friend’s family for the summer. Vancouver is such a jewel of a city and Canadians are such nice people that even at that age I was appreciative of our northern neighbor.

Getting your arms around the Canadian character is not easy. There are a few stereotypes, one of them being that Canadians are polite. Guess what: in general, they are polite. But I have a sense that Canadians have two very different sides to their character, one being the pleasant law-abiding citizen, and the other represented by their raging hockey fans or their certifiably crazy world cup ski racers, once called The Crazy Canucks. To their credit, Canadians keep these two parts of their personalities in separate vaults and usually don’t mix the two. But have no doubt: behind the good manners and friendly dispositions, Canadians have a fierce side and iron will not to be trifled with. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

No, this column is not a retrospective of What’s Left? How Liberals Lost Their Way, a book by the British journalist Nick Cohen, even though the title of that forgettable volume is apposite here (I’ll come back to this below). Rather, my title is a reference to a conference that took place in Torino in 1992 under the title of What is Left?, though the post itself is meant as a revisit to Norberto Bobbio’s Destra e Sinistra (Left and Right, in its English edition), a short book from 1994 first thought up at the just-mentioned conference.

The more immediate background to Bobbio’s book, in fact, was the 1994 general election in Italy, when the post-fascist party Alleanza Nazionale (National Alliance) became part of the first Berlusconi Cabinet, the first time since the fall of Fascism that a party on the far right spectrum had entered an Italian government; this was also the background to Umberto Eco’s overtly influential (in the US) Ur-Fascism article from 1995, as discussed here and here, though this context is mostly ignored in American commentary. In a way, then, this piece is a 30-year retrospective of the 1994-95 period; a 2024-25 edition, if you like.

Bobbio’s main objective in the book, I should say, was to argue for the relevancy of distinguishing between left- and right-wing ideas at a time in Italy when many commentators did not think it meaningful any longer; this was partly due to the post-war political arrangement in the country, with the Constitution outlawing fascist parties, the centrist and conservative Christian Democrats (Democrazia Cristiana) dominating politics and society for 50 years, and the Communist Party barred from any of the many coalitions formed during that time, despite the wide support it boasted. Bobbio strove to revive the debate around left and right ideologies by approaching the dichotomy in terms of how proponents of either the left or the right position themselves towards the issue of equality (or, rather, inequality), and it is this argument that I would like to revisit here. Read more »

A macchiato I had in Brixen, South Tyrol. Just thought I’d post a somewhat soothing photo.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.