by Eric J. Weiner

Many people familiar with Theodor Adorno and his work in sociology, philosophy, psychology, and cultural studies might not know about his work as a public intellectual in postwar Germany. For those readers who are not familiar with his legacy, this book is a perfect introduction to some of his most important ideas concerning free will, self-determination, and the persistence and influence of authoritarian structures in democratic and capitalistic systems. As a public intellectual, Adorno steps out of the shadow of academia and the Institute for Social Research. The lectures in this book, all delivered between 1949-1963, are not only accessible to lay readers but remain relevant to our world today. The insights he offers in reference to postwar German society are remarkably still applicable to 21st century neoliberal democratic societies. However different the 21st century is to the 20th, especially regarding technology and globalization, his analyses remain relevant to our current times. In some instances, they are even more relevant today than when he first delivered them.

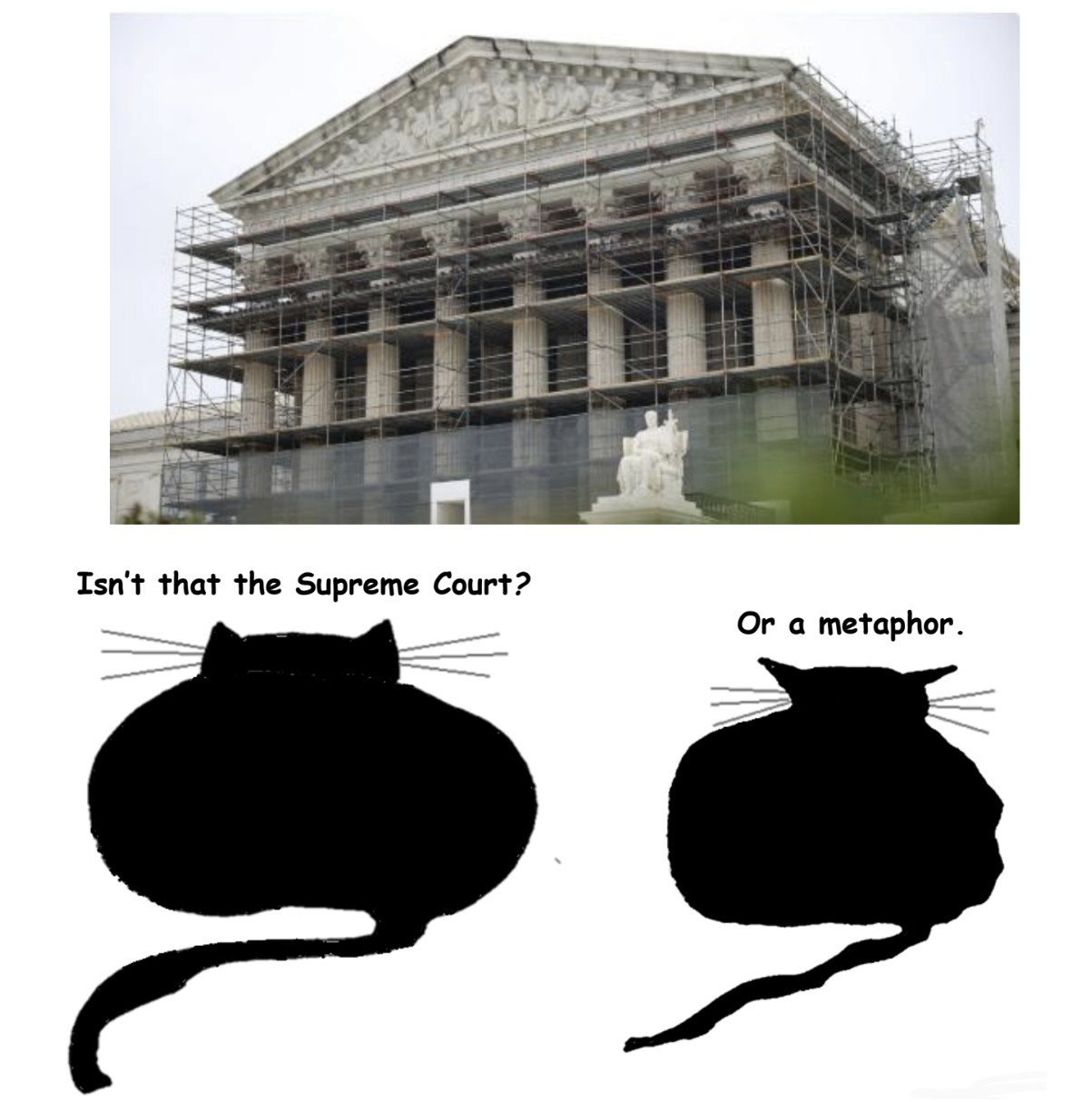

In 2025, as authoritarian discourses arise like ghosts from what might appear to be the cold ashes of 20th century fascism, Adorno’s work suggests that maybe they never really disappeared in the first place. From his perspective, what we are seeing in the United States and across the globe is a continuation of a hegemonic system of thought and behavior–and the consciousness that it engenders–that was never fully eradicated. Just as the “end of history” thesis was premature in announcing the triumph of western capitalism and democracy in the 1980s over communism, announcing victory over the ideology of authoritarianism and fascism in the west at the end of World War II is also beginning to look politically naïve and willfully ignorant.

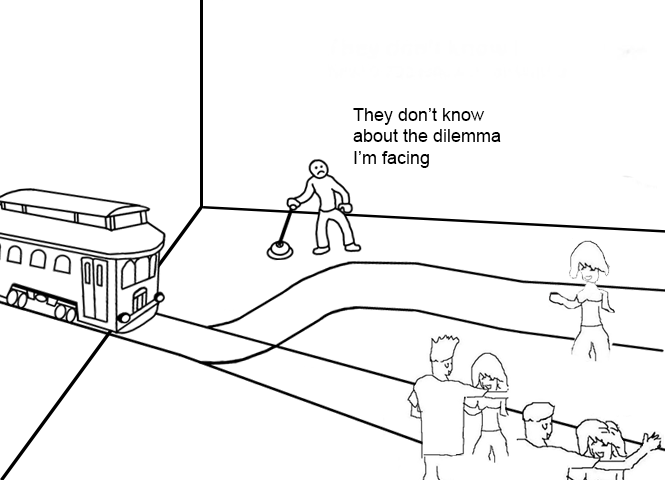

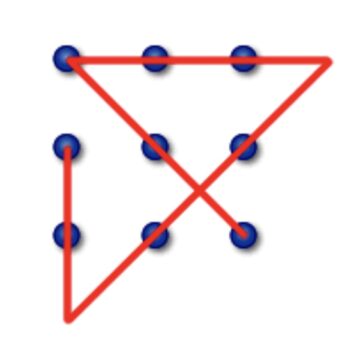

Defeating Hitler’s Third Reich militarily was not the same thing as extinguishing the ideas that fueled its popularity and fed its imperialistic and murderous imagination. Indeed, as the work of the Institute for Social Research consistently revealed, the proverbial rock from under which Hitler and Nazism crawled was made from a familiar and seemingly innocuous amalgam of science, philosophy, education, nationalism, and culture none of which, together or separately, gave away the unforeseen terror that was hiding in plain sight. From the time of Adorno’s public lectures to our current time, the task during these transitional periods of history is not to predict, like astrologists mapping the stars for clues about what the future holds. In these times, speculative social science, for Adorno, is no better than a crystal ball. Trying to guess at what will be at the expense of understanding and changing what is, is a fool’s goal. For Adorno, resistance to the rise of neo-fascist discourses in the postwar era is first and foremost to ask, “How these things will continue, and [taking] responsibility for how they will continue” (186). This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have a social imagination. But this is decidedly different than believing that we can actually know what the future holds. We should imagine what could be, as any tangible notion of educated hope depends on a vibrant social imagination, but we first must change, according to Adorno, our relationship to what is.

In what follows, I will discuss several points of entry from Adorno’s lectures into how and why right-wing extremism continues to thrive in the 21st century and the central role of education and culture in combatting or perpetuating these extremist ideologies. Read more »

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics.

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics. About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an

About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an  Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.

Why do we fight? That question has been asked by so many in the history of mankind: philosophers, psychologists, anthropologists, historians, sociologists, political theorists have come up over and over again with explanations as to why humans fight.

Why do we fight? That question has been asked by so many in the history of mankind: philosophers, psychologists, anthropologists, historians, sociologists, political theorists have come up over and over again with explanations as to why humans fight.