by Claire Chambers

Rebecca F. Kuang’s new novel Yellowface, a hilarious and haunting satire about the publishing industry, is proving a literary fiction bestseller this summer. However, it is her previous book Babel, or the Necessity of Violence that interests me here. Whereas Yellowface concerns contemporary America, Babel is a capacious piece of speculative fiction mostly set in Oxford during the 1830s. It was published in the Covid-19 pandemic under the young author’s abbreviated first name, and was a surprise hit due in part to its popularity on BookTok. As I will discuss, the novel deals with issues of language, translation, and colonialism in a startlingly original way.

Rebecca F. Kuang’s new novel Yellowface, a hilarious and haunting satire about the publishing industry, is proving a literary fiction bestseller this summer. However, it is her previous book Babel, or the Necessity of Violence that interests me here. Whereas Yellowface concerns contemporary America, Babel is a capacious piece of speculative fiction mostly set in Oxford during the 1830s. It was published in the Covid-19 pandemic under the young author’s abbreviated first name, and was a surprise hit due in part to its popularity on BookTok. As I will discuss, the novel deals with issues of language, translation, and colonialism in a startlingly original way.

Protagonist Robin Swift had been born in Canton and given a Chinese name that is never disclosed. After his mother’s death in the so-called Asiatic Cholera pandemic of the late 1820s, a professor called Richard Lovell becomes his guardian for reasons initially unknown. Lovell allows the boy to choose his own name (he decides on ‘Robin’ for the bird, and ‘Swift’ from Gulliver’s Travels) before bringing him to England.

Lovell prepares Robin for admission at the prestigious Royal Institute of Translation at Oxford, known to students as Babel. Compared with the classist and white supremacist patriarchy of the rest of Oxford University in that period at least, Babel is multilingual, multicultural, and even admits girls. Here Robin makes three friends: Ramy from Calcutta, Haitian Victoire, and the English rose Letty. In the institute’s intensive language programme, the teenagers’ friendship too quickly becomes intense. Ramy, Victoire, and Robin still feel a complex loyalty to the (quasi-)colonized homelands they had to leave behind. Cracks start to emerge in their relationship with Letty, who holds sympathy for the British civilizing mission. Read more »

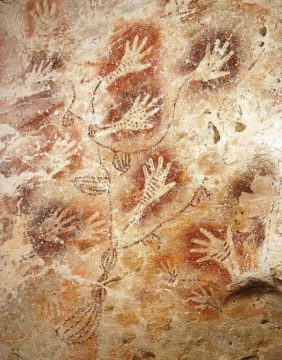

First mixing the grounds of red and yellow ocher with water so as to make a viscus, sticky gum which she puts between her cheek and whatever teeth she may have had, the woman placed her rough, calloused, weather-beaten, sun-chapped hand against the nubbly surface of the limestone cave’s wall, and then perhaps using a hollow-reed picked from the silty banks of the Rammang-rammang River she would blow that inky substance through her straw, leaving the shadow of a perfect outline. This happened around forty thousand years ago and her hand is still there. A little over two dozen of these tracings in white and red are all over the cave wall. What she looked like, where she was born, whether she had a partner or children, what gods she prayed to and what she requested will forever be unknown, but her fingers are slim and tapered and impossible to distinguish from those of any modern human. “It may seem something of a gamble to try to get close to the thought processes that guided these people,” writes archeologist Jean Clottes in What is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity. “They are so remote from us.” Today a ladder must be pushed against the surface of the cave’s exterior, which appears as if a dark mouth over the humid, muddy Indonesian rice fields of South Sulawesi Island, so as to climb inside and examine her compositions, but during the Neolithic perhaps they simply cleaved alongside the rock face with their hands and feet. Several other paintings are in the complex; among the earliest figurative compositions ever rendered, some of the sleek, aquiline, red hog deer, others of chimerical therianthropes that are part human and part animal. Beautiful, obviously, and evocative, enigmatic, enchanting, but those handprints are mysterious and moving in a different way, a tangible statement of identity, of a woman who despite the enormity of all of that which we can never understand about her, still made this piece forty millennia ago that let us know she was here, that she lived.

First mixing the grounds of red and yellow ocher with water so as to make a viscus, sticky gum which she puts between her cheek and whatever teeth she may have had, the woman placed her rough, calloused, weather-beaten, sun-chapped hand against the nubbly surface of the limestone cave’s wall, and then perhaps using a hollow-reed picked from the silty banks of the Rammang-rammang River she would blow that inky substance through her straw, leaving the shadow of a perfect outline. This happened around forty thousand years ago and her hand is still there. A little over two dozen of these tracings in white and red are all over the cave wall. What she looked like, where she was born, whether she had a partner or children, what gods she prayed to and what she requested will forever be unknown, but her fingers are slim and tapered and impossible to distinguish from those of any modern human. “It may seem something of a gamble to try to get close to the thought processes that guided these people,” writes archeologist Jean Clottes in What is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity. “They are so remote from us.” Today a ladder must be pushed against the surface of the cave’s exterior, which appears as if a dark mouth over the humid, muddy Indonesian rice fields of South Sulawesi Island, so as to climb inside and examine her compositions, but during the Neolithic perhaps they simply cleaved alongside the rock face with their hands and feet. Several other paintings are in the complex; among the earliest figurative compositions ever rendered, some of the sleek, aquiline, red hog deer, others of chimerical therianthropes that are part human and part animal. Beautiful, obviously, and evocative, enigmatic, enchanting, but those handprints are mysterious and moving in a different way, a tangible statement of identity, of a woman who despite the enormity of all of that which we can never understand about her, still made this piece forty millennia ago that let us know she was here, that she lived.

How much you can divide this sentence into similarly incorrect phrases?

How much you can divide this sentence into similarly incorrect phrases?

I have a confession to make: I ❤️ Seymour Glass. If you don’t know who that is, count yourself lucky and walk away now—come back in a few weeks when I’ll be discussing humiliating experiences at middle-school dances or whatever. (Obviously I am joking—as always, I desperately want you to finish reading this essay.)

I have a confession to make: I ❤️ Seymour Glass. If you don’t know who that is, count yourself lucky and walk away now—come back in a few weeks when I’ll be discussing humiliating experiences at middle-school dances or whatever. (Obviously I am joking—as always, I desperately want you to finish reading this essay.)

I’ve mostly escaped the selfie photo culture, not out of some virtuous modesty, but because I generally look like a confused mouth-breathing moron in photos. So selfies are more of an indictment for me than something I want to post on Instagram. If I photographed like a Benicio del Toro or George Clooney, all bets would be off. And before I offend and get canceled by any mouth breathers, I am part of the mouth-breathing family due to a deviated septum. At full rest, I sound like one of those artificial lungs in hospitals.

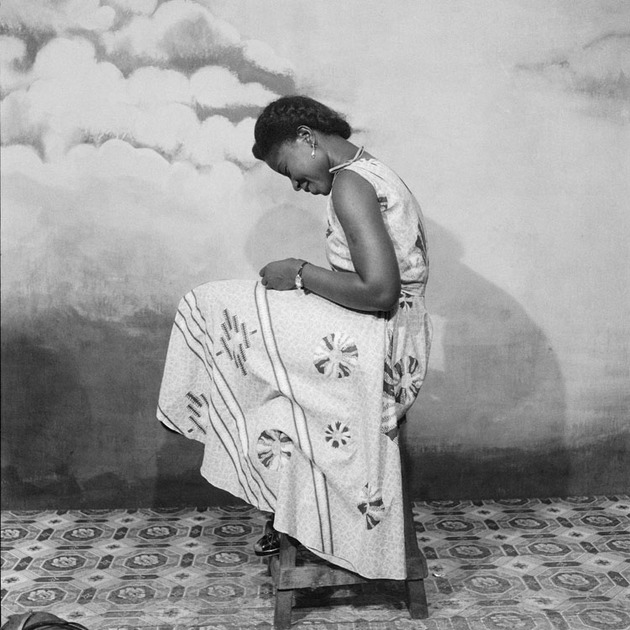

I’ve mostly escaped the selfie photo culture, not out of some virtuous modesty, but because I generally look like a confused mouth-breathing moron in photos. So selfies are more of an indictment for me than something I want to post on Instagram. If I photographed like a Benicio del Toro or George Clooney, all bets would be off. And before I offend and get canceled by any mouth breathers, I am part of the mouth-breathing family due to a deviated septum. At full rest, I sound like one of those artificial lungs in hospitals. James Barnor. Portrait, Accra, ca 1954.

James Barnor. Portrait, Accra, ca 1954. Panic about runaway artificial super-intelligence spiked recently, with doomsayers like

Panic about runaway artificial super-intelligence spiked recently, with doomsayers like

Not long ago, I went to the Yale University Art Gallery and saw their collection of Egyptian art. Seeing the dates on some of the pieces, it occurred to me that I had never really considered just how old Egyptian civilization is. I looked up some historical events to get perspective, and learned that I am closer in time to the assassination of Julius Caesar (44 BCE, which is 2,066 years ago) than Julius Caesar was to the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza (circa 2500 BCE, over 2,400 years before Caesar’s death). Caesar’s death is ancient history, and the building of the Great Pyramid is also ancient history, but – for the sake of perspective here – the Great Pyramid’s construction was also ancient for Julius Caesar. That’s how old Egyptian civilization is.

Not long ago, I went to the Yale University Art Gallery and saw their collection of Egyptian art. Seeing the dates on some of the pieces, it occurred to me that I had never really considered just how old Egyptian civilization is. I looked up some historical events to get perspective, and learned that I am closer in time to the assassination of Julius Caesar (44 BCE, which is 2,066 years ago) than Julius Caesar was to the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza (circa 2500 BCE, over 2,400 years before Caesar’s death). Caesar’s death is ancient history, and the building of the Great Pyramid is also ancient history, but – for the sake of perspective here – the Great Pyramid’s construction was also ancient for Julius Caesar. That’s how old Egyptian civilization is.

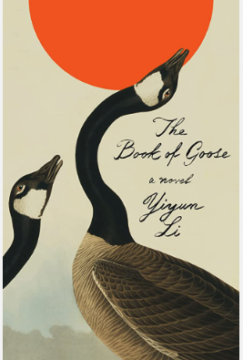

When Yiyun Li took questions about her new novel, The Book of Goose, at my local bookstore, someone said her new novel felt awfully dark. (I don’t remember the precise wording, though Yiyun might, as she sometimes offers people she has met briefly “a detailed account” of their encounter

When Yiyun Li took questions about her new novel, The Book of Goose, at my local bookstore, someone said her new novel felt awfully dark. (I don’t remember the precise wording, though Yiyun might, as she sometimes offers people she has met briefly “a detailed account” of their encounter  Twenty-six years ago, on a late-afternoon, late-summer sojourn down Liverpool’s Bold Street, a High Street of dark pubs and record stores, Donner kebab counters and chip shops, Frank accidentally walked into 1965. On his idyl perambulations to meet up with his wife at Waterstone’s, where she was grabbing a copy of Trainspotting, and Frank noticed a different slant of light, an alteration in the atmosphere, a variation in the sounds from the street, a drop in temperature. The summer odor of warm beer and fetid air replaced with the crispness of Christmas time. Approaching the bookstore, the Cranberries blaring on the music system, and mid-tune it’s replaced with a tinny radio playing a Herman’s Hermits number. Bold Street’s pedestrians were no longer wearing Oasis and Blur t-shirts, now they were men in boating jackets and mop tops, women in Halston dresses and pixie cuts. The road no longer paved, but cobblestoned. Frank noted that the Waterstone’s façade was now of a shop named “Cripps,” a woman’s clothing store that had been on this spot but closed decades before. Just as he crossed the threshold, and Cripps was abruptly transformed back into a bookstore. Misapprehension, misconception, misinterpretation? Hallucination or hoax? Vortex or ghosts? As paranormal writer Rodney Davies helpfully opines in Time Slips: Journeys into the Past and Future, “One theory state that past, present, and future are all one… But our limited consciousness can only experience time by being in what we know as ‘the present.’” Mayhap.

Twenty-six years ago, on a late-afternoon, late-summer sojourn down Liverpool’s Bold Street, a High Street of dark pubs and record stores, Donner kebab counters and chip shops, Frank accidentally walked into 1965. On his idyl perambulations to meet up with his wife at Waterstone’s, where she was grabbing a copy of Trainspotting, and Frank noticed a different slant of light, an alteration in the atmosphere, a variation in the sounds from the street, a drop in temperature. The summer odor of warm beer and fetid air replaced with the crispness of Christmas time. Approaching the bookstore, the Cranberries blaring on the music system, and mid-tune it’s replaced with a tinny radio playing a Herman’s Hermits number. Bold Street’s pedestrians were no longer wearing Oasis and Blur t-shirts, now they were men in boating jackets and mop tops, women in Halston dresses and pixie cuts. The road no longer paved, but cobblestoned. Frank noted that the Waterstone’s façade was now of a shop named “Cripps,” a woman’s clothing store that had been on this spot but closed decades before. Just as he crossed the threshold, and Cripps was abruptly transformed back into a bookstore. Misapprehension, misconception, misinterpretation? Hallucination or hoax? Vortex or ghosts? As paranormal writer Rodney Davies helpfully opines in Time Slips: Journeys into the Past and Future, “One theory state that past, present, and future are all one… But our limited consciousness can only experience time by being in what we know as ‘the present.’” Mayhap.