by Muna Nassir

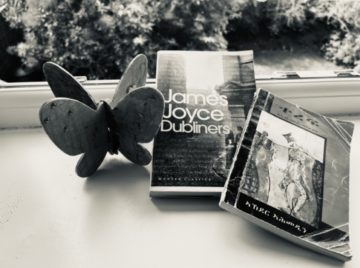

Sitting on the sill, head slightly resting on the pane, The Dubliners in hand, I look out the window, much like the eponymous Eveline, at the start of this particular short story. The darkness, in this case, is ready to invade not an avenue with concrete pavement and rows of redbrick terraced houses in Dublin, but an empty playground with bright coloured slides, swings, seesaws, and a roundabout in South Manchester. My vantage point allows me an eye level view of the giant oak sitting at the closest corner of the park, across the street. Unlike the slanted view from the living room, here, I can almost see the tiniest ferns sprouting on its bark. The oak’s tip points towards the sky with its thick branches spread out like the arms of a dervish in a trance. Bearing the weight of the subject in mind, I sigh in, inhaling the evening breeze. My nostrils detect not the smell of dusty cretonne but rather the scent of fallen leaves imbued with the myriad hues of autumn. From green to lime, to orange, red, maroon, and brown. The tree sits on a sideway, a space that seems to have been added as an afterthought, giving the park an irregular shape. Basking in another worldly silence, the oak exudes a stillness befitting the day’s retirement for the night.

At the opening of this very short story, Eveline, who is just over nineteen, is presented as rather wearied. We read in the opening lines, ‘she was tired’. Torn between the dread and drudgery of life at home with her abusive father on the one hand and the prospect of a new life in Buenos Aires as Frank’s wife, a man she scarcely knows and hardly loves on the other— she finds herself at a forking path. The first mention of her father paints him often hunting, Eveline and her siblings as small children, in from their playtimes in the avenue, ‘with a blackthorn stick’. She looks out the window into the evening, reminiscing, as she weighs both her options. She reviews the familiar objects in her home, ‘from which she had never dreamed of being divided’ and the possibility that she might never see them again registers her dilemma for the first time. In the next paragraph, she asks herself if consenting to go away to begin with was even wise. From the names of the families in the neighbourhood, to descriptions of the streets, the language from the outset, in true Joycean style, is specific and local to Ireland. ‘The children of the Avenue used to play together in that field — the Devines, the Waters, the Dunns, little Keogh the cripple.’ In this short story Joyce, who is known to have said, ‘in the particular is contained the universal’ explores universal sentiments and emotions — the tug and pull of the comfort if not the security of the familiar, juxtaposed with the fear and the alluring potential of the unknown —that arise when one is standing in between two divergent roads in one’s life.

This short story takes me back to a starlit evening in Asmara’s Embasoira Hotel on a mild evening in May 2014. A book launch. The chairs decked with white satin covers and bow ties laid out in the main hall. I sit at the back. The guest speakers take turns to laud the young writer and his literary career spanning over fifteen years. I stand in a long queue and when my turn comes the writer, Akhedr Ahmedin, signs my copy of his debut collection of short stories The Remnant with the words, ‘thank you for coming today. I hope we will get a chance to debate and share our ideas of writing soon’. We never got the chance to do that. I left the country not long afterwards and Akhedr a few years later. He currently lives in Kenya with his family and works as a journalist for BBC Tigrinya.

Much like Eveline the unnamed soldier in Akhedr Ahmedin’s, short story The Remnant, which is also the title of the collection, finds himself in a liminal space both physically and in his mind. The setting, where the soldier’s squad is garrisoned, is an almost entirely evacuated village, in the aftermath of a war. It has been two years since the start of the 1998 border war between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Both countries, in spite of the recent peace deal, are caught in between war and peace. It is uncertain times. Yet, there is hope that it would soon be time for the soldiers to return home and thus, the first sentence opens with the soldier wondering how much he must have changed and if he would be able to take anything with him for his mother. He is clearly traumatised. ‘I could not bear the wound in my soul, the war spared nothing and no one’.

The soldier further describes the horrors he endured. ‘Having witnessed youth destroyed, humanity buried, love shattered, and dreams thwarted, every fabric in my being is pierced through and through, threadbare.’ However, he seems to have found the answer for the latter part of his question in the opening sentence — in a young woman of great beauty he sees walking back from his post as a night sentinel. The first time he sees her, ‘the lazy sun’ is resting its rays on her face. He is taken by the beauty in her eyes, the long hair, half plaited half resting on her shoulders, and her traditional chiffon long dress. The soldier marvels at how hard it had become to keep his eyes away from her and wonders, if in giving her his love, his soul would finally heal. Smitten, he starts to contemplate how — the absurdity of war which he struggled to make sense of, if waged in defence of the beautiful instead of a piece of land —would begin to feel justified. In the days that follow, the young soldier is torn between divulging his feelings to his beloved— fantasising incessantly about the details of their soon to come shared love life— and keeping the thoughts to himself.

In these short stories, both writers, Akhedr and Joyce, remain removed and impartial. They present the main characters’ thoughts as they occur in the main characters’ minds. Unlike in Eveline, however, in The Remnant the reader is inside the soldier’s and not the young woman’s mind. The narrative follows his train of thought while the beautiful woman’s interiority remains inaccessible. Observed and looked at only from the outside, her silence in the short story both in speech and thought, looms heavy. Meanwhile, Eveline, still looks out the window, oscillating between the merits of staying at home and the tempting prospects of her married life with Frank. She asks herself, ‘what would they say of her in the Stores [her place of work] when they found out that she had run away with a fellow?’ She flits through her memories of what she considers happy at home but remembering how on edge Miss Gavan at work is towards her, Eveline, like a boat rocked by heavy storms, tilts to the other side. Like the young soldier she begins to fantasise, how ‘people would treat her with respect’, once she is married to Frank and how ‘she would not be treated as her mother had been’. She then remembers her father’s intemperance and mistreatment and almost concludes, hers was a hard life. Yet standing at that point in her life where she is just about to put the past behind her, and start afresh, Eveline realises, ‘she did not find it a wholly undesirable life’.

A white butterfly flutters into the room through the tilted opening of the window at the top and steals my attention. The evening is still lingering, painting the park across the road in the golden hue of twilight. The butterfly moves across the room, landing briefly on the double bed in the middle and then continuing to flutter towards the white chest of drawers at the opposite end. It comes back to the window and attempts to find the opening again, crushing softly against the cold glass, a few times. Torn between the desire to scoop the butterfly in my hands to release it and the hope that it would somehow find its own way out, I sit still. In its imprisonment the butterfly reminds me of the exiled self, mentally existing elsewhere while the body is in the here and now. As though straddling two lanes at once. A sort of a Frankenstein, with the different parts patched in random patterns— a far cry from the hybridised homogeneous self that some like to fantasise about. Sometimes walking down the streets the serene curves of an absent-minded smile form on my face. The trigger would not be from the here and now but somewhere distant, perhaps the tender memory of the sassiness in the octogenarian neighbour, Adey Brchiqo’s voice, as she mixes people’s gender in her speech or the memory of my grandmother’s blunt loving replies. A citizen of neither the here nor the there but that of the muted space in between.

While Eveline oscillates, rocking back and forth between thoughts of staying and leaving, the soldier in The Remnant, lives his days and nights for a glimpse of his beloved, which further fuels his fantasies. His squad leader reprimands him for his shortening temper, and he is regarded with suspicion. The besotted soldier, eventually, risking punishment for mutiny stays behind and diverts to his beloved’s house. She is sat outside and as he gets close, he finds only a shell of the beauty he had discerned from afar. ‘When you get close you only see the outline of her beauty, she looks disheveled, her body parched and her skin grimed.’ He tries to strike a conversation. He is met with a deep silence. Her mother comes out to the threshold and tells him that her daughter is ‘a remnant of those butchered and traumatised by war’. And that she has been mute, ever since the sexual assault she suffered at the hands of the invading soldiers. There is an unbridgeable pause. The mother adds, that is, ‘save the primordial cry she let out when it was happening’. She further adds, ‘my son, do you have a cure for a torn woman?’

The darkness has deepened in the avenue. A reminder that very little time had elapsed from the opening scene. Eveline is still standing by the window, holding two letters in white envelopes for her father and her brother. She remembers the nice things her father did for her growing up, albeit very few and far in between, and soon hears a street organ, which takes her back to the promises she made her mother the evening she died. To look after her two younger siblings and to keep the family intact. She remembers her mother’s life, which she calls, ‘a life of common place sacrifices’. And the gibberish, ‘Derevaun Seraun!’, that her mother repeats with ‘foolish insistence’ on her deathbed, eventually, compels Eveline to leave. The next we see of her; she is at the station with Frank. The boat that would transport her into this future which Eveline, hopes would be filled with life if not love, is described as a black mass. In the final scene, she is in an emotional turmoil, ‘all the seas of the world tumbled about her heart’. Just before she is about to embark the boat, Eveline, who had been silent until this point in the story (whilst Miss Gavin scolded, her father cursed, and Frank sang) sends ‘a cry of anguish’.

Perhaps the magnitude and type of trauma the two characters endure are not suitable for comparison, but this is not so much about comparing the different types of trauma as it is about an attempt to analyse and understand writing difficult female experiences through the lens and work of male writers. Having reached the delicate point where language buckles under the full weight of the oppressive trauma, both writers instinctively give in to an utterance that predates language itself. A primordial cry of anguish. Language comes unbound, unfettered, fluid, and not dissimilar in manner to what Cixous calls écriture féminine. At this point, both Akhedr and Joyce, rightly refrain from lending their voices to both the unnamed young woman and Eveline respectively. Both female characters are protected by an impenetrable silence, beyond the reach of phallocratic male writing. After the release of the cry, there is a return to a sort of a childlike state that seems to precede notions of the self and identity. In the final sentences, Joyce writes of Eveline, ‘she set her white face to him, passive, like a helpless animal. Her eyes gave him no sign of love or farewell or recognition.’ Likewise, after the assault and the cry that follows, the young woman in The Remnant, is hurled into a catatonic state from which she never mentally returns. Akhedr describes her mother cry out, ‘my poor daughter, I don’t know what’s overtaken her after that last cry.’

I stand looking out the window. My nostrils do not catch the smell of dusty cretonne but the cool breeze of an autumn night. The flight of a part of the self to an unknown space beyond any reach, that comes with the release of an anguished cry, in both short stories, brings an idea of the release of the suppressed feminine self to my mind. A final act of defiance. I think of silences and in-between spaces. Imperceptible, like the line separating memory from fantasy. Fleeting and subtle, like the pause between two utterances. I think of the last step at a forking path, the last grounding tip before the leap. I scoop the white butterfly in my hands and release it into the park that is now in total darkness. I breath out.